The Banking Crisis In Afghanistan – Analysis

The Biden administration’s decision to bar DAB’s access to forex reserves has caused tremendous hardships to the Afghan people. Creating new sustainable forms of revenue must be the current focus.

Introduction

This August, the Interim Taliban Administration (ITA) completed a year in Afghanistan after taking over last year. The withdrawal of foreign troops, enabled by the signing of the Doha Peace Agreement between the United States (US) and the Taliban ultimately resulted in the fall of Kabul. Since the disintegration of the government of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, the insurgent group has been flailing to govern the country, if at all its actions can fall under the ambit of ‘governance’.

An abrupt disruption of aid and assistance post the Taliban’s takeover, followed by the isolation of the country’s financial institutions, and a consequent banking crisis has led to a vacuum in the economy with people struggling to make ends meet and businesses closing their shutters. Understanding this ‘economic phase of the war’, as termed by the ex-governor of the Afghan Central Bank, necessitates an enquiry into the banking crisis in the country which exacerbated the humanitarian catastrophe that the international community is trying hard to mitigate.

How is the Afghan economy structured?

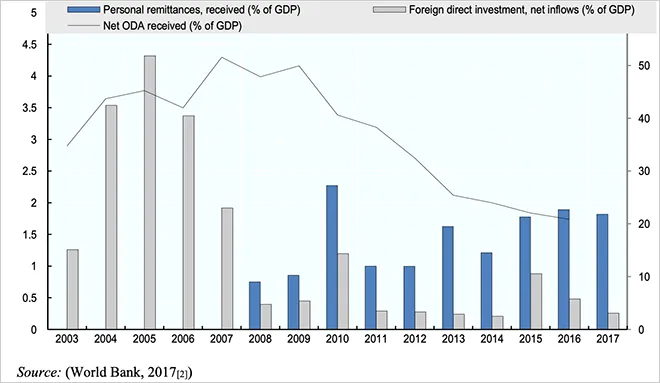

Between 2001–2021, the country sustained itself on aid from the international community led by the United States and its allies, Foreign Direct Investments (FDI), as well as remittances from Afghans abroad. With the creation of the Afghanistan Reconstruction Trust Fund (ARTF) in 2002, 34 donors came together to inject US$10 million into the reconstruction of the country. These efforts, whilst successful in making enormous strides in healthcare, education, and other indicators, failed to permeate the deeply entrenched ‘networks of access’ that run in the country, consequently being inadequate in stimulating domestic competitiveness or advancement of tradeable sectors. In a ministerial conference in Geneva in November 2020, the international community committed to giving US$13 billion in aid to Afghanistan from 2020-2024 for basic services and sustaining the peace process. This aid amount was to be complimented by ‘domestic resource mobilisation, efforts to reduce corruption, improving governance and introducing structural reforms.’ However, once the Republic was replaced by the Emirate of Afghanistan, all these commitments were set aside.

Historically, the discourse on Afghanistan’s economic system has oscillated between ‘centralisation and fragmentation of power’. Because of a heightened sense of regional autonomy and a weak centre, the state has never had effective control over the entire country. A general acceptance of the principle of Wasita, i.e. the influence of connections in enabling success, has also been prevalent, rendering efforts to develop a stable and equitable economy focused on building capacity and promoting productive sectors, unworkable.

Whilst almost 80 percent of the economy is in the informal setup, there are over 700,000 private businesses in the country, contributing to over half of the country’s GDP in 2018. The sector has always been mired by uncertainty because of the civil war, the inability to access finance, land, and the endemic corruption which defined public life. The drawdown in the number of troops since 2011–12 and the consequent reduction in aid and investment led to an economic burnout. The private sector investment also fell by 24 percent between 2011 and 2015. Failure to diversify the economy and the non-availability of well-paid jobs in the field led to the concentration of growth in a few centres, with poverty still pervasive.

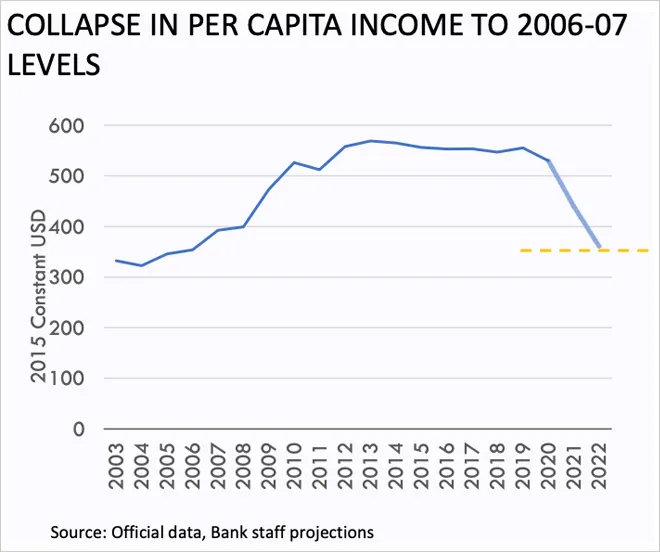

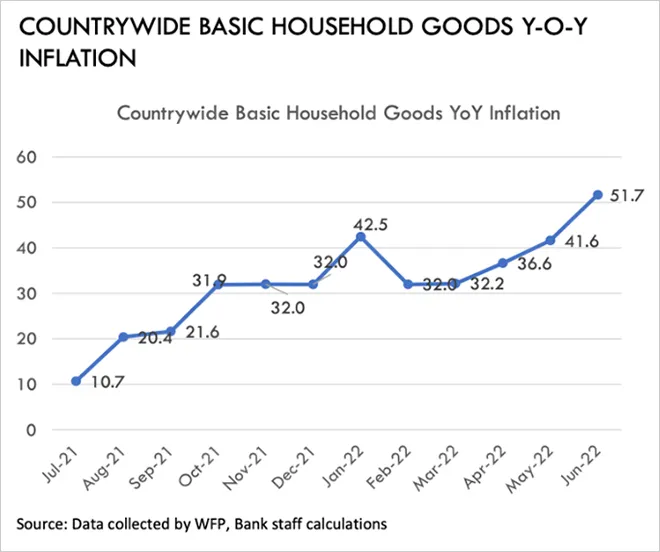

With the advent of the Taliban, these issues multiplied with uncertainty regarding the new administration still being a cause of concern for businesses, followed by the crisis in the banking sector, and a slump in demand. According to the World Bank, the ITA collected AFN 100 billion in revenue in the year, but concerns about transparency and the allocation process still abound. Inflation also skyrocketed with the year-on-year inflation on household goods seeing a 30 percent jump since August 2021. Over the year, whilst there was a slight uptick in the demand for labour, it was mostly seasonal with varying rates of unemployment in each province. Businesses scaled back their operations by laying off employees, cutting down salaries and relying more on cash (57 percent) and hawala transactions (31 percent) with the percentage of firms depositing money in banks dropping to just 12 percent, as opposed to 82 percent before August 2021. Only a few sectors like agribusiness, wholesale, and retail trade showed more resilience. The construction and services sector faced the biggest pushback as a corollary to its high reliance on donor and governmental support. Whilst businesses tried to engage in a dialogue with the Taliban to address some of these concerns, an inability to comprehend and resolve the issues escalated the situation.

The status of Afghanistan’s forex reserves

Post coming to power, the Taliban placed its functionaries —most of whom were under US sanctions—in the top echelons of the government. In response to this, the US along with its allies stopped the inflow of aid to the country, preventing the disbursal of US$2 billion provided by the World Bank to pay salaries through the ARTF. Other international organisations also followed suit. The decision to isolate the Afghan central bank, the Da Afghanistan Bank (DAB) from the international banking system, the financial community and other countries’ domestic banks was one of the most consequential actions of the Biden administration. This policy practically barred the DAB’s access to approximately US$9 billion of foreign exchange reserves which it had deposited in international banks with the majority amount in the US Federal Reserve bank of New York. This decision is more prominent now than ever, with the Taliban and US officials engaged in an on/off dialogue to decide the future of those reserves and their utility in easing the hardship of the people.

The debate over the disbursal of these funds raises several questions. The decision to engage with the insurgent group to find a solution would indicate granting of de facto legitimacy to a terrorist organisation. However, choosing not to, can in turn exacerbate the hardships of the Afghan people. The situation becomes more complicated as it also involves questions on the applicability of US domestic laws. The reserves are caught in litigation by the victims of the 9/11 terrorist attacks seeking damages from the Taliban. In an executive order passed on February 11 2022, the Biden administration blocked half of the total reserves for the benefit of the Afghan people and the remaining half became a part of the litigation making them unavailable unless the case was settled. The litigation shows every sign of extending well into the future, as it involves the question of sovereignty and applicability of the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act in the US, under which the assets of a sovereign central bank are exempt from punitive actions. The decision becomes more complicated as Washington doesn’t recognise the Taliban as the sovereign authority of the country.

To find a solution to the humanitarian crisis, the US has been in touch with the Taliban officials to sketch out a mutually acceptable framework for disbursal of the US$3.5 billion of the US$7 billion held for the ‘Afghan people’. The agenda of the talks was to chart out ways to release the funds for fulfilling the humanitarian needs of the people, and use them as a means of ‘recapitalising’ the bank and enabling it to fulfil its functions which would inject much-needed liquidity in the country. In talks in July on the sidelines of the Tashkent conference, both sides exchanged proposals. The US, wanting to ensure that the funds are allocated in the service of the Afghan people, demanded the appointment of a third-party controller who would be responsible for the disbursal. However, the Taliban, worried about the emergence of a ‘parallel’ central bank, refused to remove its appointees from the top posts but agreed, at least ‘in principle’ to allow third-party contractors to audit how the bank is disbursing the amount. The recent killing of Al-Zawahiri in a posh locality in Kabul put a spanner in the works of the negotiations finding a way to make the DAB functional again.

The way forward

The crisis in Afghanistan is multi-dimensional. Apart from the economic turmoil inside the country, the lingering effects of COVID, the high energy prices because of the crisis in Ukraine, the spate of natural disasters that hit the country, along with the floods in Pakistan which affected disbursal of aid through the land route have made any linear solution to the situation impracticable. One year later, questions about the extent of engagement with a terrorist group and prioritising humanitarian considerations are still being debated. Whilst there is a general acceptance of the need to manage the disaster that is unfolding in Kabul, there is hardly any conversation on how the private sector, which is a significant force in the country can ameliorate the situation. The focus of the international community should be on enabling the private sector, along with aid organisations, to engage with the financial institutions in a limited manner, with steps taken to ‘ringfence’ the central bank from the insurgent group to ensure that the money is being used where it is meant for. Whilst ensuring this will be a herculean task—as the talks between the Taliban and the US make evident—a conversation on ensuring DAB’s autonomy does need prioritisation. However, even if the funds are released fully, they will, at best, provide limited succour unless the focus shifts on creating new sustainable forms of revenue in the country.