Afghanistan’s international isolation cracks Taliban leadership: “Infighting is probable”

Leading members of the fundamentalist group blame supreme leader Hibatullah Akhundzada for the country’s unsustainable drift

The clash of internal currents is wearing the movement down a year and a half after it regained power in Afghanistan.

He did not even appear in public when the Taliban regained power two decades later. Hibatullah Akhundzada praised his movement’s advance in every corner of the country and celebrated the historic seizure of Kabul in August 2021 as one more. The Taliban’s armed uprising against the decaying Afghan army put the fundamentalist group back in command and automatically made him supreme leader. “Thank God, we are now an independent country. [Foreigners] should not give us their orders, it is our system, and we make our own decisions,” he declared at the time. But he did not leave his lair in Kandahar for months. He waited until July to visit for the first time the capital of the country he rules with an iron fist, not to address the Afghan people, who barely recognise him, but to attend a closed-door assembly attended by 3,000 other clerics. He once again dodged the cameras.

The death of Mullah Akhtar Mohamed Mansur in a US drone strike on Pakistani soil led to his ascension to the top of the movement in 2016. The Shura, or Supreme Council, the Taliban’s governing body, then anointed him as his successor because of his religious and organisational credentials, demonstrated in his early days as a member of the Vice and Virtue Police and years later as a deputy leader of the group, of which he was one of its earliest members. There was little else to explain his surprising appointment beyond being considered a great ideologue. Akhundzada, unlike his predecessors, did not make his mark on the battlefield. He has no recognised military experience. Even so, he swept all other contenders. It was at this time that his first and only image to date was published in the press, disseminated by the fundamentalists to feed the myth. No further visual records exist.

Hardly anyone knows the supreme leader in depth. Akhundzada has always lived in hiding, secluded in Kandahar, his hometown, subject to a much stricter regime than his fellow members, something that can be explained by his position of authority and relevance within the movement. It is also because he has sought to recapture the essence of the group — discretion and severe discipline. Information about his life has been known in dribs and drabs, and information about his death has been much more common. Although the incessant rumours of his demise have been denied time and again by his subordinates.

The reality is that Akhundzada rules Afghanistan without leaving Kandahar, the country’s second largest city. A poorly maintained road of just over 490 kilometres separates Kandahar from Kabul. The drive takes about 10 hours. But he is omnipresent from a distance. The supreme leader oversees all Taliban commissions, charged with executing his decisions. He has the final say in matters related to religion, politics, the security apparatus, health, education and culture. He has the final say in everything. He handpicks ministers, provincial police chiefs, regional clerical councils and so on. Nothing is beyond his control. Today’s Afghanistan is drawn in his image.

No one influences the supreme leader’s decisions more than the clerics and tribal leaders around him in Kandahar. “His style of governance is a heterodox theocracy, mixing Islamist concepts drawn from the Sunni Deobandi madrassas of Pakistan and Afghanistan, and combining them with rural Afghan village traditions,” Graeme Smith, a senior consultant with the International Crisis Group, a Brussels-based research organisation, told this reporter. “They are against social and educational reforms. They also reject bringing other ethnicities into the political environment,” adds Pakistani analyst Fraz Naqvi in an interview with Atalayar.

It is not the lack of reform that has exacerbated the crisis, but the adoption of a series of measures that violate the fundamental rights of half the population. An edict issued by the supreme leader at the end of the year banned women from working in NGOs, prompting a dozen organisations to leave the country in solidarity with their Afghan counterparts. The Taliban also prevent them from working in the health sector. Earlier, Akhundzada had already prohibited girls over the age of 12 from attending school despite the reluctance of some members of the group. As a result, more than 3.5 million young Afghan girls were forced to drop out of school.

The measures have worsened the situation in a country already hit by an unprecedented humanitarian crisis. The UN deputy special representative and humanitarian coordinator for Afghanistan, Ramiz Alakbarov, said in January that GDP had fallen by as much as 35% since the return of the Taliban. The cost of the basic food basket had risen by 30% and the unemployment rate by 40%. These figures, coupled with the isolation into which the fundamentalists are dragging the country, an isolation that is jeopardising even aid and investment from abroad, have set off alarm bells in Kabul. The crisis is beginning to crack the coexistence of the different currents that make up the fundamentalist movement.

The Haqqani network revolts

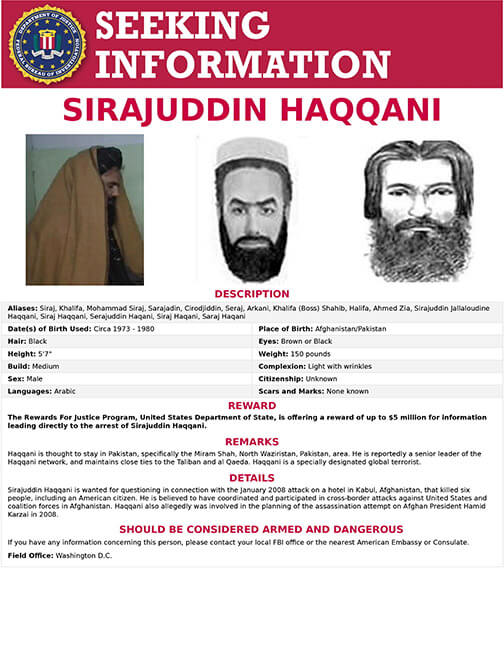

“Monopolising power and damaging the reputation of the whole system is not in our interest,” warned Taliban heavyweight Sirajuddin Haqqani. The current Interior Minister delivered a speech on 11 February at the graduation ceremony of an Islamic school in Jost province, calling on his people to “be patient, behave well and interact with the people to heal their wounds”. Haqqani called on them to act in a conciliatory manner to prevent people from rejecting both the Taliban and the religion.

“Today we consider ourselves so entitled that attacking, challenging and defaming the whole system has become commonplace,” added Haqqani, who is also the deputy emir of the fundamentalist group. “This situation cannot be tolerated any longer…. Today I have a different responsibility, and that is to get closer to the people.” At no point did he mention the supreme leader. But Haqqani’s remarks, which were recorded on video and shared at breakneck speed on social media, were interpreted as a direct criticism of Mullah Akhundzada, launched from Jost province, a familiar stronghold because of his membership of the Pashtun Zadran tribe, which rivals the rest of the Zadran clans.

An excerpt from the speech of HE Khalifa Sirajuddin Haqqani in Khost:

Our responsibilities are to heal the wounds of our people & bring ease to them. It’s not our aim to be like a dictator & rule the people in such a way that they suffer at our hands. pic.twitter.com/RrKzjwAs3x

— Muhammad Jalal (@MJalal0093) February 12, 2023But Haqqani, who has recently spoken out in favour of higher education for women, and who holds regular talks with Western diplomats, is Afghanistan’s most wanted. The FBI has a $10 million bounty on his head. He is the heir to the Haqqani network, a terrorist group that has been implicated in the murder of hundreds of civilians and security forces in suicide bombings, mostly US soldiers. In 2008, the Treasury Department designated the current Afghan government interior minister as a “global terrorist”.

The Haqqani network is also an internal current of the Taliban movement, founded by his late father Jalaluddin Haqqani in the 1970s, which came to prominence during the anti-Soviet jihad in Afghanistan a decade later. “It is considered a branch of the Afghan Taliban but operates independently and has a more diffuse command structure,” reports The Counter Extremism Project. “After the Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan, Jalaluddin Haqqani formed an alliance with the Taliban and supported the growth of al-Qaeda. Even before Osama bin Laden moved his base of operations to Afghanistan, Haqqani took the extraordinary step of issuing communiqués and appeals for alliance with al-Qaeda affiliates across Africa.”

But the Interior Minister was not the only member of the Taliban government to show his displeasure with the supreme leader. Defence Minister and one of the group’s heavyweights, Mohammad Yaqoob Mujahid, spoke out four days after Haqqani to call on the government not to be “arrogant” and to respond “to the legitimate demands of the nation”. The criticism is particularly significant. Mujahid is the son of the Taliban’s founder, the historic Mullah Omar. He is also the movement’s second deputy emir.

The third dissenting voice to join this critical camp has been the deputy prime minister, Abdul Salam Hanafi, who said in early February that the Taliban could not claim to run an independent nation without ensuring a sound education system. “The duty of a mufti [a Muslim jurist whose decisions are considered law] is not just to say forbidden, forbidden, forbidden. When you prohibit something, you must also indicate the solution for it,” he warned precisely from Kabul University, a site that is off-limits to women.

“These comments may indicate an attempt to react against recent draconian social measures, mostly restrictions on women’s basic rights and freedoms, which Akhundzada and his circle of advisors appear to have advocated,” Smith writes. Analyst Vanda Felbab-Brown writes in the pages of Brookings that “the Taliban regime has progressively hardened and become more authoritarian and dogmatically nineties in the past year”. But she blames the Directorate General of Intelligence (DGI), attached to Sirajuddin Siraj Haqqani’s Interior Ministry, and the Ministry of Promotion of Virtue and Prevention of Vice, for having become “the main tools of repression”.

The rest of the group is silent. No one has come out in public to defend the supreme leader. No one except Taliban spokesman Zabiullah Mujahid. Appointed deputy Information and Broadcasting Minister after the group’s return to power, Mujahid has been gaining power internally as he has become the visible face of the group to the international media. The spokesman denied that there were rifts between the different families that make up the group, accusing “some foreign circles” of “misusing” the statements of its leaders to sell an internal division. But he then left a message: “If anyone criticises the emir, the minister or any other official, it is better, and Islamic ethics also say so, that he should express his criticism directly and in secret”.

Hours after taking Kabul, the Taliban, especially through Mujahid’s regular press appearances and tweets, promised the international community that they would change the way they govern, banishing the usual practices of their first period in power in the 1990s. There would be no torture, no public executions, no ethnic persecution and no restrictions on women’s rights. The Taliban spokesman pledged to integrate other ethnic groups into government decisions while maintaining a smooth relationship with their neighbours. But Akhundzada, with near absolute power, has not fulfilled any of these aims. Instead, the supreme leader has swayed the more pragmatic Taliban factions.

“Over the past 17 months, we have seen time and again that the Taliban government’s primary objective remains purely and narrowly religious, that is, they see themselves first and foremost as charged with establishing and expanding a puritanical theocratic Islamic state in which the sharia is maintained, as they understand it, by fear and force,” Timor Sharan, associate professor at Oxford University’s Global Security Programme and author of Inside Afghanistan: Political Networks, Informal Order, and State Disruption (Routledge Contemporary South Asia Series, 2022).

On paper, it is obligatory to follow the supreme leader’s orders. But one of the group’s negotiators with the Trump administration in Doha, Sher Mohammad Abbas Stanikzai, stressed during another graduation ceremony, this time in the eastern province of Logar, that “it is not obligatory to agree with the orders of the leaders if they do not conform to Islam”, according to statements reported by EFE.

“Obedience to the emir” is a basic tenet of the Taliban movement, so visible disagreements with its leadership are unusual. Such discussions took place behind closed doors in the 1990s. The fact that such disagreements have peppered public forums might suggest a slightly different political culture under the second Taliban regime,” Smith notes. But the International Crisis Group consultant is cautious: “I would not want to overstate the degree of openness: the Taliban remain, by and large, a secretive movement”.

Factional fighting

Smith concedes, however, that we are witnessing a debate among the Taliban over the future direction of the regime and the country. “So far, these disagreements do not represent serious fissures within the Taliban movement. In Afghan politics, an argument is no big deal if no one is shooting guns at each other, and so far, the Taliban’s military cohesion seems solid,” he qualifies. Fraz Naqvi, for his part, explains that “disagreements are very common in such groups. However, they have not come to light until now. Before, the founding members of the Taliban movement were alive, so disagreements remained veiled. This is not the case today. Moreover, the geopolitics have also changed.

The Pakistani analyst believes that infighting is quite possible. “Some of the members are not in favour of protecting other non-state groups, especially when there is regional pressure; however, the hardliners believe that these groups could act as a deterrent to the international community,” he tells Atalayar.

“The current power lies with the hard-line faction, which controls most of Afghanistan’s security networks and the entire apparatus. This hardliner is overseen by the Haqqanis. Since the supreme leader is perceived as weak, pressure is being exerted to discredit one faction in favour of the other,” adds Fraz Naqvi. “The hardliners belong to the Deobandi school of Sunni Islam. They are against social and educational reforms. They are also against bringing other ethnicities into the political environment. The second group can be described as relatively moderate, though conservative and militant to the core. They are open to reforms”.

In the faction closer to appeasing the international community and reducing the forcefulness of its decisions would be the acting deputy prime minister, Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar, another of the visible faces of Taliban diplomacy, who led the negotiating team in Qatar on the terms of the US withdrawal with the Trump administration. “Baradar has significant domestic credentials but lacks a military power base and would be strongly opposed by Pakistan,” Felbab-Brown writes in his Brookings analysis.

“There are many different factions. The most common way to summarise them is to divide the group into ‘hardliners’ in Kandahar and ‘pragmatists’ in Kabul. But this analysis is inaccurate, and the many divisions within the movement do not always correspond to residence in Kabul or Kandahar,” Smith stresses. “Some Taliban officials in the capital are understood to be more politically aligned with Kandahar, including senior figures in the Academy of Sciences, the Ministry of Justice, the Supreme Court, the Ministry of Hajj and Endowments, the General Intelligence Directorate and the re-established Ministry for the Propagation of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice in Afghanistan. It is a complicated picture, and outsiders have a poor track record of offering assessments of Taliban policy that have any predictive value.”

“There are differences within the Taliban, given how decentralised and fragmented the group has been operationally over the past two decades,” Sharan explains. “However, these differences are not what many Western policymakers have labelled as a split between moderates and ultraconservatives”.

“We should not forget that the core Taliban leadership is cut from the same cloth and has a clear mission: to purify and radicalise Afghan society and to expand its cause beyond Afghanistan’s borders. These differences are more about strategy than mission. The so-called pragmatists will never go against their emir,” warns the associate professor at Oxford University’s Global Security Programme in conversation with Atalayar, who also classifies these groups as “pragmatists and dogmatists” and points out that “the difference today is more about strategy and priorities than the goal of Islamising and radically transforming Afghan society and, if possible, expanding their mission beyond their borders”.

The Amu TV news channel, run by independent Afghan journalists in exile in the US and Canada, has reported that the group’s leadership stands on three legs. A triumvirate of sorts, comprising the supreme leader, Habitullah Akhundzada, and his two deputy emirs who raised their voices against him, Sirajuddin Haqqani and Mohammad Yaqoob Mujahid. There are no signs of a coup d’état. Especially since Haqqani has seen his power wane in recent weeks. “The supreme leader has curtailed the authority of the interior minister and appointed two influential but loyal people who have the authority to implement his orders even if Haqqani disagrees,” reports EFE, citing a source close to the Taliban government.

In the abyss

Akhundzada has insisted over the past year and a half that he would not allow outside interference. On several occasions he has warned of the existence of members of the movement who are not really Taliban. “Look within [your] ranks and see if there is any unknown entity working against the will of the government, which must be eradicated as soon as possible.” It is not unreasonable that he could unleash an internal war to sweep out critics.

Naqvi recalls in this regard that the Taliban have failed to resolve their internal differences. “Regional relations remain strained, as terrorists using Afghan soil have not been stopped. International recognition remains absent. Working relations with other states remain poor. Women’s education, the failed economic system and other social environments remained poor,” adds the Pakistani analyst.

“The Afghanistan of 2023 will depend on whether or not Taliban supreme leader Haibatullah Akhundzada maintains his iron grip on decision-making,” Felbab-Brown stresses. “Orchestrating an apparent internal coup d’état is extremely risky, as it entails the possible execution of its organisers and the splitting of the Taliban. A coup would require a basic unity of action between Baradar, Siraj [Haqqani] and Yaqub – none of whom trust each other – and the co-option of several other key Taliban military commanders. Today, the likelihood remains small,” she says.

Smith reminds us, however, that the Taliban have more control over Afghanistan’s territory than any other group since the 1970s. “Very few parts of the country are outside their military control. “The north and northeast of Afghanistan, in particular, remain outside their control, where Ahmed Massoud is present and ISIS has its footprints, respectively,” adds Fraz Naqvi, who believes that Afghanistan “is heading towards a chaotic situation, if not open civil war”.

“Women and minorities will remain vulnerable and deprived of their basic rights. Poverty levels look set to rise further, especially if the Taliban’s confrontation with the Western world continues. Famine outbreaks are a serious risk, especially in the Central Highlands and other places where crops are scarce. It will remain one of the world’s biggest humanitarian catastrophes, at least in the short term,” predicts the International Crisis Group consultant.

In any scenario, knowing what is happening in Afghanistan is important because, as Sharan stresses in conversation with Atalayar, “the sooner we realise and recognise the Taliban’s mission in governance, the sooner we can focus on forms of engagement that are more likely to succeed”. “In efforts to improve the situation in Afghanistan, the international community may find allies on some issues among the Taliban, but it is better to keep our eyes open and be realistic about both the values and influence of these allies,” he says.