ISKP’s Latest Campaign: Expanded Propaganda and External Operations

Introduction

The Islamic State Khurasan Province’s (ISKP) capabilities and intent to carry out attacks outside of its nucleus in Pakistan and Afghanistan are increasing. After a recent flurry of activity, ISKP has conducted several successful operations, including a bombing in Iran that took the lives of nearly 100 people in early January and a sophisticated attack in Moscow that claimed the lives of 145 people while injuring another 551.

The threat was underscored yet again, most recently with the May 31 arrest of an 18-year-old Chechen man — who was communicating with ISKP — in France’s Saint-Etienne region for an alleged plot to attack spectators and security staff during the upcoming Paris Olympics. This follows months of propaganda specifically calling for terrorism against sporting events in Germany, France, Spain, the United States and more.

Most branches of the Islamic State (IS) are focused on their specific region or Wilayah, while ISKP is setting its sights beyond its borders as it works to expand its external operations attack network, not just in South and Central Asia but also in the West and beyond. There has been a notable surge in ISKP’s external activities since mid-December. In addition to the attacks in Iran and Russia, ISKP was involved in an attack in Turkey and reportedly Tajikistan, alongside plots foiled in Austria, Germany, Kyrgyzstan, and Russia.

Since the Taliban’s takeover of Afghanistan in August 2021, ISKP has been developing a strategy of regionalisation and internationalisation. The branch has broadened its propaganda outreach efforts to build support throughout South and Central Asia while also producing materials in several other languages to reach audiences and diaspora communities well beyond its traditional base territory. This is coupled with an interlinked militant campaign to target foreign interests inside Afghanistan, as well as to direct operations and incite followers in the region and globally, particularly in the West, to violence. Its fundraising and recruitment networks are likewise increasingly transnational.

This Insight will analyse ISKP’s expansive media and communications network alongside the group’s role in facilitating and carrying out the Islamic State’s international attack operations.

Media Jihad, Technology Use, and Media Partnerships

ISKP has thoroughly embraced the Islamic State’s longstanding organisational culture regarding “media jihad” and has innovatively worked it into its own objectives and mission. This is apparent in the resources the group devotes to its propaganda activities while also linking up with various other outside pro-IS propaganda producers. In an article titled ‘Strengthen the Media War,’ in issue 23 of its flagship Voice of Khurasan magazine, the group stresses the importance of propaganda throughout Islamic history and how it continues to be crucial in growing support for the cause and countering the narratives of the Taliban and other primary enemies. As part of this, ISKP encourages its supporters to create propaganda, amplifying its messaging independently.

In addition, ISKP’s Al-Azaim has expanded its collaboration with external propaganda producers and developed into an entity that provides materials in the most languages to the rising pro-Islamic State archive and translation platform called I’lam Foundation, which has surface-level web addresses and is likewise available on the Dark Web. While ISKP solidifies its in-house propaganda apparatus, these external partnerships add extra production capacity and reach to its messaging.

Al-Azaim is the biggest contributor to a significantly larger constellation of IS-affiliated media. Currently, sixteen translation groups fall under the Fursan al-Tarjuma umbrella and produce translations and propaganda in English, French, Somali, Swahili, Pashto, Urdu, Turkish, Spanish, Azeri, Hausa, Bengali, Hindi, Farsi, Uzbek, Tajik, Russian, Dhivehi, Kurdish, and Albanian.

ISKP’s Al-Azaim began forging connections with members of Fursan al-Tarjuma in 2022. Around this same time, there started to be frequent signs of collaboration between Al-Azaim and the Halummu — an English IS translation group — when the two started collaborating on English language translations of IS’s weekly al-Naba newsletter. In November 2022, Halummu was the first to tease an upcoming issue of ISKP’s English publication, Voice of Khurasan (VoK). In the issue, VoK included an infographic produced by Halummu. Moreover, ISKP’s Al-Azaim has forged relations with the Arabic pro-IS propaganda outlet At-Taqwa, featuring its work in its magazines. ISKP has also formed partnerships with the pro-IS outlets Al-Adiyat, Talaa al-Ansar, and others.

Expanded Propaganda Scope

ISKP has leveraged its propaganda infrastructure to enact a regionalisation and internationalisation strategy, centralise its messaging through the Al-Azaim Foundation for Media Production, and ramp up its criticisms, threats, and calls for attacks against a widened range of countries, both in the region and abroad. ISKP propaganda often focuses on inspiring attacks by supporters abroad but has also revealed priorities for the group’s directed attacks.

Al-Azaim for Media Production emerged as the premier production house from an ecosystem of competing but aligned propaganda outlets, beginning with a scope limited to mostly religious topics and then expanding to cover an ambitious range of political, social, and military issues at the regional and global levels. ISKP’s content is published in Pashto, Dari, Arabic, Urdu, Farsi, Uzbek, Tajik, Turkish, Hindi, Malayalam, Russian, English, and occasionally Uyghur. It produces Pashto, English, Arabic, Tajik, and Turkish online print magazines, as well as videos in several languages. ISKP uses a diverse range of tech platforms to communicate, spread, and store its propaganda, such as Telegram, Facebook, TikTok, Hoop, Element, Archive.org, and more.

The organization has also begun to release Pashto language propaganda bulletins using an artificial news anchor. The AI-generated presenter made his first appearance to claim a May 17 attack in Afghanistan’s Bamiyan province that killed three Spanish tourists and one other person. At the time of writing, the ISKP supportive channel “Khurasan TV” has released four generated videos detailing the activities of the group. Monitors of ISKP propaganda note improvements in the quality of the digital creations.

ISKP’s regionalisation strategy focuses on South and Central Asia as well as Iran.

The branch developed Pashto, Urdu, Tajik, Uzbek, Farsi as well as other language media wings of Al-Azaim. This has enabled ISKP to extend its reach into a broader range of ethno-linguistic population segments by profiling martyrs of a variety of nationalities and ethnicities, increasing its base of support, recruitment, and fundraising. It also uses its propaganda to criticise, threaten, and call upon its supporters to commit violence against countries like Pakistan, India, Iran, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, China, Russia, and Iran to appeal to oppressed or disenfranchised Muslims in these nations. Al-Azaim likewise produces an abundance of materials criticizing the Taliban and its jihadist allies while publicly calling for other militants to defect from their groups and join ISKP.

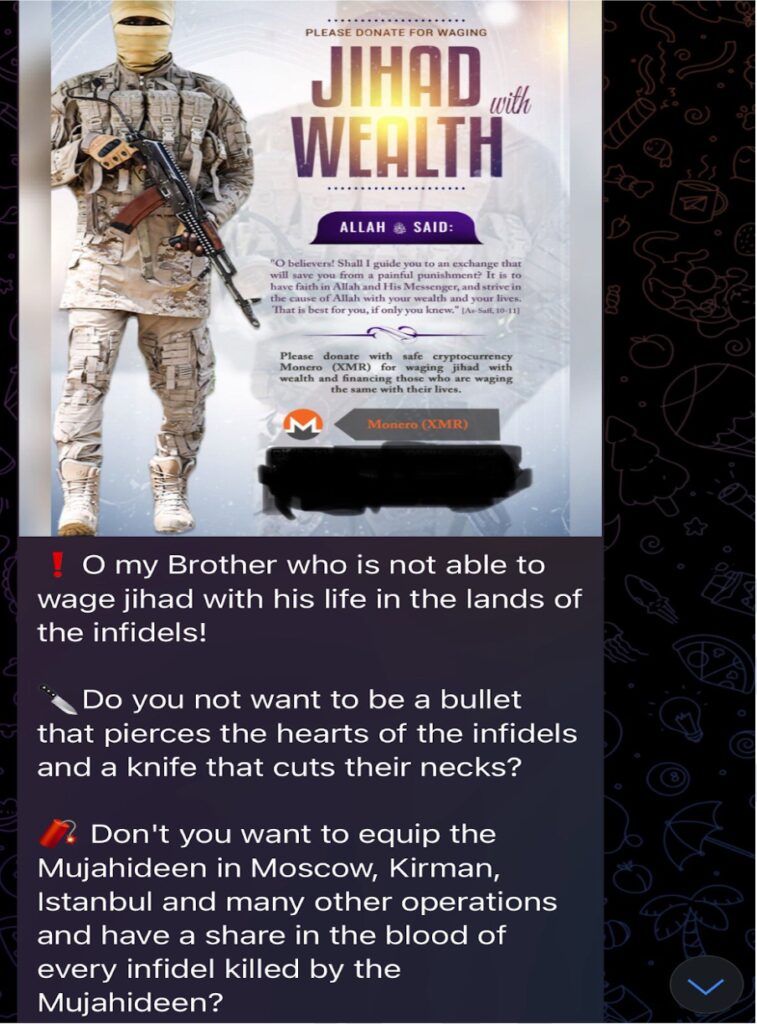

Al-Azaim presents itself as the only vehicle in the region that is actively targeting the nationals and interests of the countries these groups maintain grievances against, contrasting its doctrine with the Taliban, which is pursuing relations with most of these states and restricting groups like the Tajik Jamaat Ansarullah and Uyghur Turkistan Islamic Party from conducting external attacks. ISKP’s financial networks are also international, using fundraising options like cryptocurrency — receiving transfers from IS’s Somalia branch, putting its Monero addresses in materials published in several languages, and fundraising from Islamic State networks in Turkey and others running from Afghanistan to Central Asia, Russia, and Syria, and other avenues. US counter-terrorism operations have managed to disrupt some of these funding channels. In January 2023, a raid against a cave complex in northern Somalia by US forces killed Bilal al-Sudani and 10 other alleged IS operatives. Sudani was a sanctioned Islamic State financier alleged to have provided funding for an attack against an airport in Kabul during the US withdrawal. On 3 April, ISKP posted a request for Monero donations and explicitly said such funds are directly used for external operations like those in Kerman, Istanbul, and Moscow.

Attacks on Foreign Interests in Afghanistan and External Operations Ambitions

ISKP embodies the bellicosity of infamous jihadist Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, the ideological godfather of the Islamic State’s sectarian agenda, and the international incitement and external operations emphasis of Abu Muhammad al-Adnani — they have produced numerous propaganda materials lionising these two. This is imbibed in its militant campaign, as this broadened vision has seen ISKP conduct a suicide bombing against US military forces at Kabul airport in 2021, the 2022 attacks on the Russian and Pakistani embassies, and the murder of Western tourists in May of this year.

ISKP also launched an assault on a hotel in Afghanistan’s capital with the explicit intent of targeting Chinese nationals when a terrorist detonated an explosive vest in January 2023 at the Taliban’s Foreign Ministry building just as a Chinese delegation was scheduled to arrive. A series of bombings also targeted India’s interests in Afghanistan. In 2021, multiple bombings targeted diplomatic personnel, including the Indian consulate in the Afghan city of Jalalabad. Explosions near the consulate killed several Taliban fighters. ISKP claimed responsibility shortly after. In June 2022, ISKP militants attacked the Karta-e-Parwan Gurudwara (Sikh temple) in the Afghan capital city of Kabul in stated retaliation for remarks made by senior BJP (Bhartiya Janta Party) officials about Prophet Mohammad.

To assert itself as one of the Islamic State’s most potent affiliates, ISKP has been expanding its external operational networks and increasing efforts to strike abroad. In addition to its successful attacks inside Iran, the branch has fired rockets into Uzbekistan and Tajikistan and has been implicated in multiple acts of violence in the Maldives. Prior to this, after crossing from Afghanistan in November 2019, 15 ISKP militants were killed and four others arrested in a battle with Tajik security forces near the Tajik-Uzbek frontier. These actions allow ISKP to claim both military and propaganda victories, showing their willingness to take the fight beyond its borders to enemies of the future global caliphate as well as sectarian targets. Infrastructure projects that would connect Afghanistan to more international trade have also become attractive targets. An ISKP Uzbek media wing also threatened to bomb Chinese pipelines running through Central Asia and to kill anyone working on a railway project planned to run from Uzbekistan to Afghanistan to ports in Pakistan, while an aligned channel promised to attack the Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India (TAPI) gas pipeline project.

Other targets of ISKP plots include Iran, India, Turkey, and Qatar, along with successful attacks in the Maldives. In late December, a plan to attack the central square and a church during New Year celebrations in Jalal-Abadin, Kyrgyzstan, by two teenagers directed by ISKP operatives was allegedly prevented by security forces. After the Moscow attack in March, French President Emmanuel Macron said he had information indicating ISKP was behind the attack, adding the group had made multiple attempts to attack France as well.

ISKP has been linked to a growing number of plots in Europe. In March 2024, two Afghan nationals were arrested in Germany for a plot reportedly ordered by ISKP to carry out a mass shooting against law enforcement personnel and civilians near the Swedish parliament in Stockholm, Sweden. Months before this, three men were arrested in the German state of North Rhine-Westphalia over alleged plans to attack the Cologne Cathedral on New Year’s Eve 2023. The raids are linked to another three terror arrests in Austria and one in Germany that took place on December 24. The four individuals were reportedly acting in support of ISKP. In July 2023, Germany and the Netherlands coordinated arrests targeting an ISKP-linked network suspected of plotting attacks in Germany. German police halted a plan to attack US and NATO military bases in Germany in April 2020. The four Tajik nationals were reported to be in contact with Islamic State officials in Afghanistan and Syria. The plotters used Telegram to access Islamic State bomb-making instructions and reportedly received audio and text messages from an IS operative in Syria. IS leadership also shut down a proposed plan by the men to travel to the Middle East to fight, encouraging them to wage war within “evil” Europe. After Moscow, ISKP’s propaganda refocused on Europe and specifically sporting events, including an image of a masked fighter standing in Munich stadium.

Notably, ISKP has been one of the most vocal and aggressive jihadist groups in exploiting hostile sentiments fueled by the Israel-Hamas war to threaten and incite violence against Jews and the West. In its English language magazine, the branch included a translated version of IS’s al-Naba editorial “Practical Steps to Fight the Jews,” and its own article provided a full page of instructions in an infographic titled “Practical Ways to Confront the Jews,” which called for killing Jews wherever they can be found.

Policy Recommendations

As mentioned above, Al-Azaim has published propaganda in more languages than any IS branch since the apex of the caliphate. The content is multilingual and explicitly calls for attacks worldwide, including against various Western countries and targets. In a sign of revealed preference, ISKP dedicates significant resources to its media jihad capabilities. In a way similar to IS core at its most dangerous, ISKP encourages its supporters to create propaganda independently, amplifying its messaging and accelerating the radicalisation process for some individuals. Moreover, ISKP is active on myriad tech platforms where it communicates, spreads, and stores its propaganda.

Unlike in the heyday of IS, there seems to be a lack of urgency in the counterterrorism community to deal with the challenge posed by Al-Azaim. Only a comprehensive and full-throated response can succeed in limiting the reach of ISKP’s propaganda. Governments and policymakers would be wise to partner with social media and tech companies to harness the ability of artificial intelligence to engage in automated content moderation and takedown. Deplatforming is not a silver bullet, but it needs to be part of a broader approach. When deployed as another pillar of a coordinated and sustained campaign, which also has an intelligence and policing component, takedowns can be effective and significantly disrupt jihadists’ online activities.

The public-private partnership between governments and social media/tech companies needs to be more than simply a buzzword. These partnerships require sustained funding and enforcement mechanisms, as tech companies are more agile than governments in responding to dynamic online content and the adaptability of terrorist groups operating online. Engaging and incentivising technology companies in developing strategies to detect, report, and remove ISKP digital material is vital to keeping pace with the adaptability of its creators. While a large amount of jihadist propaganda is shared on the largest platforms — Facebook, X, Instagram, TikTok — these companies have systems and staff in place that do attempt to clamp down on the material.

ISKP’s official and supportive media remains resilient by using a scattering of platforms and storage sites to keep its propaganda online, including unmoderated archives and so-called “alt-tech” social media platforms that do not make significant attempts at moderation. Engaging with these private entities is particularly difficult as many view eschewing moderation or censorship as foundational to the business. For any effort to be truly impactful, a dual approach of legal pressure and public-private engagement needs to be applied in significant measure to encourage innovative and timely responses from platforms typically resistant to screen its content.

Like de-platforming, even extremely diligent content moderation is not a panacea for dealing with highly adaptable terrorist propaganda. When some of the measures mentioned in this section are used in tandem, they can limit or isolate the outlets that are still willing to host the material. Reducing the reach of ISKP’s media jihad even further is essential to curtailing its influence and ability to inspire individuals abroad to action.