China’s Expanding Tech Lead Through Digital Silk Road – Analysis

In 2015, China launched the Digital Silk Road (DSR) as part of President Xi Jinping’s flagship transnational infrastructural project, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). While the first two components of the BRI—the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21stcentury Maritime Silk Road, included infrastructure and housing projects, economic corridors, energy exploration programmes, and renewable energy generation projects, DSR delineated Beijing’s approach to expanding information exchanges and digital cooperation with the emerging markets and developing economies.

Eight years after its launch, DSR is challenging West’s tech dominance in the developing world. A tandem of private actors and state-owned enterprises from China, supported by the state banks, have offered inexpensive technological contracts and speedily built digital infrastructure projects. The initiative has picked up pace in recent years as many countries look to harness information and communication technologies for national transformation and economic development. So far, 27 countries in the Indo-Pacific have signed bilateral agreements with China for strengthening digital cooperation under DSR.

This article examines three major activities under DSR—laying undersea cables, installing hi-tech security cameras, and building of 5G network—to understand how China has consolidated its hold in the Indo-Pacific’s digital domain.

Pushing DSR through bilateral engagement

The National Development and Reform Commission’s (NDRC) “Vision and Actions on Jointly Building Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st-Century Maritime Silk Road” document of March 2015 first mentioned the idea of DSR. It stated that China should “build bilateral cross-border optical cable networks”, “plan transcontinental submarine optical cable projects”, and improve “satellite information passageways” to create the “Information Silk Road.” Some subsequent Chinese government reports also referredto the initiative as the “Belt and Road Digital Economy International Cooperation Initiative”, which intended to leverage digital opportunities and enhance connectivity along the ancient Silk Route.

Under the DSR initiative, China has actively encouraged its tech and communication companies to expand cooperation and market share with the recipient countries. Fittingly, many state-owned enterprises like China Telecom, and Unicom, along with private companies like China Mobile, Huawei, Beidou, Hengtong, Alibaba, Tencent, Hikvision, Dahua, and others, have consolidated their presence in the emerging markets and developing economies in the Indo-Pacific. While seeking to createdomestic technological capabilities through the DSR, China has also attempted to model itself as the central connecting node, facilitating the expansion of Chinese tech corporations, accessing large data pools and developing a new standards ecosystem.

A large part of DSR’s expansion has happened through the number of bilateral digital cooperation agreements that China signed with 27 countries in the Indo-Pacific. Under these agreements, China has built Information and Communications Technology (ICT) infrastructure, laid undersea cable networks, and facilitated 4G and 5G connectivity to increase connectivity within the Indo-Pacific.

Between 2013 and 2018, China invested close to US$ 55 billion in building ICT infrastructure in these countries through loans (concessional and non-concessional), lines of credit, and grants. Companies like Huawei and Alibaba have played a significant role in this engagement. For instance, Huawei has emerged as the primary vendor for any 5G-related technological development within the Indo-Pacific.

China’s web of undersea cables

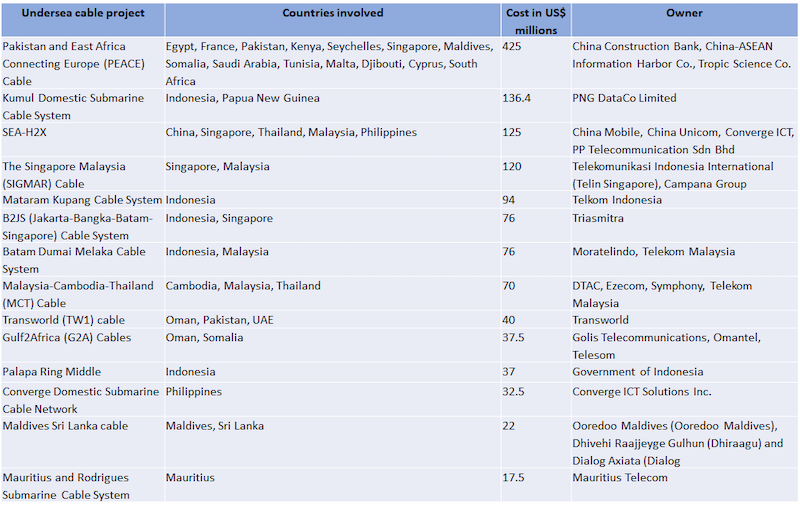

Table 1: Major Undersea Cables built by HMN Technologies

As the data above suggests, China’s HMN Technologies (formerly Huawei Marine Networks) has executed 16 undersea cable projects covering about 27 countries in the Indo-Pacific. The total cost of these projects is US$ 1.6 billion. Most notably, these projects have had considerable Chinese state patronage, enabling HMN Technologies to expand its footprint steadfastly. From holding merely a 7-percent share of total undersea cables projects in 2012, the company increased its share to 20 percent in 2019. In 2020, Hengtong, China’s largest power and optical fibre cable manufacturer, acquired an 81-percent stake in HMN Technologies. One of its major recent projects is the ambitious PEACE undersea cable which starts in Pakistan and ends in France, connecting Europe, Africa, and Asia. It bypasses India.

The cable has raised concerns regarding user privacy and data protection in the United States (US). These concerns stem from China’s National Intelligence Law, 2017, which mandates Chinese organisations and citizens to “support, assist, and cooperate with the state intelligence work.” This includes handing over or giving access to user data or any information pertaining to national security or any other dataset the Chinese tech companies have trafficked. This has prompted speculations of the presence of digital ‘backdoors’ in digital infrastructure by Chinese companies at Beijing’s behest.

CCTV cameras and surveillance risk

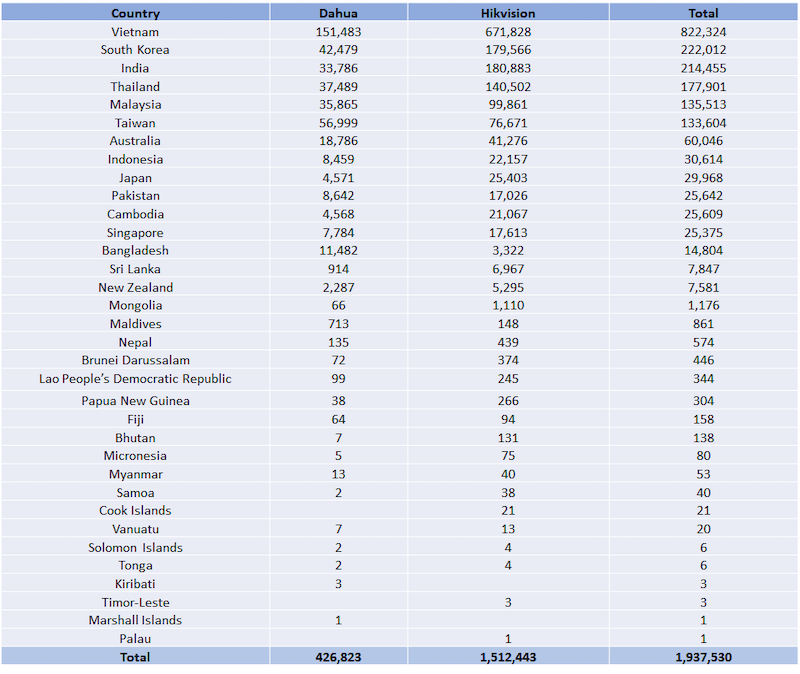

Chinese companies have also gradually strengthened their presence in the global CCTV market. The two largest CCTV companies in the world are Chinese—Hikvision and Dahua, which have installed more than 6.3 million cameras outside China: 25 percentare in the US and Vietnam.

Table 2: CCTV Cameras installed by Dahua and Hikvision in the Indo-Pacific

Many of these CCTV cameras have been installed by national authorities as part of ‘smart city’ solutions offered by China under the BRI. Notably, these two companies have also installed approximately 2.14 lakh CCTV cameras in various Indian cities, including Mumbai (32,563), Chennai (9,795), Bengaluru (8,616), and Delhi (7,006).

Like the undersea cables, these CCTV cameras have also aggravated surveillance concerns. Australia, for instance, has begun removing Hikvision and Dahua cameras after a government audit found these cameras at government buildings. The US and Australia have also directly linked the two companies to the Chinese authorities’ surveillance in the restive Xinjiang province. Incidentally, Hikvision, in 2020, in its half-year report, noted that it is financing surveillance equipment worth US$ 145 million for Xinjiang police. Other reports have pointed out remote hijacking vulnerabilities in the Hikvision cameras, which may enable unauthorised access. Again, this has sparked concerns about cross-border data transmission to Chinese servers. These concerns led the US government to ban Dahua and Hikvision sales on American territory in 2022 and to reassess surveillance tech used at government facilities.

Emerging threats from 5G network

China is playing a leading role in 5G deployment, research, and innovation. Chinese companies such as ZTE, Huawei, and China Unicom have been aggressively penetratingnew markets by commercialising the technology and offering it at cheaper rates than their competitors. This, combined with the aggressive government push, has enabled Huawei and ZTE to corner 29 and 11 percent of the global 5G market. This expansion has raised worries that China may strategically push these companies to capture newer markets and establish an eavesdropping network.

China aims to extend this market dominance by conceptualising the 5G standards. The Chinese narrative is that it wishes to technologically equip the developing world for the next industrial revolution (of which 5G is a vital component). Developing new tech standards is critical for China to provide the international influence it seeks and to yield monetary remuneration. In some instances, it has already benefitted. Huawei alone, for example, brought in US$ 3 billion worth of licensing royalties between 2019-2021. Another significant aspect of the standardisation race is the new internet protocol that China proposed through Huawei’s presentation at the Internet World Conference in 2021. This new package aims to replace the US-invented Transmission Control Protocol/Internet Protocol (IP). Although the newly proposed IP standard is faster than the existing protocol, it has built-in surveillance and a “shut-up command,” which can cut data flowing to and from any IP address at any given time.

Conclusion

Through DSR, Beijing has been able to erect a parallel tech empire that challenges the West’s tech dominance. While the initiative has the potential to enhance digital connectivity in developing economies of the Indo-Pacific, it also provides Beijing with a tool that it can leverage by way of surveillance and exploitation of in-built backdoors to suit its geopolitical objectives. This weaponisation of tech through DSR has direct implications for the democracies in the Indo-Pacific.