ISIS Strikes Moscow

What happened?

On the evening of 22 March, militants mounted a harrowing attack on Crocus City Hall, a music venue in the suburbs of Moscow, taking at least 139 lives. Surveillance camera footage from inside the building shows the assailants firing ruthlessly upon concert attendees with light automatic weapons, adding to the chaos by setting the premises ablaze. The arson caused many of the deaths, with people dying of burns and smoke inhalation, and enabled the attackers to get away from the scene.

That same night, the Islamic State (ISIS) claimed responsibility for the attack through its official channels on Telegram, the social media platform favoured by the group. It first released a concise statement acknowledging the incident and noting the perpetrators’ escape. It then issued a more detailed communiqué the next day, featuring blurred pictures of the assailants. Therein ISIS expounded on its reasons for staging the assault: the victims were Christians and killing them was part of the group’s conflict with “the states that fight Islam”.

The U.S. has confirmed that it holds ISIS responsible. It also said it had warned Russian authorities two weeks prior that an attack could be imminent and advised U.S. citizens to avoid large gatherings that the group could target. The Crocus City Hall assault occurred two weeks after the Russian security services said they had prevented a similar attack on a Moscow synagogue.

The Russian authorities swiftly announced a string of arrests, including of four Tajik citizens whom it suspects of being the perpetrators. Four other individuals were also detained. On 24 March, the four suspected shooters appeared in a Moscow court, bearing visible signs of abuse. Videos had already circulated online depicting the torture of one suspect with electric shocks and the brutal severing of another’s ear, which Russian security personnel then forced the man to eat.

Why did ISIS attack Russia?

Since 2019, ISIS has become much weaker in its former strongholds in Iraq and Syria, where in 2014-2016 it controlled vast tracts of land. The group has lost its territorial seat and its main leaders. It still stages attacks in eastern Syria, but its current chief may not be based there, according to Western security sources – his whereabouts are unknown. ISIS has survived as a global organisation largely by expanding into other countries. It now consists mostly of a network of affiliates operating around the world, notably in the Sahel and north-eastern Nigeria, as well as in East and Central Africa. These affiliates have primarily local goals, carving out “provinces” of the would-be ISIS caliphate, but some also pose threats in the wider regions in which they operate.

ISIS has targeted both Western and Middle Eastern countries since proclaiming its “caliphate” in 2014. The group’s prominent attacks in the West include the November 2015 strikes in Paris, which killed 131 people, and the March 2016 assaults in Brussels, which took 32 lives. It has, more recently, launched three attacks in Iran, including a shooting at a major Shiite shrine in Shiraz in 2023. It also carried out twin bombings in the city of Kerman in January, killing 94. The same month, it hit the Santa Maria church in Türkiye, claiming another life. Turkish authorities arrested the perpetrators of the church assault, identifying them as part of the same cell that planted the bombs in Kerman.

Russia is an obvious target for historical and contemporary reasons. ISIS does not generally differentiate among the countries of the world, considering them all legitimate targets because they are either inhabited by non-Muslims or ruled by apostates. But Russia inspires a special animosity. The Soviet Union’s invasion of Afghanistan in 1979, and the subsequent decade of occupation, still arouse fury among many jihadists, as do Russia’s two domestic wars in Chechnya in 1994 and 2000. More recently, Moscow’s active engagement in support of the Syrian regime involved numerous clashes with ISIS, notably in the city of Palmyra, which Russian airpower helped regime forces recapture. Over the past year, Russia has also nurtured alliances with juntas in the Sahel, backing them in efforts to rein in various militant groups, including the ISIS affiliate in the region. In October 2015, an ISIS franchise in the Sinai Peninsula claimed responsibility for the bombing of a Russian civilian plane that blew up after departing from Sharm al-Sheikh airport in Egypt.

Was the ISIS affiliate in Afghanistan involved in the Moscow attack? What is the role of the Taliban?

Western officials tend to see the Islamic State-Khorasan Province (IS-KP), based in Afghanistan and Pakistan, as the affiliate most capable of perpetrating attacks outside its immediate area of operation. In the case of the Moscow attack, the main ISIS organisation – not IS-KP – took responsibility, but sources suggest that the U.S., which has publicly blamed the global outfit rather than its Afghanistan affiliate, does see IS-KP as involved. (Among other recent attacks, IS-KP claimed the one in Shiraz, whereas the global organisation assumed responsibility for the Kerman bombings, though the Turkish security services, which apprehended the suspects, say they are likely to belong to IS-KP.) A Russian official monitoring ISIS told Crisis Group that the cell responsible for the Crocus City Hall massacre was likely part of the global network. Regardless, it is quite possible that the plotters of ISIS attacks outside the Middle East have close connections to IS-KP.

IS-KP emerged in 2015, around the time that the ISIS “caliphate” in Iraq and Syria reached its peak. At first, the group consisted of a system of alliances among insurgents previously aligned with the Pakistani Taliban, disenchanted Afghan Taliban commanders and assorted Central Asian militants, although it later bolstered its ranks by recruiting from among urban youth. The group had ups and downs over the years, up to the withdrawal of U.S. forces in August 2021, when it staged a devastating attack on the Kabul airport, killing 150 civilians as well as thirteen U.S. soldiers. The Taliban have fought IS-KP since its inception, seeing it as a dangerous adversary.

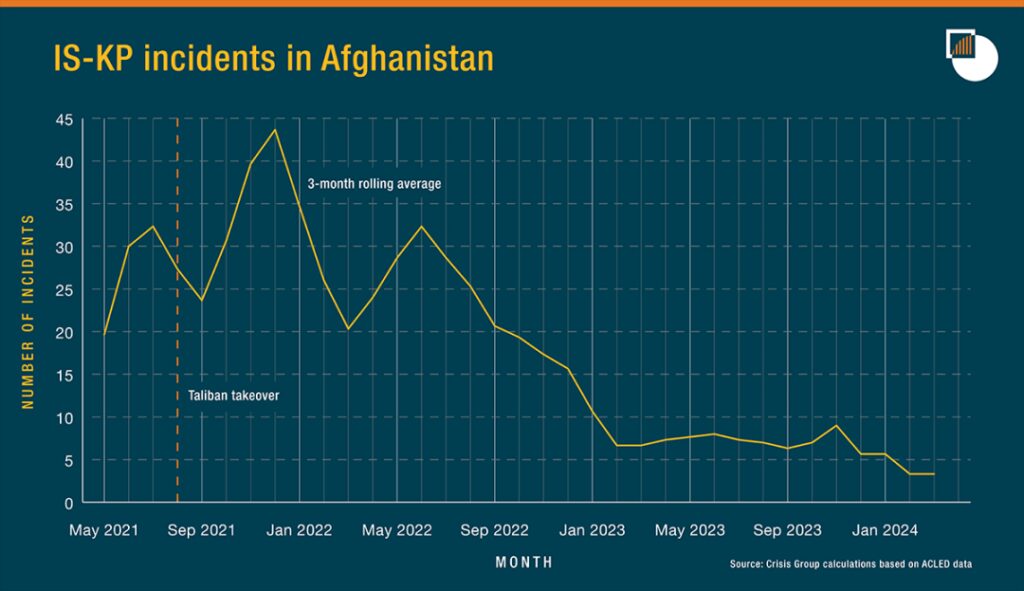

Since the Taliban took over Afghanistan following the U.S. departure, IS-KP has carried out several attacks outside the country. One catalyst for IS-KP’s increasing forays abroad is its increasing displacement from its Afghan strongholds. The Taliban struggled at first to contain IS-KP, but in the last two years, they have put considerable military pressure on the group. Meanwhile, IS-KP has been largely unable to loosen the Taliban’s grip, even in its heartlands near the Pakistani border. The number of IS-KP attacks in Afghanistan has significantly declined (Figure 1), though as recent killings of minorities and a suicide bombing in Kandahar show, the group remains potent. Mounting attacks in foreign countries serve as a means of projecting power and preserving IS-KP’s relevancy, even as the group loses fighters and territory in Afghanistan.

Militants from Central Asian countries have carried out many of IS-KP’s major foreign attacks, suggesting a growing symbiosis between IS-KP and ISIS networks in Central Asia and Russia, including Chechnya. Central Asians and Chechens are prominent among those arrested or involved in attacks in Iran, Türkiye and now Russia, as well as numerous other plots uncovered in Western Europe. Central Asians and North Caucasians played significant roles in the Syrian conflict, with various factions – including ISIS – actively recruiting among those populations. While many in the ISIS ranks had died by 2019, when the organisation lost its last pocket of territory in Syria, others were detained or managed to leave the country. Türkiye was a stopover for many of these escapees, as is reflected in numerous arrests there over the past year. Leveraging connections forged in Syria, these ex-fighters cultivate contacts across the region, facilitating coordination of additional attacks.

In Afghanistan, outside powers tend to view the Taliban as a bulwark against IS-KP, but regional countries still express serious concerns about IS-KP threats. In February, the UN Sanctions Monitoring Team, whose reports on the Islamic State and al-Qaeda are influenced by regional security officials, noted that the Taliban had taken action against IS-KP and were trying to tamp down the activity of other militant groups, but with mixed results. It said IS-KP’s ability to operate inside Afghanistan has been constrained but that the group retained capacity for external operations, especially based on its growing appeal among ethnic Tajiks. The UN report claimed, and Crisis Group interlocutors have confirmed, that the Taliban’s successes reining in IS-KP were partly due to Taliban efforts to infiltrate the group. As Crisis Group has recently outlined, Russia and other countries have been holding informal dialogues with Taliban officials, partly aimed at better understanding IS-KP. The impact of the Moscow attack on these contacts is unclear as yet. At the same time, Tajikistan – the Central Asian state with the thorniest relations with the Taliban – has proposed a “security belt” to contain threats from inside Afghanistan with support from the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, a group that includes nine regional countries including Russia and China. The Taliban recently asked to join the Organisation’s future meetings, in part for the sake of discussing security issues.

What threat does IS-KP pose to other countries, including in Europe?

IS-KP, including its Central Asian and Russian networks, is the primary militant threat on the radar of Western Europe, according to European security sources. General Michael Kurilla, the head of U.S. Central Command, notably predicted in early March that IS-KP was trying to conduct external attacks “in as little as six months and with little to no warning”. Privately, European security sources offer a more nuanced perspective, debating whether recent plots in Europe were orchestrated by IS-KP itself or merely inspired by it. The latter type of plots tend to involve individuals, often though not always from marginalised communities, who come into contact with IS-KP militants through social media, leading to their recruitment. But these sources also say large-scale coordinated assaults are possible. France, which is hosting the 2024 Summer Olympic Games, is particularly worried about IS-KP.

IS-KP also differs significantly from past threats. In 2015-2016, ISIS administered large parts of Iraq and Syria. The group’s territorial control was key to enlisting European citizens from abroad, training them in Syria and sending them back to carry out attacks. The recruits then benefited from networks of friends and acquaintances, who helped them hide, gather weapons and stage assaults in places that were known to them, heightening the impact of attacks. IS-KP occupies no territory in Afghanistan, and it has been unable to attract a significant number of Western recruits, meaning that it would have great difficulty replicating the success of ISIS’s attacks in Europe in 2015-2016. Those it does recruit face growing obstacles in travelling to Afghanistan for training, further limiting its reach and operational capabilities.

The U.S. appears to have been able to garner intelligence on ISIS. In 2024, for instance, it has issued cautionary advisories not just to Russia but also to Iran ahead of the attacks in those two countries, though these did not prevent either incident. In the case of Russia, distrust between the two countries against the backdrop of the war in Ukraine seemed to play a major role. Days before the attack outside Moscow, speaking to the Federal Security Service (FSB), Russia’s principal intelligence agency, Putin dismissed the warnings as provocative and aimed at destabilising Russia. After the attack, Russian officials argued that the U.S. advisories contained no specific information. Meanwhile, leveraging its substantial capabilities, particularly in monitoring social media, the U.S. has disseminated a growing amount of critical intelligence to other Western countries, leading to many arrests.

Are the Moscow attacks connected to Russia’s war in Ukraine?

While there is no reason to think that the ISIS attack has any link to Ukraine, the FSB suggested just that, almost immediately afterward, and President Vladimir Putin has publicly supported the accusation. Without presenting evidence (besides that the motorway on which the suspects were arrested eventually leads to Ukraine), he said the four men Russia believes were the shooters were trying to flee via a “window” on the Russian-Ukrainian border. A spokesman for Ukrainian military intelligence quickly pointed out the absurdity of this allegation, given that the suspects would have had to cross an active front teeming with Russian soldiers and secret police. The attack, in any case, seems out of sync with Ukraine’s tactics in defending itself from Russia’s all-out invasion. Ukraine has the capacity to attack Russia’s rear with missile and drone strikes, and it has done so, including on the night after the massacre at Crocus City Hall. Ukrainian security services are behind assassinations of war propagandists in Russia and Ukrainians collaborating with the Kremlin. But Ukraine has never resorted to purposeful large-scale attacks on civilians such as those ISIS and its affiliates have conducted. Although such attacks might cause turmoil in Russia, thus serving Ukrainian interests amid the war, the reputational risks for Kyiv of associating itself with jihadist movements would be devastating. Any such connection would further compromise Kyiv’s chances of obtaining more vital but increasingly hard-to-get Western military aid.

Russia has continued to accuse Ukraine of involvement in the Crocus City Hall attack without presenting credible evidence. On 25 March, Putin suggested that Islamist militants were the gunmen but insinuated that the masterminds could have been sitting in Ukraine or the West. The following day, Nikolai Patrushev, secretary of Russia’s Security Council, asserted that Ukraine, rather than ISIS, was to blame. FSB head Aleksandr Bortnikov also claimed that Ukraine had been planning to greet the fleeing perpetrators as heroes. In support of these arguments, Russian security services point to Ukrainian security services’ history of recruiting people from the North Caucasus into the ranks of the International Legion, as various units fighting on Kyiv’s behalf are collectively known. In 2022 and 2023, the FSB and Russian foreign intelligence accused Ukraine of enlisting former ISIS combatants to fight Russia as part of the Legion. In fact, some Legion members, including a number of Chechens, did battle the regime in Syria alongside Syrian opposition groups and former ISIS members, although not under the banner of ISIS. Russian media has also reported that the Ukrainian embassy in Tajikistan was involved in recruitment efforts for the International Legion.

Such accusations could lay groundwork for the Kremlin to justify future aggression in Ukraine, perhaps including attempts to assassinate Ukrainian government officials. FSB chief Bortnikov has hinted at the possibility of killing the head of Ukrainian military intelligence, Kyrylo Budanov.

What implications might the attack have for Russia domestically?

Within Russia, the attack is likely to further strengthen the Kremlin’s hand. The Kremlin may also use it as justification for further crackdowns on opposition figures and restrictions on local governance and civil liberties. There is precedent: Putin abolished direct election of governors in response to the 2004 Beslan attack, when gunmen besieged a school, leading to hundreds of deaths, 186 of them among the young pupils. The Kremlin, which has been rolling back civil liberties since the 2000s, has limited scope for more such actions, except probably the imposition of martial law. That said, members of Parliament have reacted to the Crocus City Hall massacre by demanding changes to the Russian constitution to lift the moratorium on the death penalty for those accused of terrorism. Because Russia accuses a great many political dissidents of terrorism when it brings them to trial, this measure could be ominous if it moves forward. Meanwhile, the footage of the tortured suspects further lowers the bar for what passes as normal conduct by authorities in Russia and Ukraine’s occupied territories.