India’s Deployment Of US Weapons To Fortify Disputed Border With China In Tawang Plateau: Does It Portend Larger Geopolitical Conflict? – OpEd

What began as a friendly relationship between India and China on April 1, 1950, when India became the first non-socialist bloc country to establish diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic of China, has now evolved into the region’s most dangerous adversary. The United States’ Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) encouraged Tibet’s uprising against China, eventually seizing control of the fledgling resistance movement. The worst relationship between India and China begins in 1959, when the CIA assists in securing the Dalai Lama’s safe passage to India, and the subsequent launch of one of the Cold War’s most remote covert campaigns with the establishment of the Tibetan exile administration in 1960.

Three years later, in 1962, the Sino-Indian border dispute erupted into a major conflict between India and China. Despite diplomatic relations, an all-out political war broke out between India and China in 1967, prompting Beijing to openly declare its support for the Naga national movement. It prompted the London Observer to publish a story titled “China has become involved in the 14-year-old conflict between the Nagas and the Indian Government.” It also piqued the United States’ renewed interest in the Naga issue, which encompasses a much larger geographical area – including Assam, Arunachal Pradesh, Manipur, and Myanmar – than the Nagaland state boundary in India; additionally, the “Kashmir strategy” compelled Pakistan and Bangladesh to renew their support for the Naga national movement, despite reports of undivided Pakistan providing aid from 1962 to 1965.

On June 15, 2020, the deadliest clash between India and China in 45 years occurred in Galwan Valley, with the death of twenty Indian soldiers and four Chinese soldiers. According to experts on both sides. Brahma Chellaney, for example, has called it the “tipping point” in India-China relations, while Hu Shisheng has called it the “lowest point since the border war between them in 1962.” Former India’s national security adviser Shivshankar Menon describes what happened in Ladakh as a “fundamental and consequential shift in behaviour, a successful salami-slicing manoeuvre” by China, whereas Hu stated unequivocally that the “conflict was not incidental,” but rather a “inevitable” consequence of the Modi government’s “high risk, high yield” policy.

Meanwhile, amid the ongoing high tensions surrounding the Galwan Valley situation, a relatively quiet event occurred concerning the Indo-Naga political talks, in which an informal dialogue between the Government of India (GoI) and the National Socialist Council of Nagalim (NSCN) was resumed in Delhi on August 12, 2020, following a nine-month stalemate. It should be noted that The “historic” Indo-Naga Framework was signed in 2015, and just as the ongoing talks were about to break down at the end of October 2019, Indian media outlets reported on November 22, 2019, that prominent NSCN leaders are already camping in China to seek Chinese assistance. The clashes in the Galwan Valley compelled India and China to make unprecedented political and individual statements and actions. On September 7, 2020, India retaliated further by holding a public funeral and wrapping the body of the company leader of the Special Frontier Force (SFF), a special unit tasked with conducting covert operations behind Chinese lines, in both the Indian and Tibetan flags. In the aftermath of the deadly border clashes, India increased import duties on Chinese goods. However, on February 19, 2021, China released on-site video of a Galwan clash in June 2020, adding another wrinkle to India-China relations. India responded quickly, identifying the young captain as a Naga from India’s 16th Bihar Regiment, who was leading the charge against the Chinese soldiers. The presence of a Naga in the standoff elicited an equally strong reaction from some of China’s most influential media outlets. In the midst of the standoff in the sensitive Tawang sector, a frenetic negotiation between the Nagas and India had begun in New Delhi in the second week of October 2021.

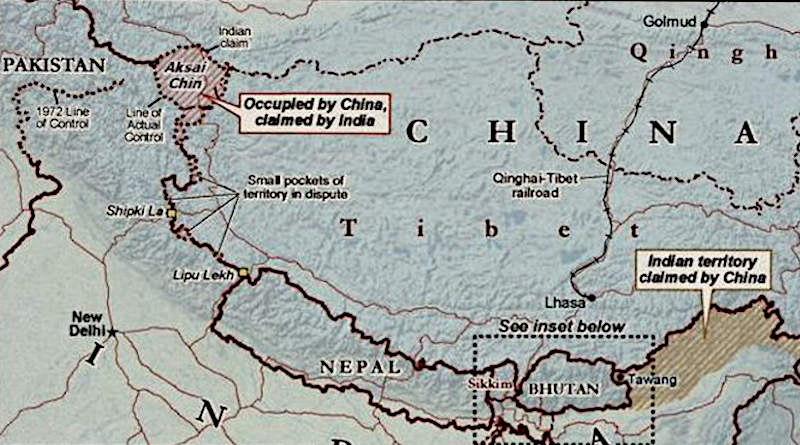

Despite the first high-level meeting of Indian and Chinese foreign ministers to address ongoing border aggressions on July 14, 2021, tensions remain high, with military buildups on both sides, particularly in areas where capability gaps exist, such as air power, ground-based air defenses, and missile forces. Prior to the 2017 Doklam or Donglang crisis, both countries’ military buildups were limited; however, in the aftermath of the crisis, neither India nor China ceased their activities in the border region. China, for example, has significantly expanded and upgraded its military infrastructure along the Indian border in 2019, whereas India’s attempts to modernize its military have met with repeated setbacks, and it has struggled to deal with the 2020 Ladakh crisis. With the Ladakh crisis, India has begun to formulate a broader strategic military infrastructure drive, with the India’s Ministry of Defense announcing on September 14, 2020 that it will construct six new runways and 22 military helicopter facilities across Ladakh. On September 24, 2021, it was also reported that India is about to overhaul its largest military reorganization to counter China, following a long-delayed plan.

Under Modi’s government, India’s Act East Policy (AEP) is gradually evolving into Act Indo-Pacific policy to counter China in line with the US Indo-Pacific strategy. The European Union’s (EU) Indo-Pacific strategy also marks the beginning of the EU’s new approach to the region, with the US dimension viewed as critical. With India’s deployment of newly acquired US-made weaponry demonstrating its new offensive capabilities, such as howitzers, locally manufactured supersonic cruise missiles, and Israeli-made unmanned aerial vehicles in the disputed territory of Arunachal Pradesh or 藏南地区, China also passed the new border law, prompting India to express concern that the new law would exacerbate the already-rising border tensions between India and China. Thus, the Asia-Pacific region, or the newly constructed Indo-Pacific strategy, will further define the Asia-Pacific region, with a focus on territorial disputes. The India-China conflict is a classic example of how the most disparate cultures have met through power gambits since the Cold War era, and it has the potential to worsen as a new “hot” power front for larger geopolitical conflict.