The Techo Funan Canal Won’t End Cambodia’s Dependency On Vietnam – Analysis

First it was the Ream Naval Base. Now it’s the Techo Funan Canal.

Could the planned $1.7-billion waterway that will cut through eastern Cambodia – which will be built, funded and owned by a Chinese state firm – be used by Beijing to attack or threaten Vietnam?

Phnom Penh denies this and Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Manet reportedly had to assuage the Vietnamese leadership of this concern during a visit last December.

Sun Chanthol, a Cambodian deputy prime minister and the former minister of public works, recently said he also tried to mollify Hanoi’s concerns about the project, formally known as the Tonle Bassac Navigation Road and Logistics System Project.

The United States has been more vocal than Vietnam in raising concerns over the Ream Naval Base in southern Cambodia, which China is extensively refurbishing and where China appears to have stationed some vessels for the past few months.

But Hanoi’s worries about the Techo Funan Canal have leaked out in drabs from within Vietnam.

Last month, an academic journal article by two researchers at the Oriental Research Development Institute, part of the state-run Union of Science and Technology Associations, warned that the Cambodian canal might be a “dual-use” project.

“The locks on the Funan Techo Canal can create the necessary water depths for military vessels to enter from the Gulf of Thailand, or from Ream Naval Base, and travel deep into Cambodia and approach the [Cambodia-Vietnam] border,” they argued in a study that was republished on the website of the People’s Public Security Political Academy.

Geopolitical implications

One ought to be skeptical. China having access to the Ream Naval Base is one thing— it is a military base. It makes sense for Beijing to want to station and refuel its vessels on the Gulf of Thailand, effectively encircling Vietnam.

But if China was thinking of attacking Vietnam, wouldn’t it be simpler for the Chinese navy to follow Cambodia’s coastline to Vietnam? Beijing presumably wouldn’t want its vessels to be stuck in a relatively narrow Cambodian canal.

But if you can imagine Cambodia allowing the Chinese military access to its inland waterways to invade Vietnam, why not imagine Phnom Penh allowing the Chinese military to zip along its (Chinese-built) expressways and railways to invade Vietnam?

If you are of that mindset, then Cambodia’s road or rail networks are just as much of a threat, or perhaps more so, as Cambodia’s naval bases or canals.

Nonetheless, the canal has geopolitical implications for Vietnam.

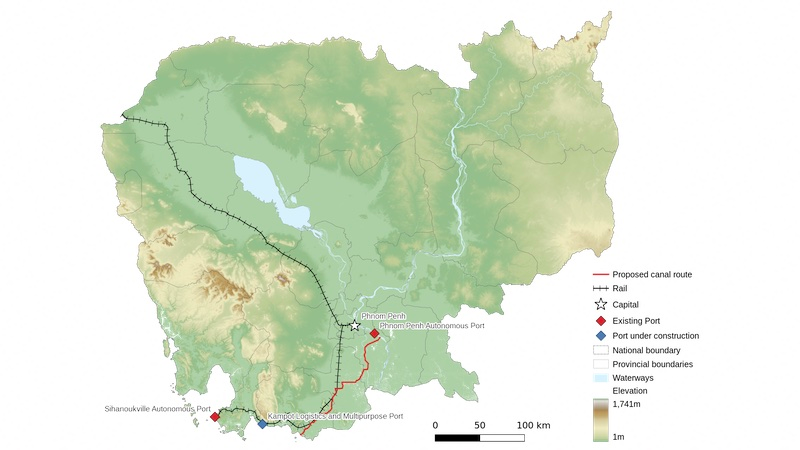

Cambodia exports and imports many of its goods through Vietnamese ports, mainly Cai Mep. The Funan Techo Canal, by connecting the Phnom Penh Autonomous Port to a planned deepwater port in Kep province and an already-built deep seaport in Sihanoukville province, would mean that much of Cambodia’s trade no longer needs to go through Vietnam.

Phnom Penh can justifiably say this is a matter of economic self-sufficiency. “Breathing through our own nose,” as Hun Manet put it. Phnom Penh reckons the canal will cut shipping costs by a third.

Cambodia has a dependency on Vietnam’s ports. If Cambodia-Vietnam relations turned really sour, such as Phnom Penh giving the Chinese military access to its land, Hanoi could close off Cambodia’s access to its ports or threaten to do so, effectively blocking much of Cambodian trade – like it did briefly in 1994.

Remove that dependency, and Vietnam has less leverage over Phnom Penh’s decision making.

Mekong River projects

Even the environmental concerns around the canal are about geopolitical leverage.

Vietnam is justified in fearing that Cambodia altering the course of the Mekong River—after Laos has been doing so for two decades—will affect its own already at-risk ecology.

Fears are compounded by the lack of publicly available environmental impact assessments over the canal and the fact that the Mekong River Commission, a regional oversight body that is supposed to assess the environmental impact of these riparian projects, has become a feckless body for dialogue.

Hanoi is no doubt concerned about its own position since it hasn’t been able to get Phnom Penh to openly publish those impact assessments. This further compounds Vietnam’s sense of weakness for having failed for more than a decade to limit how its neighbors go about altering their sections of the Mekong River, with highly deleterious impacts on Vietnam’s environment and agricultural heartlands.

Clearly, Phnom Penh isn’t for turning on the canal project. Just this week, Hun Manet applauded apparent public support for the scheme as a “huge force of nationalism”. Phnom Penh is making this a sovereignty issue, thus making criticism a matter of state interference, a way of silencing dissent in Southeast Asia.

It’s not all bad news for Vietnam, though. The Financial Times notedthat, according to Vietnamese analysts, even if the Techo Funan Canal goes ahead, “Hanoi retains leverage over Cambodia” because ships carrying more than 1,000 tonnes would still rely on Vietnamese ports.

Cambodia could get around this by using smaller vessels. That would be less profitable but still doable. By my calculation, Cambodia’s exports to Vietnam have grown by more than 800% over the last six years, from $324 million in 2018 to $2.97 billion last year.

In the first quarter of this year, Vietnam bought 22 percent of Cambodia’s goods. Exports certainly give leverage. No other single country is queuing up to start buying a fifth of Cambodia’s products.

Trade dependency

In fact many of these Cambodian exports are re-exported by Vietnam to China, so Phnom Penh might think it can cut out the Vietnamese middleman. But it cannot.

Arguably, Cambodia’s biggest dependency on Vietnam is that Cambodia’s economy increasingly must become integrated into Vietnam’s supply chains.

Look around Southeast Asia in the coming decade: Laos has hydropower; Thailand has automobile manufacturing; Malaysia has semiconductor chips; the Philippines has its green economy schemes; and Indonesia has natural resources and electric vehicle batteries. The region is carving itself out into niches.

But Cambodia seems somewhat stuck with low value-added garment production, some agricultural growth and tourism – sectors that depend on the health of the Chinese economy. Cambodia’s construction sector, which drove much of the growth of the past decade, is likely to struggle as a result of that sector’s meltdown in China.

Despite all the grand promises of Phnom Penh’s Pentagonal Strategy, a 25-year-plan to make Cambodia a high-income country, it’s hard to see the country massively improving its labor productivity, which is one of the worst in Southeast Asia.

That means Cambodia cannot really rival its neighbors in higher-end, higher-value-added industries. And Cambodian labor isn’t that low cost anymore, and with a population much smaller than its competitors, it’s at a scale disadvantage.

This all leaves Cambodia dependent on serving Vietnam’s supply chains.