Lessons from the Collapse of Afghanistan’s Security Forces

Abstract: Six themes emerge from a close examination of the Afghan National Defense and Security Forces’ (ANDSF) collapse in 2021: the ANDSF collapse was months—if not years—in the making; the United States did not give the ANDSF everything they needed to be independently successful; the ANDSF did put up a fierce fight in many areas; the ANDSF were poorly served by Afghan political leaders; the ANDSF were poorly served by their own commanders; and the Taliban strategy overwhelmed and demoralized the ANDSF. From these themes, there are three key lessons: the ANDSF’s failure had many fathers; the U.S. model of security assistance requires reform; and greater emphasis on non-material factors (e.g., morale) is needed in future security force assessments.

On August 15, 2021, Afghanistan’s President Ashraf Ghani boarded an aircraft bound for Tajikistan, effectively abdicating his position as the country’s president and cementing the Taliban’s victory over his Western-backed government.1 The preceding four months, between President Joe Biden’s announcement on April 14 that the United States would withdraw all of its military forces from Afghanistan2 and Ghani’s flight from the country, saw the Taliban conduct a nationwide campaign that quickly overwhelmed the country’s security forces and forced their total collapse.

Since August 15, the United States—and indeed, the world—has tried to understand what happened in Afghanistan that led to this stunning turn of events. A plethora of forensic articles have already been published by news agencies and analysts,3 and U.S. government officials up to and including President Biden have offered explanations as well.4 From these initial offerings, three thematic narratives have emerged that are specific to the Afghan National Defense and Security Forces (ANDSF). The first is that Afghanistan’s army—and therefore, the country—collapsed in less than two weeks. The most cogent rendering of this theme came in a remark from Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Mark Milley, who said, “There was nothing that I or anyone else saw that indicated a collapse of this army, and this government, in 11 days.”5

The second is that the United States and its international partners gave the ANDSF everything they needed to be independently successful.6 And the third is that these forces simply did not fight.7 The most significant advancement of the second and third themes came from President Biden, who has remarked on them several times. For example, in his August 16 speech to the nation, he stated:

American troops cannot and should not be fighting in a war and dying in a war that Afghan forces are not willing to fight for themselves. We spent over a trillion dollars. We trained and equipped an Afghan military force of some 300,000 strong … a force larger in size than the militaries of many of our NATO allies. We gave them every tool they could need. We paid their salaries, provided for the maintenance of their air force … We provided close air support. We gave them every chance to determine their own future. What we could not provide them was the will to fight for that future.8

But are these themes accurate? And do they represent the primary takeaways from the events that unfolded in Afghanistan over the summer of 2021? In this article, the author will argue that these themes are incorrect—or at least, significantly incomplete. The article will present this case by first providing a reconstruction of events in Afghanistan from mid-April to mid-August 2021. The author will then identify a more complete and accurate set of key themes that flow from these events. And those themes will be used to offer a more salient set of lessons from the collapse of Afghanistan’s security forces.

The author offers this article fully acknowledging that even though he was heavily critical of the ANDSF’s capabilities for many years9 and had called for significant reforms to address the issues he identified,10 he was still one of many analysts who assessed that these forces would fare better on their own against the Taliban than they ultimately did. Indeed, he tweeted on August 12:

I am legitimately shocked at how quickly the cities of #Afghanistan have fallen. I knew the #ANDSF weren’t as strong as advertised in rural areas, but I genuinely believed they’d stand & fight to defend the cities. I was wrong.11

If lessons are to be learned from events as they unfolded in Afghanistan, it is imperative for all to revisit the details of what happened and why—and to use the understanding gained through historical analysis to identify what about the approaches and assessments were wrong. This article was written in that spirit and is an attempt to spark a broader conversation along these lines.

Before proceeding, a caveat: It is still too early to have definitive and comprehensive accounts of what happened in Afghanistan this past summer. For example, there is very little reporting from Taliban sources regarding the logic and extent of their actions, and accounts of the political dealings among Afghan elites and between them and Taliban interlocutors are missing. In addition, many Western sources uncritically promulgated the themes advanced by Western officials in real time (e.g., that the ANDSF collapsed in 11 days). As such, the author will primarily rely here on reporting from Afghan news sources, reputable Afghan journalists, and Western journalists and analysts who were based in Afghanistan.

Recap of the Collapse

Early 2021

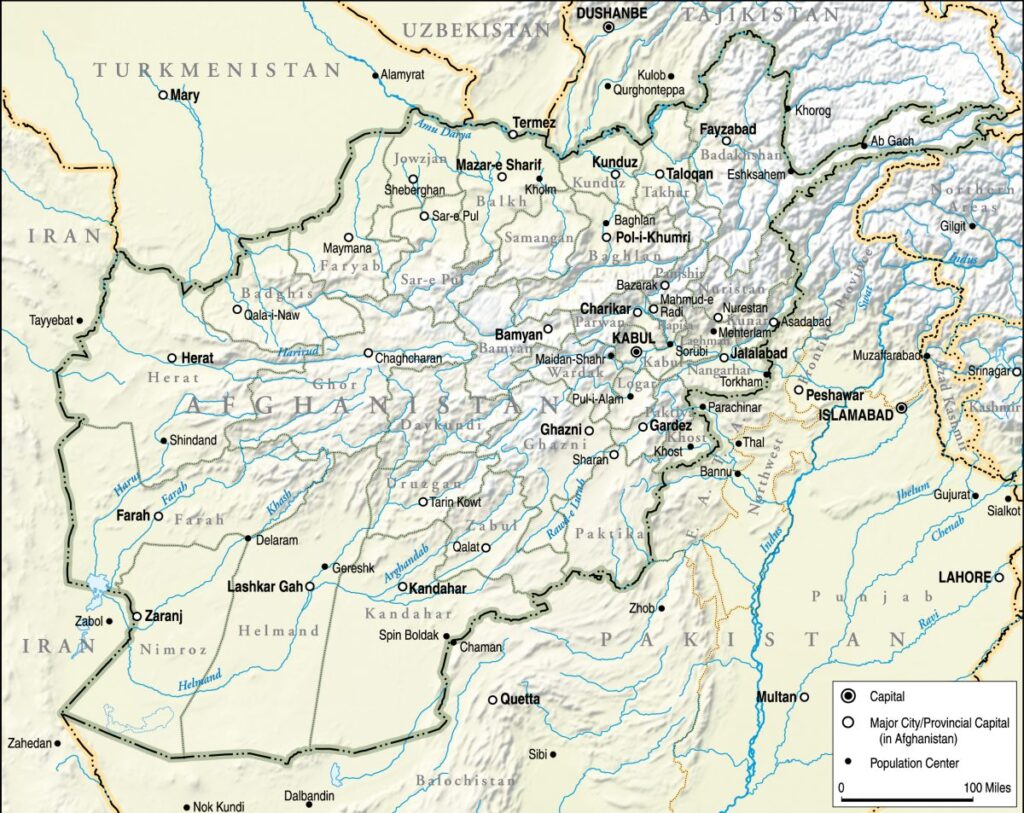

In order to properly understand the events of this past summer, it is necessary to first illustrate the situation in Afghanistan as it existed just prior to President Biden’s decision to withdraw from the country. Since the end of the U.S. and NATO combat mission in 2015, the government of Afghanistan steadily lost control of territory in the country. For example, according to FDD’s Long War Journal (LWJ), in November 2017, the government controlled 217 of Afghanistan’s 407 districts.12 By April 2021, it controlled only 129—a decrease of about 40 percent.13

At a macro level, in early 2021, the author used LWJ’s district assessments in conjunction with reporting from local sources (e.g., Afghan journalists) to identify 15 of Afghanistan’s 34 provincial capitals as being effectively surrounded by Taliban-controlled areas.a Thus, even before President Biden’s announcement in mid-April, the Taliban had heavily infiltrated areas immediately adjacent to major cities all across Afghanistan. This posture included the Taliban having severed many secondary roads—and even portions of Highway 1 (the primary “ring road” around the country)—in what The New York Times described in mid-2020 as a “slow creeping siege” of Afghanistan’s cities.14 In these efforts, the Taliban were likely aided by the release of 5,000 of the group’s prisoners by the Afghan government (completed in early September 2020), which was heavily pressured to do so by the United States in order to meet one of the terms of the U.S.-Taliban agreement.15 And the group was substantially assisted by financial, material, or diplomatic support that it had received for years from a variety of external actors (e.g., Russia, Iran, Gulf states).16 The most significant source of such support came from Pakistan, which also provided sanctuary and strategic advice for the group’s leaders as well as support to the recruitment, training, deployment, and recuperation of its fighters.17

In the immediate wake of the signing of the U.S.-Taliban Agreement in February 2020,18 the ANDSF entered into an “active defense posture,” which limited their actions “to impairing a hostile attack while the enemy is in the process of forming for, assembling for, or executing an attack on Afghan government elements.”19 While President Ghani ordered his security forces to go back on the offensive in a televised address in May 2020,20 the Afghan National Army (ANA) Chief of General Staff issued an order in June 2020 codifying the active defense strategy21 and the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) noted several months later that the ANDSF had maintained a defensive stance.22 The effects of the active defense posture could be seen in a decreased number of total operations involving Afghan Special Security Forces (ASSF; primarily the Commandos),23 increased operational tempo of the Afghan Air Force (AAF),b consolidation of hundreds of ANDSF checkpoints into a smaller number of patrol bases,24 and levels of Taliban-initiated attacks that were 45 percent higher than in 2019.c

Even with this slightly consolidated and defensive posture, the ANDSF were still arrayed across hundreds (if not thousands) of checkpoints and installations across the country, and the force consistently struggled with logistics and resupply of its positions.25 As a result, by 2020, the ANDSF had transitioned from a “pull” logistics system in which regional Army corps were responsible for requesting necessary supplies from Kabul and then providing them to the point of need for their assigned forces, to one in which the Afghan Ministry of Defense (MOD) utilized “strategic national convoys” to push logistics packages on routine timelines to regional units. By the end of 2020, however, even these convoys had become unreliable due to the Taliban’s disruption of the country’s road networks, so the ANDSF were increasingly reliant on the AAF conducting weekly logistics flights to regional locations.26

The ANDSF were also heavily reliant on contractors to maintain their equipment. With the exception of its Mi-17 helicopter fleet, the AAF was almost completely dependent on contract maintenance.27 In January 2021, the U.S. military entity advising the AAF stated that none of its aircraft were likely to be sustained as combat effective beyond a few months after the withdrawal of contracted maintainers.28 During 2020, the percentage of Afghan army vehicle repairs being conducted by Afghans (as opposed to contractors) was 19 percent, far below the goal of 70-80 percent.29 For the police, this number was seven percent, against a goal of 25-45 percent.30 d

For its part, by early 2021, the United States had reduced its footprint in Afghanistan to roughly 2,500 troops and 11 bases.31 These troops were focused primarily on partnered counterterrorism missions with ASSF and advising the ANDSF in four primary areas: strategy and institutional oversight/support (at the security ministries), aviation (the AAF), special operations (ASSF), and supporting functions (e.g., command and control, logistics) for the ANA.32 The United States provided significant support to these functions through the use of a Combined Situation Awareness Room and a set of Regional Targeting Teams. The most notable effect of these entities was to quickly bring airstrikes in support of ANDSF ground units, often within minutes of them being attacked by Taliban forces.33

Taken together, these observations paint a picture of slow, but steady degradations in security in recent years, a Taliban insurgency that maintained the initiative, had ample external support, and was well-postured to challenge the government across the entirety of the country, and an ANDSF that had mostly stopped conducting offensive operations and was heavily reliant on air support and U.S. advisors for both strikes and resupply, as well as contractors for maintenance of their equipment. In part due to these factors, a net assessment of the ANDSF and Taliban fighting forces that the author conducted in January 2021 for this publication concluded that after the withdrawal of U.S. advisors and air support from Afghanistan, the Taliban would likely have “a slight military advantage” over the ANDSF “which would then likely grow in a compounding fashion.”34 e These factors also led Kate Clark of the Afghanistan Analysts Network (AAN) to presciently observe:

As US troops withdraw over the next few months, the [ANDSF] can expect decreasing air support from its powerful ally and finally little or nothing at all. The Taliban’s current position of harassing [ANDSF], consolidating control of territory and focusing on extorting money from travelers and other citizens could morph into them massing forces and launching offensives on provincial centers. Would a withdrawing America deploy its air force in 2021 as it did to defend Kandahar and Lashkar Gah in the autumn of 2020 if the Taliban start attacking Afghanistan’s cities in the next few months? … The Afghan air force has been conducting aerial strikes, but if its deterrent power proves to be less potent, major Taliban offensives will become more likely, with grave losses of life to both combatants and civilians.35

April 2021

In the 16 days following President Biden’s withdrawal announcement, a number of key events took place. The Taliban declared that they would not attend a diplomatic conference that the United States had been trying to organize in Istanbul to reinvigorate the Afghan peace process.36 President Ghani declared that the Afghan government was “not at risk of collapse” after the U.S. withdrawal and assessments to that effect were a “false narrative.”37 Ghani’s assertions were bolstered by those of his own generals, who stated that the ANDSF were “ready to safeguard the nation”38 and “crush the Taliban” after the U.S. withdrawal.39 These comments stood in stark contrast to one by the commander of U.S. Central Command, General Frank McKenzie, who told the U.S. Congress that he was “concerned about the ability of the Afghan military to hold on after we leave, the ability of the Afghan Air Force to fly, in particular, after we remove the support for those aircraft.”40 The latter concern was amplified by the Pentagon spokesman’s announcement on April 27 that the United States would not continue to provide air support for the ANDSF after its withdrawal.41

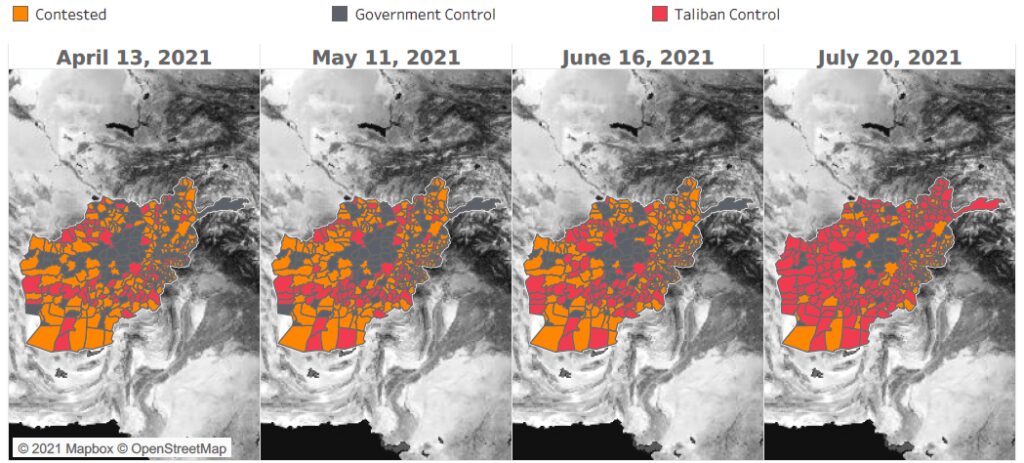

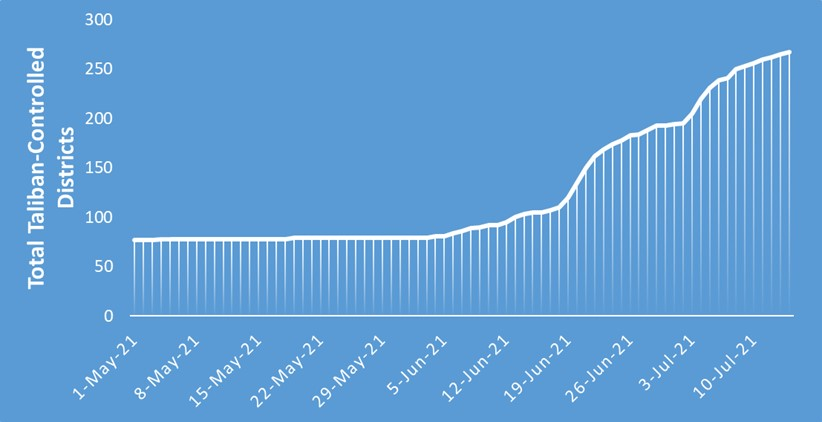

On the ground in Afghanistan, the Taliban initiated increased attacks across the country, with violence reported in multiple regions and in 24 of the country’s 34 provinces (e.g., Balkh, Kandahar, Herat, Nangarhar).42 The ANDSF began a deliberate clearing operation in Balkh province,43 and residents in lightly defended areas (e.g., Takhar) began to arm themselves in preparation for Taliban offensives.44 The Taliban began sending letters to Afghan politicians asking them for direct negotiations (in an attempt to bypass the government’s negotiating team in Doha and sow division among Kabul elites),45 and protests erupted in Faryab over President Ghani’s attempt to install a Pashtun loyalist as the governor of that province, further straining his relationship with the notorious northern strongman, Abdul Rashid Dostum.46 By mid-April, LWJ assessed the Taliban to be in control of 77 districts and the government in control of 129, with the remaining 194 districts contested (Figure 1).47

At the end of April, The New York Times published a scathing assessment of the readiness of the ANDSF to fight the Taliban alone. The report cited a number of factors that had been called out previously by independent analysts,48 such as slumping recruitment, high casualty rates, extreme corruption, and poor support of fielded forces, as major concerns that had resulted in one of the ANA corps fielding only about half of its authorized end-strength.49 The report cited a police lieutenant in Herat as saying, “I have been in this job for eight months, during this time we only got air support once. No one is providing support for us, our forces are hopeless and they are giving up on their jobs.”50 Of the lieutenant’s 30 police outposts, one had sold out to the Taliban, another had been overrun, and at least 30 of his officers had deserted.51 In neighboring Helmand province, the report described ANA bases completely surrounded by Taliban-controlled areas and wholly reliant on resupply by helicopter. According to the newspaper, “Soldiers in Helmand Province recently tried to negotiate with the Taliban, in hopes of abandoning their base without being attacked. The Taliban refused to let them go unharmed unless they left behind their equipment and weapons.”52

May 2021

On May 1, a date near the beginning of the traditional “fighting season” in Afghanistan,f the United States officially began withdrawing its forces from Afghanistan. The Taliban immediately surged attacks countrywide, with reports of intensified violence and additional district seizures by the Taliban in Uruzgan, Zabul, Helmand, Kandahar, Nangarhar, Kunar, Logar, Maidan Wardak, Baghlan, Ghazni, Balkh, Badakshan, Takhar, Kunduz, Herat, Faryab, and Farah provinces.53 Unlike in previous years, these attacks did not draw punishing airstrikes in return.54 In an ominous warning, Afghan parliamentarian Ahmad Eshchi said, “We are not well-prepared to save the cities.”55

The most rapid, immediate advances by the Taliban came during the first couple of weeks in May, in Baghlan province. In what would become a repeated scene across the country, a half-dozen army bases in Baghlan were overrun by the Taliban and at least 200 soldiers stationed at them surrendered. Commandos were then deployed to try to retake the lost areas, scores of families were displaced by the subsequent fighting, local “public uprising forces” began to arm themselves, and parliamentarians publicly bemoaned the government’s inability to secure the areas of the country that they represented.56

From May 13 to 16, separate unilateral ceasefires occurred on the parts of the government and the Taliban, to mark the Eid al-Fitr holiday. The U.S. commander in Afghanistan predicted that in the wake of the ceasefire, the Taliban would seek to “surge pressure on different provincial capitals.”57 This then happened, with Taliban attacks reported in 18 provinces (including in areas around their capitals) within two days of the ceasefires’ end.58

As the month progressed, the security situation in Baghlan deteriorated, alongside significant degradations in nearby Laghman province.59 Reports of ANDSF “tactical retreats” from bases and checkpoints increased in number and in consequence; reports surfaced of the ANDSF retreating not just from outlying posts, but from district centers as well.60 Through most of the month, protests in Faryab over Ghani’s governor appointment continued and intensified; these finally culminated on May 24, with Ghani’s acquiescence and recall of his candidate.61

On May 25, Afghan parliamentarians convened a session at which they grilled the country’s security leaders. While the latter attempted to shuffle blame onto Pakistan for its support to the Taliban and to downplay the significance of the threat—for example, by stating that the ANDSF were only fighting the Taliban in seven percent more districts than the year prior—Afghan lawmakers asked them such questions as: “What were the factors that led to the collapse of checkpoints in Laghman? Why did you not provide support to the soldiers while they were appealing for assistance?”62 A statement by the head of the National Directorate for Security (NDS) typified the security leaders’ responses: “Your security and defense forces are very determined and prepared, the enemy has suffered massive casualties and they do not have more strength.”63

By May 25, U.S. Central Command said the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan was between 16 and 25 percent complete.64 At the same time, ANDSF reinforcements sent to Laghman and attempts to consolidate positions there were unable to stem the Taliban’s gains; the group advanced to the central prisons in the provincial capitals of Laghman and Baghlan.65 Two days later, Australia shuttered its embassy in Kabul,66 and on May 29, the United States transferred one of its primary bases in the city (New Kabul Compound) to the ANDSF.67

As May came to a close, the head of the NDS claimed that the Taliban were having major leadership problems and had suffered significant setbacks across the country.68 He also claimed the ANDSF had killed 1,500 Taliban in a week.69 This was contrasted by escalating Taliban attacks on Lashkar Gah, the capital of Helmand province,70 and another scathing New York Times report on the negotiated tactical surrender of 26 outposts and bases—and four district centers—to the Taliban across four provinces. This report described what happened in Laghman in detail, along with similar scenes in other areas:

… as American troops began leaving the country in early May, Taliban fighters besieged seven rural Afghan military outposts across the wheat fields and onion patches of the province, in eastern Afghanistan. The insurgents enlisted village elders to visit the outposts bearing a message: Surrender or die. By mid-month, security forces had surrendered all seven outposts after extended negotiations … At least 120 soldiers and police were given safe passage to the government-held provincial center in return for handing over weapons and equipment.71

One of the elders involved in the negotiations said a key message that he delivered to local ANDSF forces was, “Look, your situation is bad — reinforcements aren’t coming.”72

June 2021

By the start of June, unofficial reports claimed that up to 100 Afghans (ANDSF plus civilians) were being killed or wounded by the Taliban per day,73 as a result of fierce fighting across at least 24 provinces.74 According to Fatima Kohistani, a parliamentarian from Ghor, the level of ANDSF casualties there reached the point of overwhelming the force’s ability to collect its dead. She stated, “Our martyrs are on the ground, but no institution takes action to even collect them.”75

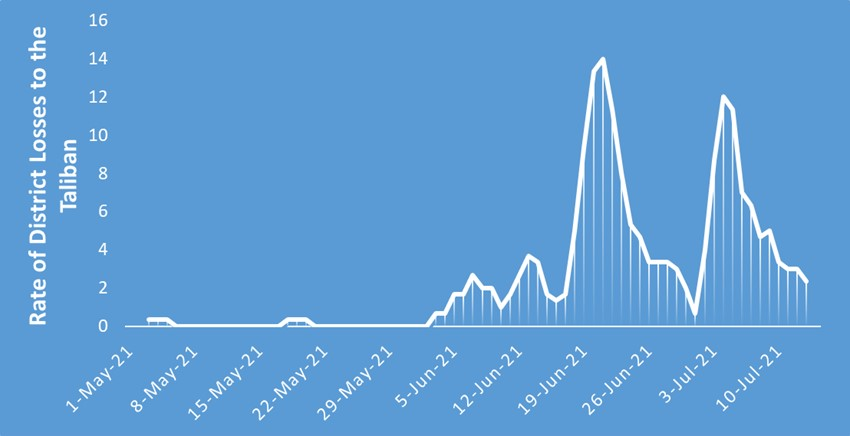

Reports of districts falling to the Taliban accelerated, with Taliban captures taking place in at least Baghlan, Laghman, Maidan Wardak, Faryab, Ghor, Uruzgan, Badghis, Takhar, Sar-e-Pul, Balkh, Farah, Herat, Helmand, Kandahar, Nuristan, Badakhshan, Ghazni, Logar, and Zabul provinces.76 By the middle of June, LWJ assessed that the Taliban controlled 104 districts outright, with another 201 contested, and the remaining 94 under government control—a gain of 27 districts for the Taliban and loss of 35 for the government since the announcement of the U.S. withdrawal in April (Figure 1).77

One standard talking point for the Afghan Ministry of Defense (MOD) at this time was that the ANDSF would “soon retake all those areas that have fallen to the Taliban.”78 But while the ANDSF did manage to retake several districts (e.g., Khan Abad in Kunduz), these gains came amid continued—and larger—losses in other regions.79 These losses led to increased criticism of the government by parliamentarians and military analysts. In particular, these audiences bemoaned the continued absence of the Minister of Defense (who was overseas for medical treatment), the appointment of yet another acting Minister of Interior, and the centralization of security policy in the Office of the National Security Council.80 Representative comments came from parliamentarian Nilofar Jalali Kofi, who stated: “I am sure that provinces will fall if the situation continues. The Defense Ministry is fully paralyzed. It is not responsive,”81 and from the parliamentarian Fatima Kohistani, who said that “the Ministry of Interior is on the verge of collapse.”82

Conspiracy theories also began to broadly surface around this time. As stated by parliamentarian Sayed Hayatullah Alimi, “The people think there might be a deal behind the scenes, they think that the government in a sense wants to arm the Taliban and give territory to the Taliban.”83 These theories were bolstered by a widely shared social media video of what appeared to be the Taliban accompanying a convoy of security forces retreating from an outpost and leaving all of their equipment behind,84 and by the active spread of corroborating misinformation by the Taliban.85

On June 17, a group of approximately 50 ASSF Commandos that had been sent to retake a district in Faryab were ambushed and overrun by Taliban fighters. The resulting death of 24 of the country’s most highly trained fighters became a national story—in part because the dead included Major Sohrab Azimi, a well-known special operator—and one that weighed heavily on the ANDSF’s morale.86 Other ANDSF units fought to their end as well. For example, in Faryab’s neighboring Shirin Tagab district, Afghan forces fought for days until they ran out of ammunition, at which point several hundred soldiers and police were captured or surrendered. The Taliban seized more than 100 vehicles and hundreds of weapons in the ensuing overrun of ANDSF positions.87

Over the next three days, the Taliban took a dozen additional districts across the country and briefly entered two provincial capitals in the north (Kunduz City and Maimana). Reports from the fallen districts indicated that, “In many cases, the security forces did not receive reinforcements and evacuated after hours of fighting … Many areas are falling to the armed opposition because security forces remain under siege and they have no equipment or supplies.”88 These trends continued through the end of the month, with the Taliban making additional net gains in districts across the country and pressuring additional provincial capitals (e.g., Taloqan, Pul-e-Khumri, Sar-e-Pul).89 As a result of these losses, Afghans increasingly began taking up arms to protect their own areas, under the banner of “public uprising forces.”90 g By June 21, President Ghani issued a call to arms for such forces to rise up across the country.91

On June 25, Presidents Ghani and Biden met at the White House. Among other points of discussion, Ghani asked Biden for additional air assets to help bolster the level of air support to ANDSF ground forces. Several days later, the Pentagon announced that it would provide 37 more Blackhawks and two more A-29 attack aircraft to the AAF, and that about 200 contractors would stay to support the AAF until September.92 The United States also reportedly used drones to conduct at least two airstrikes in support of Afghan forces battling to retake some areas in the north of the country.93

In the last five days of June, the Afghan Commandos pushed Taliban forces out of key areas of Pul-e-Khumri (Baghlan) and the ANDSF retook seven districts from the Taliban across Faryab, Baghlan, and Paktia provinces.94 The efforts were bolstered by public uprising forces.95 At the same time, the Taliban captured multiple border crossings, impacting neighboring Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan.96 Reports from the end of June consistently indicated multiple districts falling to the Taliban each day.97 By the end of the month, the AAN estimated that the Taliban had captured 127 district centers—with most of those having fallen in the latter half of the month.98 The resultant situation saw heavy fighting in and around numerous provincial capitals, most notably in Ghazni, Kunduz, Baghlan, Takhar, Faryab, Maidan Wardak, and Badakhshan.99

In total, during the month of the June, the ANDSF had only been able to recapture 10 of the 127 districts lost that month to the Taliban,100 and the two elements that were predominantly used for reinforcement and recapture operations—the Commandos and the AAF—were wearing thin. The commander of the Afghan Special Operations Command stated that the Commandos—who were already being overused prior to the U.S. withdrawal—had seen their activity increase by 30 percent since May.101 The AAF’s activity roughly tripled. In June alone, it conducted 491 airstrikes, or about 16 per day.102 The combination of increased demand for AAF support and a 75 percent decline in the number of contracted aircraft maintainers between April and June led to significant drops in aircraft readiness rates.103 For example, the readiness of the AAF’s UH-60 (Blackhawks) dropped from 77 percent in April/May to 39 percent in June.104 To deliver even the same number of flight hours, the smaller number of available airframes had to fly well beyond their recommended flight-hour limits. By the end of June, the main advisory element to the AAF estimated that all available airframes were exceeding scheduled maintenance intervals by at least 25 percent and aircrews were flying hours well beyond levels recommended by safety protocols.105

As the month drew to a close, the Taliban made several concerted pushes to capture Pul-e-Khumri (Baghlan) but were repelled by the ANDSF.106 The Italians transferred the last coalition base in Herat to the ANDSF and the Germans did the same in Mazar-e-Sharif.107 Tallies of casualties led to declarations of June having been the deadliest month in Afghanistan in decades. Tolo News estimated nearly 1,700 ANDSF and civilian casualties over 30 days, the majority of which were suffered in northern and central provinces.108 The MOD claimed (with little proof) to have killed or wounded nearly 10,000 Taliban fighters.109 Amidst this carnage, the chairman of Afghanistan’s High Council for National Reconciliation (Abdullah Abdullah) worried publicly that “the survival, security, and unity of Afghanistan is in danger.”110

July 2021

In early July, the MOD finally acknowledged that a “lack of equipment and delay in the delivery of emergency assistance” to its fielded forces were factors that had contributed to the loss of well over 100 districts to the Taliban in the month of June.111 The acting Minister of the Interior admitted that “war management issues” were the main reason behind the deteriorating security situation. He claimed that public uprising forces were making a positive contribution, though leaders of those forces countered that the government was not providing them with adequate support.112 The acting minister further stated that the ANDSF were “working on the plan to move to offensive status” and that “the centers of the cities will never collapse.”113 Vague pronouncements of “a new plan” being formulated had, by this time, become a common talking point for government officials. In a rare comment with more specificity, the commander of Afghanistan’s special operations forces stated, “Our main goal is to inflict as many casualties on the enemy as possible. Besides that, our goal is to protect major cities, highways and key border towns that are important for our major cities and the country.”114 His emphasis on attrition of Taliban forces aligned with daily statements from the MOD touting the number of Taliban killed or wounded by the ANDSF. For example, of the 410 tweets posted by the Defense Ministry’s Twitter account in July, 329 (80 percent) explicitly mentioned or showed Taliban casualties.115

On July 2, the United States withdrew from Bagram Air Force Base in the middle of the night and without informing the local base commander, a move that was interpreted as a lack of trust and confidence in the ANDSF.116 By July 6, U.S. Central Command announced that the U.S. withdrawal was more than 90 percent complete.117 Responding to the significant rate of Taliban advance, the Pentagon ordered the U.S. commander in Afghanistan (General Austin S. Miller) to remain in the country for an additional several weeks in an attempt to bolster ANDSF morale and “buffer the impact of the U.S. pullout on the Afghan people.”118 Reporting from regional sources in Afghanistan suggested that this had minimal effect. According to a civil society activist in Takhar, for example, there was “a large number of forces in the districts and in the provinces, but there is no morale and motivation.”119

Daily reports of Taliban captures of additional districts continued over the first half of the month.120 A number of northern provinces—especially Badakhshan and Takhar—were on the verge of collapse.121 The Taliban increasingly made gains in strategic areas as well, most notably around Kandahar,122 Herat (and its border crossing with Iran),123 and Kabul, where five of the capital province’s 14 districts were reported to be under significant threat.124 The Taliban did, however, continue to face stiff resistance in these strategic areas and other parts of the country, with regular reports of failed attempts against cities such as Ghazni.125

By the middle of the month, fighting continued in at least 20 provinces.126 While the ANDSF were able to retake a small number of districts, these successes were more than offset by additional losses elsewhere.127 Over the previous 30 days, Taliban forces had focused on consolidating their positions and using this posture to generate additional pressure on the country’s cities and central government. By mid-July, LWJ assessed that the Taliban controlled 216 districts—a gain of 112 since mid-June. The government controlled 73, a decrease of 21; 118 districts remained contested (Figure 1). The Taliban also continued to capture more border posts, including Spin Boldak, a major crossing point between Pakistan and Afghanistan.128 And the group controlled all but three of the district centers along the southern arc of Highway 1 from Zabul to Herat.129

With these gains, the Taliban were able to make advances against a number of provincial capitals, including in Takhar, Kandahar, Helmand, Ghazni, Faryab, Kunduz, and Laghman.130 In Herat, regional warlord Ismael Khan rallied his militiamen to defend the city alongside the ANDSF,131 while President Ghani visited Balkh province. There, he assured the nation that security would improve within three months and that “the Taliban’s backbone will be broken.”132 In the wake of his visit, the warlord Abdul Rashid Dostum publicly complained about the government’s failure to provide support to the public uprising forces in the north.133 Ghani went on to attend a summit in Uzbekistan, where he claimed that 10,000 jihadi fighters had entered Afghanistan from Pakistan in June.134 He then visited Herat City, as 17 of the province’s 19 districts—and its dry port with Iran (Islam Qala)—were in the midst of falling to the Taliban. According to local sources, many of these districts fell with little to no fighting, likely indicating the broader application of local negotiation tactics that the Taliban had earlier employed successfully in places like Baghlan and Laghman. Contrary to Ghani’s claims during his visit that the government had plans to retake the fallen districts, no new operations were launched to do so.135

From July 20 to 23, the Taliban and the government separately ceased operations to allow Afghans to observe the Eid al-Adha holiday.136 President Ghani used the holiday occasion to deliver a speech in which he claimed that the government was working on a new security plan that would improve the situation in three to six months.137 The commander of the 209th Army Corps in the country’s north claimed that his forces would “soon launch our offensive operations to recapture the areas that have been lost.”138

In a joint press conference on July 21, U.S. Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin stated that all U.S. forces would leave Afghanistan by August 31. General Milley asserted that a “negative outcome, a Taliban automatic military takeover, is not a forgone conclusion.”139 In support of this assertion, he offered that while the Taliban controlled about half of the country’s districts and was pressuring half of the country’s provincial capitals, none of the latter had yet fallen.140 In the few days ahead of this press conference, the United States reportedly conducted several more “over the horizon” airstrikes in support of ANDSF positions.141 General McKenzie said such strikes would continue, along with contracted logistics support, funding, intelligence sharing, and strategic advising.142 He stated that he and Afghan leaders “had very good dialogue on the government’s defense plan to stabilize the security situation” and that “the Taliban are attempting to create a sense of inevitability about their campaign but they’re wrong. There is no preordained conclusion to this fight. Taliban victory is not inevitable.”143 Nonetheless, the United States reversed its stance of not facilitating the departure from the country of Afghans waiting for Special Immigrant Visas and instead arranged for the first flight of 200 applicants to depart Kabul on July 30.144

As July drew to a close, the Taliban captured key districts near Kandahar City (Arghandab, Dand), attacked the city’s prison, and infiltrated into some of its neighborhoods.145 The group’s fighters pressed in on Herat, where Ismael Khan publicly bemoaned the failure of the government to send reinforcements.146 The same situation existed in Lashkar Gah, where the Taliban had launched a sizable attack from all four directions after capturing nearby Marjah and Garmsir districts,147 and for which The New York Times described a situation in which residents had lost hope in the government being able to defend the city.148 Taliban fighters also infiltrated some parts of Kunduz City, where the ANDSF were unsuccessfully trying to root them back out.149 Reports of ANDSF units surrendering to, or retreating from, the Taliban continued nationwide,150 alongside reports of vicious fighting151 and civilian casualties that were the highest ever recorded in Afghanistan.152 As The New York Times described: “The government’s response to the insurgents’ recent victories has been piecemeal. Afghan forces have retaken some districts, but both the Afghan air force and its commando forces—which have been deployed to hold what territory remains as regular army and police units retreat, surrender or refuse to fight—are exhausted.”153

August 2021

On August 1, President Ghani held an event to tout a new “e-governance” initiative. At the event, he stated that one of the key problems on the battlefield had been delays in getting payments to soldiers and policemen. He beseeched government officials to avoid corrupt activities and to not make him “ashamed” in front of the country’s partners.154 He also emphasized his new plan to turn the security situation in the country around in six months, stating that a big part of the plan was the nationwide mobilization of public uprising forces155 and the expansion of the Commandos from 20,000 to 45,000 special operators.156 In the wake of his speech, Afghans questioned his strategy as the Taliban captured their first provincial capital (Zaranj, in Nimruz) after ANDSF forces there fled to Iran on August 6,157 and then their second (Sherberghan, in Jowzjan) on August 7 after public uprising forces led by Dostum’s son failed to stem the Taliban’s advance.158

As these two capitals fell, fierce fighting continued to take place in Herat and Lashkar Gah. Government reinforcements finally arrived in the two cities, but not before Taliban fighters had advanced to the central parts of each one.159 In Herat, public uprising forces fought alongside the ANDSF, the people showed solidarity with their protectors by chanting “Allahu Akbar” from their rooftops at night, and the combination of forces and esprit pushed the Taliban back.160 In Lashkar Gah, the Army ordered citizens to evacuate the city so as to limit the number of civilian casualties and reduce the Taliban’s ability to use them and their homes as shields.161 Fierce fighting also took place in the north: reports indicated heavy clashes between the ANDSF and local forces, and the Taliban, in the capitals of Kunduz, Takhar, and Badakhshan, among others.162

By August 8, after over a month of fighting, the capitals of Sar-e-Pul, Kunduz, and Takhar fell.163 Ramazan, a resident of Takhar, told reporters that “The security forces and public uprising forces have been fighting for the past 40 days and standing against the Taliban without the support of the central government. Unfortunately, the lack of equipment and central government’s support has caused Taloqan to fall to the Taliban.”164 A deputy police chief in Kunduz City, where fighting had been ongoing for weeks, said, “We are so tired, and the security forces are so tired … we hadn’t received reinforcements and aircraft did not target the Taliban on time.”165 Reporting from The New York Times corroborated this sentiment:

The Taliban’s siege of Kunduz … began in late June, and they wore down government soldiers and police units in clashes that raged around the clock … a Kunduz resident said he had heard a barrage of gunfire as security forces and Taliban fighters clashed in the alley just outside his home. As the fighting intensified, about 50 members of the Afghan security forces massed in the alley. But the government soldiers appeared worn down. “They said that they were hungry — they had run out of bread.”166

The next day, the Commandos launched an attempt to retake Kunduz City,167 while Aybak, the capital of Samangan, fell to the Taliban without a shot. This was due in part to the defection of a former parliamentarian and prominent militia located there, likely as a result of informal deals made by local officials with the Taliban.168

While the Taliban were hyping these victories on social and traditional media, the government made no public acknowledgment of the losses. Instead, the MOD continued to highlight Taliban casualties169 and government officials promoted #SanctionPakistan—a hashtag first promoted by former Canadian diplomat Chris Alexander on Twitter in early June.170 While five provincial capitals were falling, #SanctionPakistan became the top trending hashtag in Afghanistan on multiple social media platforms.171

By August 9, the Taliban’s victories in Kunduz and Takhar allowed them to consolidate and mass forces in Baghlan and Badakhshan provinces, whose capitals then fell. As The New York Times described, in these cities, as elsewhere:

… witnesses and defenders described twinned crises of low morale and exhaustion in the face of unrelenting pressure by the insurgents. Mohammad Kamin Baghlani, a pro-government militia commander in Baghlan Province, described a sudden fall in Pul-i-Khumri after withstanding a Taliban siege that had stretched on for months. “We were under a lot of pressure, and we were not able to resist anymore,” he said. “All areas of the city fell.” Bismullah Attash, a member of [the] provincial council in Baghlan Province, confirmed that account, saying that despite months of heavy fighting around Pul-i-Khumri, the final fall on Tuesday was mostly bloodless.172

In response to these captures—as well as the fall of Farah province173—President Ghani held an emergency meeting of senior officials on August 10 to discuss the formation of a centralized command center for public uprising forces, to better support and coordinate their efforts to combat the Taliban alongside the ANDSF, as was occurring in Herat.174 This idea was proposed by several political figures, including Dostum, who had recently returned to the country to lead efforts to defend Mazar-e-Sharif175 with some initial success.176 On the same day, Afghanistan’s acting minister of finance fled the country.177

On August 11, the 217th ANA Corps collapsed and was overrun at the airport outside Kunduz City.178 President Ghani traveled to Mazar-e-Sharif, where he reportedly assigned Dostum as the lead for all military efforts in the country’s north,179 where fierce fighting continued in Jawzjan and Balkh provinces.180 Meanwhile, the Taliban renewed its push for cities in the south and west. Attacks sharply increased against Kandahar, where the Taliban managed to capture the prison and free nearly 2,000 inmates.181 In Lashkar Gah, the Taliban captured the provincial police headquarters after a 20-day siege.182 In Uruzgan, the ANDSF repelled a concerted effort by the Taliban to take the capital, Tirin Kot.183 The Taliban advanced on Herat from all four sides and surged forces against the capital of Badghis as well—both efforts were repulsed by a combination of ANDSF and public uprising forces.184

The next day, the governor of Ghazni province negotiated his surrender, and that of Ghazni City, to the Taliban in exchange for safe passage to government-controlled territory. Upon arrival at the latter, he was arrested by government forces.185 On August 13—after fierce battles that had lasted nearly a month, preceded by siege periods spanning much longer—Herat, Kandahar, and Lashkar Gah fell to the Taliban, cementing the group’s control of the entire Pashtun south.186 A day later, the capitals of Logar and Ghor provinces also fell, reports emerged of local elders in Uruzgan and Zabul negotiating the surrender of those provinces,187 and the United States announced the deployment of 3,000 troops to facilitate the evacuation of its embassy from Kabul.188

Between August 14 and 15, the government lost any and all control of its forces. In some areas, the ANDSF continued to fight;189 in others, they withdrew of their own accord from the cities to bases nearby;190 and in others still, they were asked to leave by local leaders who wanted to spare their cities the destruction that had been levied on Lashkar Gah in previous weeks.191 On August 14, President Ghani addressed the nation, saying that his top priority was the remobilization of the ANDSF and that he had “started widespread consultations within and outside the government” to that end.192 A day later, six of the seven ANA Corps had surrendered or dissolved,193 and in the wake of the Taliban saying they would not enter Kabul by force,194 President Ghani fled the country195 and the United States declined the Taliban’s request to take responsibility for the security of all of Kabul and instead focused on securing the city’s airport so as to facilitate the safe passage of its personnel from the country.196

Key Themes from the Collapse

There are many themes that emerge from close consideration of the events between President Biden’s announcement of the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan and the Taliban’s capture of Kabul. Here, the author will focus on six that are directly related to the collapse of the ANDSF.

The ANDSF did not collapse in 11 days: Contrary to General Milley’s statement to this effect,197 the ANDSF did not wholly collapse in a matter of days. As early May 2021 reports from Baghlan and Laghman provinces made clear, some ANDSF units were overrun—while others began to withdraw or surrender their positions to the Taliban—immediately after the United States began its withdrawal and the Taliban launched their offensive. These scenes were repeated across the country in the months that followed. The result was a domino effect (Figure 2), with each successive district’s loss contributing to increasing Taliban momentum and perceptions of an eventual Taliban victory.

Even before the U.S. withdrawal began, however, the ANDSF were in a precarious position, as noted by analysts,h the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR),198 and media outlets at the time.199 Since the end of the U.S./NATO combat mission and shift to advising in 2015, the ANDSF had consistently lost ground to the Taliban and steadily become more reliant on U.S. air and logistical support. In other words, the ANDSF’s collapse—while it occurred over the course of nearly four months and was surprising to serious observers even on that timeline200—had been years in coming.

The United States did not give the ANDSF everything they needed to be independently successful: Contrary to President Biden’s assertions to this effect,201 the United States did not give the ANDSF everything the force needed to be independently successful against the Taliban. Biden unintentionally intimated as much himself, when he acknowledged that the United States “provided for the maintenance of their air force … [and] provided close air support.”202 There were, in fact, at least three key aspects of an effective fighting force that the ANDSF did not have after the U.S. withdrawal began.

The first was the ability to logistically sustain itself. As described above, there were numerous instances throughout April and May 2021 in which ANDSF forces tried to stand and fight against the Taliban. After a period ranging from a few days to some number of weeks, however, these units inevitably ran out of supplies and were rendered combat ineffective. The general inability of the ANDSF to conduct organic resupply was a trait long recognized and never fully addressed by the U.S. military in Afghanistan. As recently as December 2020, DoD listed “improving logistics” as its number-four priority effort for ANDSF development, behind “leader development,” “reducing the number of vulnerable checkpoints,” and “countering corruption” (all of which also contributed to issues with logistics).203 As just one example of the ANDSF’s inability to logistically sustain their forces, DoD assessed that “the ANDSF have struggled at the national level to maintain visibility of [their] on-hand logistics, which has had an impact on ANDSF operations.”204

The second aspect that the ANDSF lacked, especially as the Taliban’s campaign wore on, was the ability to provide timely reinforcements and air support to forces in the field. As the United States completed 90 percent of its withdrawal between May 1 and early July 2021, it removed all of its air support assets and the vast majority of its advisors, and it collapsed its footprint in the country to a small presence at the U.S. embassy and the airport in Kabul. With this rapid withdrawal went the vast majority of the contractors that were maintaining AAF aircraft and the ANDSF’s vehicle fleet. The net result was two-fold: dramatic increases in the operational tempo of the AAF and Afghan Commandos, and significant decreases in the readiness of these forces over the month of June. As the weeks of independent ANDSF operations wore on, the AAF and Commandos wore out and the Ministry of Defense found itself unable to provide timely reinforcements and air support (e.g., airstrikes and logistics airdrops) to forces in the field. As described above, once soldiers and police on the frontlines knew that reinforcements and airstrikes were unlikely to come, they were less likely to stand against the Taliban and less likely to be successful even if they did.

The third element that the ANDSF did not have was sufficient leaders to command and guide the force. As the author described in a recent Politico article,205 the United States has recognized leadership development as a key problem for the ANDSF since at least 2008. And yet, in its December 2020 assessment, DoD still listed “leader development” as the top challenge facing the force.206 Despite consistent efforts by individual U.S. military officers to mentor and train ANDSF leaders during their time in Afghanistan, the United States on the whole failed to produce enough leaders for the ANDSF to be independently successful. This was largely because the United States failed to recognize that the shortfalls in ANDSF leadership were a symptom of an underlying root cause: the lack of sufficient and effective institutions that could educate, train, and manage Afghan military leaders at scale. As DoD’s budgeting documents show, efforts to develop such leadership development institutions were consistently under-resourced relative to tangible items like helicopters and vehicles.207

The ANDSF did fight: Contrary to popular perceptions, in many cases and places, the ANDSF fought valiantly to defend the country. It is true that in the immediate aftermath of the United States beginning its withdrawal, some ANDSF units deserted or surrendered without a fight. But all across the country in the months that followed, ANDSF members fought and died in battles against the Taliban. At times, ANDSF losses were so great that they exceeded the force’s ability to evacuate its dead and wounded from the battlefield.208 To further illustrate the level of violence, over the first 10 days of August 2021, over 4,000 wounded Afghans were treated by the Red Cross alone.209

These battles featured individual stories of heroism, such as that of Ahmad Shah. He and 14 other policemen were attacked at their checkpoint near Kandahar City; despite being wounded, he fought the Taliban for 18 hours before being rescued by reinforcements.210 And they featured tales of units—most notably, the Afghan Commandos—who fought repeatedly and to the point of exhaustion.211 As one researcher described, “Although Afghanistan’s security forces seemed demotivated, unsupported and weak, there were those that would have, and did, continue to fight, but there was little or no central coordination, no chance of help or backup or resupplies, and a scarcity of clear messages, or leadership, from the Palace.”212 Under these conditions, the ANDSF units that did make a stand were eventually and inevitably left with little choice but to flee, surrender, negotiate withdrawal, or fight to the death. That even a fraction of them chose to do the latter belies claims that the ANDSF simply did not fight.

The ANDSF were poorly served by Afghan political leaders: As the U.S. withdrawal began, President Ghani was in the midst of a political crisis of his own making via the appointment of a Pashtun loyalist as the governor of Faryab. This, combined with continuous squabbling with other political leaders such as Abdullah Abdullah over negotiations with the Taliban in Doha, created unnecessary distractions at a pivotal time for the country’s security forces. Even worse, Ghani and his small inner circle, led by National Security Advisor Hamdullah Mohib, failed to act on the recommendations of U.S. and Afghan security leaders in late 2020 to consolidate ANDSF forces into a smaller array of more defensible positions, focused on strategic elements such as key roads, cities, and border crossings. According to both the U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken213 and independent media,214 Ghani refused this advice, fearing it would make his government look weak. In that meeting, Mohib reportedly stated, “We’re not giving up one inch of our country.”215 As some observers noted, “While the Taliban were planning for the U.S. withdrawal, the government failed to take on board what a post-U.S. war would look like or apparently prepare for it. Indeed, the Afghan elites behaved as if they did not believe the U.S. would ever actually leave.”216

All throughout the Taliban’s offensive as the United States withdrew, there were again calls from Afghan parliamentarians, military analysts, and U.S. and Afghan military officials to pull the ANDSF back to a set of more defensible and strategic positions. By late July 2021, after a call with President Biden in which he impressed upon Ghani that “close air support works only if there is a military strategy on the ground to support,”217 Ghani finally gave the orders to enact such a plan. However, at that point it was too late to matter: the Taliban had already taken control of at least 144 additional districts since their offensive began on May 1.218 As one analyst described:

The government did not give the impression of having created a war room, nor did it exude any sense of urgency. President Ghani and his small inner circle of confidantes seemed to approach the situation either as a piece of policy that people needed to get behind or a psychological war that could be won, or at least weathered, by buttressing morale and framing the narrative … There seemed to be little connection to, or interest in, the actual situation on the ground.219

The ANDSF were poorly served by their own commanders: Throughout the United States’ attempts to build the ANDSF, there were consistent reports of rampant corruption among ANDSF leaders,220 which included stealing pay from soldiers and police, selling fuel and ammunition on the black market, and buying shoddy equipment and low-quality food at cut rate prices and pocketing the difference.221 Notably, these activities lasted until the very end of the ANDSF’s existence.222 The poor treatment of soldiers and police by their own leaders well before the U.S. withdrawal started meant that the ANDSF began the post-U.S. era from a place of generally low morale.

In addition, while ANDSF leaders were prohibited from pursuing a consolidation and defense strategy by the country’s political leadership, they compounded the problem in two ways. The first was through the continuous deployment of ASSF Commandos to areas that had been recently taken by the Taliban. Once the dominoes of districts—and then cities—began to fall, rather than attempting to anticipate the Taliban’s next moves and pre-empt them, ANDSF leaders instead chased after the problem of the day, with little in the way of lasting results and to the eventual exhaustion of those forces being sent willy-nilly across the country. The second was via a fixation on Taliban deaths as both a metric of success and a primary means of government propaganda. Senior leader statements, MOD spokesman comments and press releases, and the MOD’s social media presence all placed strong emphasis on Taliban body counts—and often unbelievably inflated ones.223 This repeatedly signaled to Afghans and external observers that the MOD lacked a coherent plan (beyond killing for its own sake) and called into question the veracity of other information that the MOD was releasing to the public.

The Taliban strategy overwhelmed and demoralized the ANDSF: The Taliban designed and executed a brilliant campaign that identified, and then systematically exploited, the ANDSF’s weaknesses, of which three were particularly significant. The first was the ANDSF’s posture. When President Biden made his withdrawal announcement, the Taliban were well-positioned to launch a nationwide offensive, having encroached on the majority of district centers and nearly half of the provincial capitals across the country. The ANDSF were poorly postured to defend across such a wide space,224 especially as the traditional fighting season in Afghanistan was just getting underway.225

The second weakness that the Taliban exploited was the ANDSF’s critical capability shortfalls: logistics, maintenance, air support, quick response forces, and command and control. As the U.S. withdrawal began, the Taliban initiated what could be described as a “flowing water” strategy. This consisted of two key facets. First, attack everywhere, all at once. Second, hold and lay siege where resistance is met; advance where it is not. As two prominent scholars described, this is a time-tested strategy:

It aims at forcing the enemy to exhaust themselves trying to defend the cities while their trade and communication lines falter, using the countryside as a staging ground and its population as a recruiting pool. While it is not known whether the Taleban have studied Mao’s, Ché Guevara’s or Regis Debray’s handbooks of guerrilla warfare, their strategy seems to [have been] taken from these textbooks.226

This approach resulted in slow but steady gains for the Taliban during April and May 2021, but by mid-June, the ANDSF were overwhelmed trying to defend, resupply, and re-attack everywhere and the avalanche of district collapses began (Figure 2). The Taliban, on the other hand, seemed to have effectively addressed their own logistics and resupply requirements. While information on how they did this is lacking, a journalist in Kunduz City at one point remarked that local Taliban fighters had at least two months of supplies on hand227—vastly more than most ANDSF units appeared to have.

The third weakness targeted by the Taliban was the ANDSF’s morale and cohesion. The ANDSF started from a low bar of morale due to the predatory nature of their leadership and, as the author has previously described in this publication, the ANDSF were a force with generally low levels of cohesion due to a variety of structural factors.228 A major component of the Taliban’s campaign was, therefore, deliberate and devastating psychological operations (PSYOP) designed to target these weaknesses. These operations took two forms. The first was relatively quiet outreach to local ANDSF units to convince them to defect, surrender, or withdraw. These efforts were conducted by Taliban “Invitation and Guidance Committees.”229 Once the Taliban had severed the roads used to resupply an ANDSF position, members of these committees would conduct deliberate, consistent outreach to ANDSF leaders at that position. The Taliban’s offer was to spare their lives—and sometimes, those of their families—if the troops would abandon their outposts, weapons, and ammunition. The Taliban often upheld their end of this deal by giving those who had surrendered amnesty, money, and free passage back home, but not before they filmed the exchange for propaganda purposes.230 As districts began to fall, the Taliban also apparently tried to convince some ANDSF members that the United States had already made a deal that would allow the group to take over the country.231

The second form of PSYOP employed by the Taliban was overt media operations. As described by one researcher, the Taliban uploaded “a deluge of carefully curated images and videos on social media”i alongside their capture of ANDSF positions and district centers.232 More specifically:

Videos with fighters running through towns … were followed by footage of Taliban fighters wandering through government buildings or sitting behind desks and on sofas. These were followed by videos of mass prisoner releases … showing crowds of men carrying bags walking along the road. Also widely distributed were photos of the Taliban flag raised in various locations, interviews with or statements by the new local leadership, and countless images of vehicles and weapon arsenals … Much of the footage [sought] to convey a message of law and order and seem[ed] intended to reassure and intimidate in equal measure.233

These elements of PSYOP supported an overall narrative that the Taliban sought to advance, which was one of inevitability.234 U.S. military leaders seemed to sense the dangerousness of this narrative taking hold, as evidenced by comments from Generals Milley and McKenzie in mid-July that no outcome in Afghanistan was pre-ordained.235 But the Afghan government did nothing to effectively counteract this narrative, choosing instead to focus its messaging on the number of Taliban it was killing and attempting to deflect blame for the collapsing situation onto Pakistan.

Lessons from the Collapse

There are many lessons that the United States should learn from its experience in Afghanistan, and there is little doubt that much will be written along those lines in the years to come. Here, the author will offer three major lessons that flow from the themes just discussed.

The ANDSF’s failure had many fathers: The ANDSF were not set up for success when the United States began its withdrawal. The weakness of the ANDSF’s posture and its low morale are attributable to Afghan political and security leaders, as is the government’s abysmal failure to devise and implement an effective counter-strategy as the Taliban campaign unfolded. But the ANDSF’s shortfalls in leadership and their structural weaknesses in critical support areas such as logistics and maintenance, as well as the force’s heavy reliance on air power, were issues that the United States knew about years in advance of its withdrawal.j Prior to President Biden’s decision to leave, the United States had failed to adequately address these weaknesses—and in the case of air power, it had consistently made decisions that exacerbated them. For example, in 2017, DoD assessed that “the AAF has proven more than capable of maintaining the Mi-17 [helicopter]. The AAF are largely self-sufficient with the Mi-17.”236 And yet, due primarily to political preferences to move away from Russian-made equipment, the United States decided to provide the AAF with UH-60 (Blackhawk) helicopters, which required retraining hundreds of pilots and crew chiefs237 and for which the United States anticipated an indefinite reliance on contract maintenance.238 The U.S. government also failed to prioritize mitigation of these weaknesses as its withdrawal commenced, and it largely ignored the “contagion dynamic”239 of ANDSF desertions that unfolded as its withdrawal rapidly progressed.

The U.S. model of security assistance requires reform: Between Vietnam, Iraq, and Afghanistan, there are now three examples of large-scale U.S. security assistance efforts—designed to build or rebuild a foreign military wholesale—that have resulted in dismal failures.240 As described in detail in several SIGAR lessons learned reports, these failures stem in part from the lack of dedicated elements of the U.S. government to oversee and conduct these types of major security assistance efforts.241 But even more critical is that the U.S. model for security assistance focuses heavily on developing tactical capabilities, providing material goods, and encouraging mirror-imaging of U.S. forces. Far less emphasis is placed on critical non-material factors such as leadership, logistics, maintenance, and institutional oversight, and properly accounting for partner-specific attributes such as available human and financial capital.242 As the case of Afghanistan illustrates so clearly, this approach—especially when applied at scale—fails to create a foreign military that is capable of conducting effective operations and independently sustaining those operations over time. Instead, it creates a foreign military that is addicted to U.S. support for its effectiveness, if not also for its long-term sustainment. The collapse of the foreign military when that support is withdrawn—especially if it is withdrawn quickly—should be seen not as a bug in the U.S. model of security assistance, but rather as a feature of it.k

Greater emphasis on non-material factors is needed in future security force assessments: There is widespread agreement that, even among those who were watching and studying Afghanistan closely, the collapse of the ANDSF over the course of four months was surprising. While U.S. intelligence estimates on the ANDSF remain classified, public discussions of them indicated that facets of the intelligence community believed the ANDSF could prevent the government’s collapse for at least six months, if not significantly longer.243 The author’s own assessment—based on a comparison of the situations in Afghanistan at the beginning of the Soviet and U.S. withdrawals—was that the ANDSF would be able to slug it out with the Taliban around the country’s cities until 2022, at which time the force would either fail or a new stalemate would be established.244 How did this author, and so many others, get the assessments wrong? The answer lies in not putting enough weight on the non-material weaknesses of the ANDSF, and not anticipating how aggressively and effectively the Taliban would campaign against those weaknesses and how dramatically they would be affected by the speed of the United States’ withdrawal. For example, in this author’s January 2021 net assessment of the ANDSF and Taliban fighting forces, he compared five aspects of each force and concluded that after the U.S. withdrew, the Taliban would have a slight military advantage that would compound over time based on those factors.245 Four of the five factors were material in nature (size, material resources, external support, force employment) and only one was non-material (cohesion). Had the author included the other two major non-material factors that featured prominently in the Taliban’s campaign—morale and PSYOP—they would have tipped the scale to a strong, if not overwhelming, Taliban military advantage. These factors are much harder to assess than material ones; nonetheless, the case of Afghanistan makes clear how vitally important their inclusion is for the accuracy of any security force assessment.

Conclusion

As one analyst recently commented, “it is important to note that [Afghanistan] did not go from relative stability to utter chaos overnight.”246 As the author has described above, all of the trends that unfolded in rapid fashion in the four months after President Biden’s withdrawal announcement were present before his speech. In other words, the seeds of Afghanistan’s collapse—and those of the ANDSF’s collapse as well—were sown by U.S. and Afghan officials’ decisions long before the United States began its withdrawal. Recognition of this, however, does not support the narrative being advanced by U.S. officials that the ANDSF collapsed in 11 days, that these forces had everything they needed to be independently successful, and that they simply did not fight. Given the ANDSF’s inability to consistently resupply forces engaged in combat with the Taliban, to sustainably provide them timely air support and reinforcements, and to effectively lead line soldiers and police in battle on their own—critical weaknesses that the United States acknowledged as recently as December 2020247—the fact that they hung on for four months after the United States began its withdrawal in earnest belies claims that the ANDSF abandoned a winnable fight in less than a fortnight. Even worse than being incorrect, this narrative obscures the true causes of the ANDSF’s collapse and stands as an official obstacle to learning from what happened.

Looking ahead, it will be crucial for the United States to correct its narratives about the ANDSF’s collapse, to conduct truly introspective assessments of its attempts to build an independent security force in Afghanistan, and to make corrections to the way it develops and assesses foreign security forces going forward. If three data points constitute a pattern, the United States’ failure to develop security forces at scale in Vietnam, Iraq, and Afghanistan suggest that failure to take these steps now will very likely result in the future collapse of some other security force currently being built by the United States overseas.