Chinese Incursions In The South Pacific – Analysis

In 2006, deadly riots in the capital of Tonga, Nuku’alofa devastated the government and business districts in the small-island nation. The cause of the riots that lasted almost a month was the delay by the government in initiating democratic reforms.

As tensions between the pro-royalists and pro-democracy factions rose, King Tupou VI, attributed this delay to differing opinions which were “not irreconcilable and can be resolved through dialogue”. Post-riots, the Tongan government commenced citywide reconstruction, alongside the renovation of the Royal Palace and construction of a new wharf – all financed by the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Chinese swiftness in servicing loans, a penchant for supporting authoritarian regimes, and the lack of sustainability factor in infrastructural loans were pivotal in Tonga’s choice of a lender.

China’s initial loan of US$ 65 million has today swelled to approximately US$ 133 million. Tonga, already devastated by the tsunami and volcanic eruption in 2021, now owes US $195 million or 35.9 percent of its GDP to China, of which two-thirds alone is owed to the Exim Bank of China. Tonga is struggling to repay as challenges arising from climate change, the impact of the disruption of global supply chains, economic shocks due to the pandemic, and heavy public spending, have impaired the government’s financial health.

Tonga’s woes symbolise a larger debt sustainability problem in the South Pacific, rousing fears that the region will fall into financial distress, becoming more vulnerable to China’s diplomatic pressures. China has already emerged as the region’s largest lender by disbursing bilateral loans amounting to US $1.3 billion between 2012 to 2022. Chinese loans account for More than 60 percent of Tonga’s external debt, as well as nearly 50 percent of Vanuatu’s overseas debt is owed to China. On the other hand, representing almost a fourth of its overseas debt, the Chinese debt to Papua New Guinea amounts to nearly US $590 million.

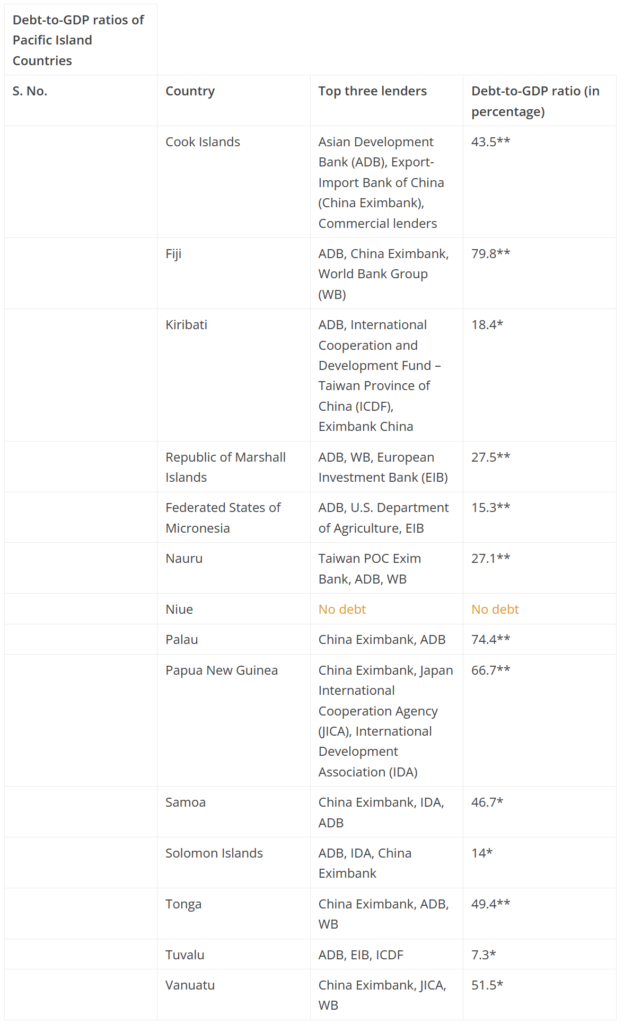

An analysis of the debt-to-GDP ratio for the Pacific Island Countries (PICs), reveals the prevalence of significant debt sustainability risks apropos of Chinese bilateral lending in the region. The Joint World Bank-IMF Debt Sustainability Framework for Low-Income Countries benchmarks debt sustainability at 50 percent in a debt-to-GDP ratio. Six out of the nine pacific island nations that currently borrow from China—Vanuatu, Samoa, Tonga, Fiji, Cook Islands, and Palau—are effectively at a 50-percent warning threshold. Except for Fiji, these nations are likely to go beyond the aforementioned threshold under the currently prevalent circumstances. Tonga and Vanuatu are in alarming economic distress due to their borrowing patterns. Vanuatu’s debt to China stands out, given that in late 2018, the government took a Chinese loan for a cross-country road project worth US $4.1 billion. This project markedly increases the debt sustainability risks for Vanuatu because of the additional financial burden that this loan puts on the already heavily indebted nation.

The sheer scale of China’s lending, the lack of monitoring and evaluation mechanisms, and inefficiency in servicing credit to borrowing nations with dubious debt sustainability ratings, – coupled with inadequate credit terms for loans to the PICspresents a looming threat to future debt sustainability in the South Pacific. Thus many critics have called China’s lending spree in the region a ‘debt trap’. Beijing needs to restructure its debt sustainability approaches entirely, to prove them otherwise.

Opacity in loans terms

China’s lending spree in the Pacific has been criticised for the opacity of its terms and conditions. The Cook Islands, for instance, has disapproved of some of the Chinese projects on its soil. These include a China-financed courthouse, police station, and sports stadium, which are now facing structural problems due to substandard construction. The concessional loans followed the typical Chinese modus operandi of awarding contracts to Chinese construction companies and even importing labour and material from China. In other words, China is servicing loans to the Pacific Island nations and generating overseas employment in the region for its nationals.

Chinese bilateral loan agreements comprise comprehensive confidentiality clauses, emphasising non-disclosure of terms, loan figures, collaterals, and sometimes even the very existence of loans. The fact that China’s credit flows aren’t reported to international organisations and that it has a comprehensive aid database is why 50 percent of Chinese credit flows to recipient nations are hidden.

Chinese contracts in regional locations receiving significant Chinese flows, especially in the South Pacific, are also riddled with rampant corruption. . Opaque procurements and contracting mechanisms in the Memorandums of Understanding (MoUs) between both parties permit China to use official credit doled out as loans and employ Chinese labour and material in the recipient nations. Such manoeuvres insulate Chinese firms from local, national, and foreign firms competition firms which may have otherwise bagged projects. Beyond facilitating corruption and decreasing the competitiveness of native firms and people, opaque lending patterns make an informal base of borrowers in the South Pacific accessible to China, as has been claimed in Africa regarding the financial agreements between African media companies and China’s state banks.

China’s endgame and Taiwanese support in the South Pacific region

What is China’s endgame in the region? China’s rise in the South Pacific region is linked with its greater endeavour to emerge as a great power, as its economy and global reach increase. An overseas lending spree has facilitated state-owned Chinese businesses’ participation in foreign infrastructure projects. Thus, Chinese firms have undertaken infrastructural projects throughout the region, ranging from the Luganville Wharf, Vanuatu, to the countrywide water system in the Cook Islands. Notably, the contract, resources, and labour employed, were all Chinese – built by Shanghai Construction Group and China Civil Engineering Construction Company, respectively.

A problematic recurrence in all China-financed ports and wharves in the South Pacific is that they are big enough to handle warships. Their design raises suspicions given China’s keenness to undertake military and policing partnerships in the Pacific, as evident by the leaked bilateral security deal with the Solomon Islands and the security pact spanning the entire South Pacific, as proposed by Foreign Minister Wang Yi in May 2022. The far-reaching deal envisions a close partnership between China and the Pacific Island Countries and spans critical security services and sectors such as maritime mapping, capacity building for law enforcement personnel, cybersecurity, and critical minerals partnerships.

That China is aware of its overseas loans being a powerful strategic tool is evident by the Asian giant’s recent possession of the strategically important Hambantota Port in Sri Lanka. The South Pacific is also critical for China because of the question of Taiwan’s diplomatic recognition. The PICs house almost a third of the countries with whom Taiwan has formal diplomatic ties. China considers Taiwan as a ‘renegade province’ and hopes to use serviced loans to employ diplomatic and economic pressures on governments to tip the scales to their side in the regional Taipei-Beijing rivalry.

Geographic isolation, the size of these islands, and the enormous strategic benefits to China for relatively nominal investments make China a dangerous player in the region. China’s regional incentives are based on the geostrategic significance of the shipping lanes and these islands’ vast untapped maritime and land-based resources. Isolating Taipei over the last decade is a bonus that Beijing has wrested from its inroads in the South Pacific.