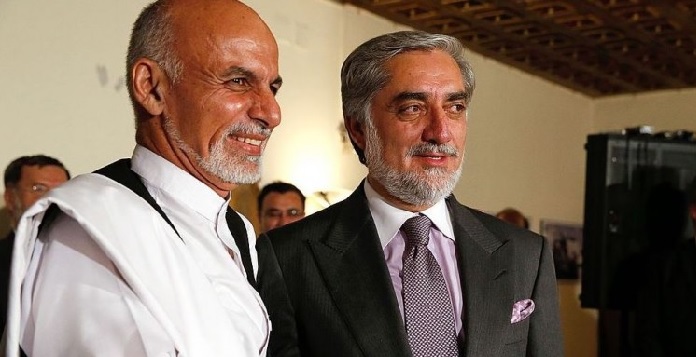

Rival Afghan leaders strike a power-sharing deal, but there are plenty of other obstacles on the road to peace

There was no other way to end the political logjam in conflict-ridden Afghanistan than to make current President Ashraf Ghani and the outgoing Chief Executive Abdullah Abdullah agree to share power. Only an ascendant Afghan Taliban stood to benefit from the continued political impasse and the resulting weakening of government institutions.

Despite widespread skepticism regarding its performance on governance and security, the Kabul government still controls a substantial chunk of Afghan territory and provides education, health care, and other basic services for the majority of Afghan citizens. Its security forces have been working diligently with the United States and other international partners to prevent al-Qaeda and ISIS from expanding their presence in the country.

The power-sharing agreement announced on May 17 has been widely welcomed by the international community because the political tensions between the two rivals were viewed as one of the major hurdles to the advancement of an intra-Afghan reconciliation process following the signing of an historic peace deal between the U.S. and the Taliban in Doha in late February. The political jockeying in Kabul is far from the only impediment to reconciliation though, and the Taliban’s unwillingness to sit down with any Afghan government delegation and the breakdown of talks on prisoner exchanges suggest there are deeper obstacles to the peace process. Despite the impact of the coronavirus pandemic, the Taliban has given no sign that it plans to scale back or end its attacks, and indeed it derives its bargaining power from its capacity for violence.

Not the first time either

The power-sharing deal between Ghani and Abdullah brings to a close the long-running dispute over the results of the September 2019 elections, but this is not the first time that Afghanistan has faced political uncertainty due to a contested presidential election. A similar power-sharing arrangement was brokered by the Obama administration following a disputed election in 2014, as a result of which Abdullah became the country’s chief executive, a role with similar powers to a prime minister, under a Ghani-led government. The relationship between the two men remained fraught, however, and Ghani and Abdullah often clashed on important political issues. The 2019 presidential elections were once again marred by allegations of large-scale fraud and irregularities. Both Ghani and Abdullah declared themselves president and held their own inaugurations, overshadowing the peace deal signed in Doha.

The U.S. has been the main international backer of the Afghan government, the only institutional partner which over the years has helped Washington reverse the dangerous drift of the country in the direction of Taliban-Pakistan dominance. Thus, the Americans were not oblivious to the divisions within the Afghan government and made repeated efforts to broker peace between the two rivals. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo made an unscheduled trip to Kabul in March to try to resolve the political impasse, but he failed to get the two antagonists to agree to a deal. He severely criticized both men for their intransigence, which he said had “harmed U.S.-Afghan relations and, sadly, dishonors those Afghan, American, and coalition partners who have sacrificed their lives and treasure.” He also announced that the Trump administration would cut $1 billion in aid to Afghanistan.

The terms of the deal

But the two sides eventually came around. This may have been motivated by President Donald Trump’s determination to withdraw U.S. forces from Afghanistan regardless of the outcome of the intra-Afghan political process or efforts to convince the Taliban to rein in its attacks. Both men are aware that Trump views Afghanistan as a quagmire from which an exit is the best course of action. The prospect of a substantial reduction in American financial assistance likely played a role as well.

Under the terms of the power-sharing deal, as announced by Presidential Spokesman Sediq Sediqqi, both Ghani and Abdullah will have an equal share in the government and Abdullah “will lead the National Reconciliation High Council and members of his team will be included in the cabinet.” In effect, Abdullah has been tasked with leading a broader Afghan team representing political leaders, women, and civil society members to talk to the Taliban to bring the four decades of war to a close. But a political agreement alone will not be sufficient to end the entrenched mistrust between the two camps, and it remains to be seen how Ghani and Abdullah will build a genuine partnership to navigate a fragile peace process. Nevertheless, Abdullah’s first priority must be to resolve the disagreement over the release of prisoners, which the Taliban insists is a prerequisite for an intra-Afghan dialogue. If not swiftly addressed, the issue could snowball into a bigger crisis, leading to increased violence and threatening the gains made in the power-sharing deal.

Abdullah has impressive credentials to lead the effort and has served in government under both former President Hamid Karzai and Ghani, including as foreign minister. He has proved his popularity among Afghans in two bitterly-contested presidential elections and his supporters say his mixed Pashtun and Tajik heritage makes him a figure that could unite Afghans beyond narrow ethnic divisions. He is a seasoned politician who knows that his long association with the mujahideen movement gives him an authentic conservative Afghan image, while his seemingly modern appearance also allows him to reach out to the non-Pashtun middle class. However, it will be difficult for Pashtuns to shed their long-held suspicions about Abdullah, who despite his mixed ancestry, is seen by a majority of Pashtuns as Tajik. His close association with Ahmed Shah Masood is also problematic at a time when the Pashtun-dominated Taliban is forcibly seeking integration into Afghan political structures. However, the most important factor in determining the success or failure of Abdullah’s attempt to position himself as the architect of Afghan peace is how he will be perceived by Pakistan’s security establishment, which has a primary role in any Afghan peace process.

The power-sharing agreement has not been without controversy either, especially in regards to former Vice-President Abdul Rashid Dostum, who has been an important part of Abdullah’s team and served as his running mate in the 2019 elections. Despite accusations of involvement in the rape and torture of a political rival, Dostum will now be designated as a marshal of the Afghan armed forces. Although there have been countless allegations of his involvement in war crimes and human rights abuses, this is perhaps a pragmatic recognition of Dostum’s political clout among the ethnic Uzbek community. Dostum’s appointment is also a disturbing sign that Ghani and Abdullah may be inclined to grant political concessions to the Taliban even at the expense of civil rights.

The US-Taliban deal and the recent rise in violence

Peace processes have always been complicated and messy affairs in conflict-ridden political systems, and Afghanistan is no exception. While the agreement between Ghani and Abdullah will help to address one of the major challenges facing the country, it is far from the only one, as the rising level of violence and the shortcomings of the U.S.-Taliban deal have recently made clear. Moreover, the U.S.-Taliban deal is not an end in itself, and it is meant to promote intra-Afghan peace between the Afghan government and the Taliban. The deal is also seen as a way to enlist the Taliban in the fight against ISIS, which the U.S. has for some time considered a greater threat to U.S. security interests than the Taliban itself. One of the key provisions is an American commitment to reduce its military footprint in Afghanistan to 8,600 troops by mid-July. In return, the Taliban has promised not to allow al-Qaeda and other terror groups to use Afghan soil to threaten the U.S. and its allies. However, those who believed that the U.S.-Taliban deal would pave the way for a significant reduction in violence must be disappointed. Instead, the Taliban has only ramped up its attacks on Afghan security forces, and the group has not given up on its long-held view that military force is necessary to build a new political consensus.

As reported by the UN, more than 500 civilians were killed in the first quarter of 2020, and violence has continued unabated since. On May 12, Kabul was rocked by a terror attack in which 24 people, including two newborn babies, were killed at a maternity ward run by Médecins Sans Frontières. This sickening attack remains a grim reminder of the consequences of the endless war in Afghanistan. On the same day, a suicide bombing targeting a funeral in Nangarhar Province killed more than 30 people. The Taliban denied responsibility for both attacks. On May 18, a car-bomb attack on an intelligence base in eastern Afghanistan killed another five people. Although Washington insisted that the ISIS was behind the maternity hospital attack, Ghani chose to differ. The Kabul government has been particularly outraged by ongoing Taliban attacks against Afghan military personnel and bases, and following the latest surge in violence, it decided to resume offensive operations against the Taliban and other terror groups. But Ghani’s military campaign is likely to see only limited success.

The continuation of terrorist violence is also a reminder of some inherent contradictions and problems with the U.S.-Taliban deal. Critics of the Trump administration are unanimous in their view that the deal has squandered almost all the leverage that the U.S. had in exchange for mere platitudes. U.S. Special Representative Zalmay Khalilzad, the architect of the deal, has himself acknowledged on May 15 that the U.S.-Taliban pact does not prevent the Taliban from engaging in attacks against Afghans. According to him, “The agreement does not specifically mention for them [Taliban] not to attack Afghan forces,” but the Taliban has agreed that a cease-fire “would be one of the first subjects when intra-Afghan negotiations begin.” He added that the U.S. believes “that they [Taliban] are violating the spirit if not the letter” of the deal. A week earlier, Khalilzad, in a meeting with the Taliban deputy leader Mullah Baradar in Doha, had demanded progress on a number of issues, including a “humanitarian cease-fire” so that America’s deal with the Taliban could be operationalized.

The increasing chaos in Afghanistan has assumed alarming proportions, while eclipsing any prospects of a breakthrough. Further delays in the intra-Afghan peace process would not only damage U.S. national interests but also endanger regional security. However, with Ghani and Abdullah now agreeing to set aside their political differences, the start of the intra-Afghan dialogue is at least one step closer. In the current atmosphere of pessimism and skepticism, one can hardly be enthusiastic about the prospects for the peace process as concerns abound about the continuing violence, but it is precisely for this reason that Abdullah and his negotiating team will have to find a modus vivendi with the Taliban. The exercise should not be guided by short-term political considerations and personal egos; it should instead aim to defeat the machinations of spoilers while showing readiness to shift the goalposts in a spirit of give and take.