South Asia Intelligence Review

Democracy, Disorder, and the Battle for Renewal

On January 15, 2026, Senior leader Gagan Kumar Thapa was elected President of the Nepali Congress (NC) unopposed during the party’s second Special General Convention (SGC) held at Bhrikutimandap in Kathmandu. The SGC was convened with the backing of over 60 per cent of general convention delegates. Election Committee Coordinator Sitaram KC announced the results at 12:30 am. Along with Thapa, the SGC unanimously elected other office-bearers, including Vice Presidents Bishwa Prakash Sharma and Pushpa Bhusal, and General Secretaries Guru Raj Ghimire and Pradip Paudel. Several Joint General Secretaries were elected under cluster-based representation. The convention followed a political deadlock after talks with then NC President Sher Bahadur Deuba failed. Earlier, the NC Central Committee (CC) had suspended Thapa, Sharma and Joint General Secretary Farmullah Mansur. Despite disciplinary action, the Special General Convention proceeded to elect a new party leadership.

On January 16, 2026, the Election Commission formally recognised Gagan Kumar Thapa as the President of NC and updated its records with the details of the office bearers elected from the SGC, concluding that the event was conducted in accordance with the law and the party statute. Acting Chief Election Commissioner Ram Prasad Bhandari said the commission relied on three key grounds to decide on updating the party’s details:

The NC statute allows 40 per cent of general convention delegates to demand a special general convention, and the commission found that such a convention had been held as mandated.

The statute clearly establishes general convention delegates as the supreme authority of the party, making their decisions binding.

The commission noted that there was no recorded dissent over the demand for a special general convention, confirming that it was convened in line with the statute.

With the Commission’s decision, all resolutions passed by the SGC held from January 11 to 14 gained legal recognition. The Election Commission’s subsequent recognition of Thapa’s faction as the official NC transformed an internal dispute into an institutional schism, reviving memories of the party’s traumatic splits in 1953 and 2002.

The Election Commission’s recognition of Gagan Kumar Thapa’s leadership did not end the crisis within the Nepali Congress. Instead, it formalised a party split, with the ousted leadership coalescing into a rival faction under Sher Bahadur Deuba. Deuba and his supporters rejected the legitimacy of the SGC, describing it as “unconstitutional, coercive, and in violation of the party statute.” While the Deuba group previously functioned as the “Establishment” faction, they are now challenging their status as a “dissident” or “breakaway” faction, following the EC decision. Deuba has publicly maintained that he remains the “legitimate president elected by the 14th General Convention” and has accused the Thapa camp of “engineering a party takeover under the cover of street pressure and institutional manipulation.” The principal figures aligned with Deuba include senior leaders Purna Bahadur Khadka, Dr. Shekhar Koirala, Bimalendra Nidhi, Arjun Narsingh KC, and several former ministers and provincial-level party chiefs. The faction retains influence within parts of the party’s traditional organisational base, particularly among older cadres, rural committees, and leaders embedded in patronage networks.

Since mid-January 2026, the Deuba faction has pursued a dual strategy: initiating legal challenges against the Election Commission’s decision, while mobilising supporters through parallel party meetings, protest statements, and threats of street agitation. This has effectively created a situation of dual authority, with two competing centres of power claiming continuity of the NC legacy. Rather than resolving the leadership dispute, the institutional recognition of Thapa’s faction has, therefore, deepened the schism, transforming an internal party conflict into a structural fracture with implications for electoral coherence, opposition politics, and overall political stability in the run-up to the March 2026 elections.

It is useful to recall here that around 1952–1953, shortly after the party’s early years post-democracy, due to leadership dispute mainly between Bishweshwar Prasad Koirala (BP Koirala) and Matrika Prasad Koirala over government formation and direction, led to factional tensions and a split within the party. This was considered as the first significant break in NC’s history during the early democratic period. Later, in 2002, in a deep dispute during the Maoist insurgency era, the then-Prime Minister Sher Bahadur Deuba dissolved the House of Representatives (HoR), extended the state of emergency without full party consensus, and was expelled by the party’s disciplinary committee. This culminated in Deuba’s faction registering separately as NC (Democratic) on September 22, 2002. Nevertheless, on September 25, 2007, the NC (Democratic) later merged back into NC reuniting the split groups.

Coming back to the present day, the split within the NC marks a defining moment in the country’s post–Gen Z upheaval political trajectory. What unfolded in January 2026 was not simply another episode of factional infighting but a convergence of generational revolt, institutional decay, and contested geopolitical narratives that together threaten to hollow out the NC’s historic role as a stabilizing force in Nepal’s fragile republic. The split in NC was the result of:

Long-term factional rivalry

Leadership authoritarianism

Disagreements over crisis management

Failure of internal democratic norms

Indeed, this conflict is rooted in long-standing structural contradictions. Years of unstable coalitions, blurred ideology, and governance failures eroded public trust, particularly among younger voters. The Gen Z uprising of September 2025, which toppled the KP Oli government amid mass protests against corruption and censorship, accelerated this crisis. NC, divided and reactive during the unrest, emerged weakened and internally polarized. For reformists, the uprising underscored the urgency of renewal; for the old guard, it represented a destabilizing force to be managed rather than embraced.

Gagan Thapa became the symbolic center of this reformist moment. His appeal lies in a discourse of accountability, service delivery, and institutional reform that resonates with urban, educated constituencies. Critics, however, portray his rise as externally engineered, pointing to past WikiLeaks cables describing him as a U.S. Embassy contact and to Western-funded democracy and youth programs operating in Nepal. From this perspective, Thapa’s alignment with Gen Z rhetoric and reformist tropes is seen as part of a broader Western strategy to counter Chinese and Indian influence. Such claims, however, remain strongly contested. Engagement with foreign diplomats is routine across Nepal’s political spectrum, and there is no clear evidence of organizational control linking Thapa to decentralized Gen Z activism. The youth movement itself is deeply skeptical of party politics and resistant to co-optation. Thapa may benefit from the prevailing anti-elite mood, but he does not command it, and any perception of opportunism could quickly undermine his credibility.

The road ahead is perilous. A Thapa-led NC seeks to capitalize on youth discontent and organizational legitimacy ahead of elections, while Deuba’s camp fights back through street protests and legal challenges. Prolonged litigation or further fragmentation could paralyze the party, ceding space to rivals and deepening systemic instability. Ultimately, the NC split reflects a broader legitimacy crisis in Nepal’s political system. Without genuine internal democratization, improved institutional performance, and meaningful youth inclusion, this implosion may prove not an exception but a harbinger of wider political unraveling.

These developments compound the consequences of the nationwide Gen Z protest movement on September 8-9, 2025, the most violent episodes in Nepal’s recent political history, which exposed the rupture between Nepal’s political elite and its wider society. The Gen Z protests transformed latent public anger into an unprecedented mass uprising. While the immediate trigger was the government-imposed ban on multiple social media platforms on September 8, 2025, the movement rapidly evolved into a broader rebellion against corruption, political dynasties, economic stagnation, and entrenched impunity. What began as student-led demonstrations in Kathmandu quickly spread across major urban centres, overwhelming an unprepared and internally divided state apparatus.

Reportedly, on September 8, 2025, tens of thousands gathered in Kathmandu at Maitighar Mandala and New Baneshwor for a protest organized by the Non-Governmental Organization (NGO) Hami Nepal, led by civic activist Sudan Gurung. What began as a peaceful rally escalated when some protesters attempted to breach the federal parliament complex and clashed with security forces. Police responded with tear gas, water cannons, rubber bullets, and live ammunition. Video evidence later confirmed that many protesters, including students, were killed by gunfire, with at least 19 deaths reported that day. The Home Minister resigned, and a social media ban was lifted in the evening. But violence intensified nationwide on September 9, 2025. Prime Minister K. P. Sharma Oli resigned and fled to an Army barracks. Protesters torched major state institutions, political party offices, and leaders’ residences. Prisons were attacked across the country, allowing more than 13,000 inmates to escape. The Army took control as airports were shut and politicians evacuated. By September 10, 2025, army patrols restored partial order, while protesters discussed interim leadership online. Former Chief Justice Sushila Karki emerged as a consensus figure. Talks followed on September 11, 2025, as the death toll rose to at least 34. On September 12, 2025, Sushila Karki was sworn in as Interim Prime Minister. Parliament was dissolved, elections were set for March 5, 2026, and calm gradually returned. In the eventual total, at least 76 people were killed and over 2,100 injured. Curfews were lifted on September 13, 2025, and relative calm returned to Kathmandu. The interim government pledged compensation, investigations, and national recovery.

While Karki’s judicial background and reputation for integrity initially inspired cautious optimism, her government inherited a deeply polarised society, weakened institutions, and a pervasive legitimacy deficit. A key mandate of the Interim Government was the conduct of parliamentary elections scheduled for March 5, 2026. These elections have acquired the character of a referendum on Nepal’s democratic resilience. Preparations are underway amid formidable challenges: damaged public trust, low institutional morale, economic distress, and the possibility of renewed mobilisation by youth groups and other disaffected constituencies. Reforms such as the lowering of the voting age to 16, limited overseas voting pilots, and outreach to youth organisations signal intent, but their impact remains uncertain given the compressed timeline and fragile security environment.

In another development, on January 15, 2026, Netra Bikram Chand, chair of the Chand-led Communist Party of Nepal-Maoist (CPN-Maoist-Chand), and Miraj Dhungana, leader of the Gen-Z group, reached an agreement to cooperate in a joint political movement. The two sides signed a four-point agreement in Kathmandu, to work together to advance protests and political actions in the coming days. According to the agreement, both sides will struggle to address the demands raised by the Gen-Z movement, push for constitutional amendments in line with public aspirations, work toward the formation of a stable government, establish a special judicial body to combat corruption, and pursue the progressive restructuring of the state.

2025 had also witnessed the March 28, 2025, violence that marked a qualitative shift in Nepal’s internal security landscape. Thousands of supporters of former King Gyanendra Shah, mobilised by the Joint People’s Movement Committee for the Restoration of Monarchy, clashed with the Police during a rally in the Tinkune area of Kathmandu. What was projected as a peaceful demonstration quickly escalated into coordinated violence, including arson attacks on government vehicles, vandalism of hospitals and media houses, and looting of commercial establishments. At least two civilians were killed, and 110 persons – 53 Nepal Police personnel, 22 officers from the Armed Police Force (APF) and 35 protesters – sustained injuries, as violent clashes between the security personnel and pro-monarchy protesters erupted during the royalist demonstration at Tinkune.

The targeting of prominent media institutions such as the Annapurna Media Network and Kantipur Publications was particularly alarming, reflecting a growing intolerance toward dissenting voices. The alleged role of businessman Durga Prasai as a ‘field commander’, and the arrest of senior Rastriya Prajatantra Party (RPP) leaders on charges of inciting violence, further highlighted the political undercurrents behind the unrest.

Despite the turbulence, Nepal remained free of insurgent activity through 2025. No terrorism-linked fatalities were recorded during the year, continuing a trend observed since 2021. The Comprehensive Peace Agreement of 2006, the dismantling of Terai-based armed groups by 2012, and the 2021 agreement with the Netra Bikram Chand-led Communist Party of Nepal-Maoist (CPN-Maoist-Chand) have effectively closed the chapter of armed rebellion. Nepal also recorded zero terrorism-related fatalities in 2024, though it would be an error to mistake stability for the absence of risk.

On January 16, 2026, injured participants of the Gen-Z movement and families of those killed during the protests staged a sit-in at the Prime Minister’s Office, saying their demands remain unmet. They said repeated assurances from authorities had not translated into concrete action. Of the demands raised by the protesters, the following remain pending or only partially addressed:

Accountability for Police violence – No independent judicial commission with prosecutorial powers has been constituted; no senior officials have been held responsible for the deaths and injuries.

Prosecution or removal of responsible officials – Home Ministry and security leadership figures implicated in ordering or permitting live fire remain in office.

Time-bound anti-corruption action – No concrete investigations or prosecutions against senior political figures linked to corruption or the “nepo kid” allegations.

Legal safeguards against future digital shutdowns – No law or binding policy has been enacted to prevent arbitrary social media bans.

Institutional reforms to protect civil liberties – Reforms related to freedom of expression, digital rights, and protest policing remain unimplemented.

Youth-centric economic measures – No credible policy package addressing youth unemployment, political patronage, or governance reform has been announced.

Comprehensive compensation framework – Compensation and long-term medical support for victims and families remain incomplete or undefined..

Further, the social media ban was lifted, but without legal guarantees, making this demand only partially fulfilled. In short, structural accountability, legal reform, and anti-corruption measures are the core unresolved demands that prompted the sit-in at the Prime Minister’s Office.

Another area of concern was the continued activity of radical Islamist organisations, particularly Islami Sangh Nepal (ISN). While no acts of terrorism were attributed to these groups, their expanding organisational footprint, foreign ideological and funding links, and frequent mass religious gatherings raised red flags for security agencies.

Nepal’s placement on the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) grey list in February 2025 also marked a significant deterioration compared to 2024. The decision reflected Kathmandu’s failure to fully implement reforms to combat money laundering and terrorist financing. Although the government introduced a Bill to regulate the funding of NGOs and INGOs, particularly those receiving foreign assistance, tangible outcomes remained uncertain at the end of 2025. The persistence of unchecked foreign funding, including support linked to Pakistan-based entities, poses long-term risks. Compared to 2024, when such concerns were present but less pronounced, 2025 saw increased international scrutiny and reputational damage for Nepal.

The challenge for Nepal is to deepen democracy, restore political morality, and rebuild public trust in institutions. Without meaningful reforms, the cycle of instability – the country has seen 15 Prime Ministers since 2008 – may intensify, increasing the risk that street mobilisation and populist violence could one day threaten the hard-won peace. In contrast to 2024, when political instability unfolded largely through parliamentary manoeuvring, 2025 witnessed the direct intervention of the street in shaping political outcomes.

The Gen Z movement fundamentally altered Nepal’s political calculus, demonstrating that governance without legitimacy is no longer sustainable. Whether the March 2026 elections can channel this disruptive energy into democratic renewal, or merely reset the cycle of instability, will be the most critical test facing the country in the immediate future. Democracy remains Nepal’s best option, but only a more accountable, inclusive, and principled democratic order can prevent the country’s chronic volatility from spiralling out of control.

Nagaland: Weakening Insurgency

Nagaland continued to experience a markedly subdued insurgency landscape through 2025, a trend that has extended into the opening weeks of 2026, with militant activity remaining sporadic, fragmented, and largely non-kinetic. The only insurgency-related incident recorded in the State in 2026, so far, occurred on January 15, when an active cadre of the United Liberation Front of Asom–Independent (ULFA-I), Amarjit Moran aka Dhananjay, surrendered before Security Forces (SFs) in Mon District. The surrender was symbolically consequential, underscoring the sustained erosion of ULFA-I’s organisational resilience and the diminishing viability of Nagaland’s eastern districts as secure fallback zones for Assam-based insurgent groups.

This development followed a limited but telling series of surrenders recorded in 2025, when at least seven ULFA-I cadres surrendered in four separate incidents across Nagaland, reinforcing a gradual trend of militant attrition.

On September 14, 2025, two ULFA-I cadres, Anupam Asom and Chinmoy Asom, surrendered before the Nagaland Police at an unspecified location in Nagaland.

On August 7, 2025, one ULFA-I cadre, Chunoo Gogoi aka Kalyan Asom (28), surrendered before the Assam Rifles in Nagaland, along the Indo-Myanmar border.

On August 6, 2025, an active ULFA-I cadre, Jit Asom aka Janardan Gogoi, surrendered before authorities in Nagaland. Following his surrender, the former insurgent was taken into Police custody by the Charaideo District Police in Assam for further questioning and legal formalities.

On August 6, 2025 three cadres of ULFA-I, Dwipjyoti Saikia, Antony Moran and Paragjyoti Chetia, surrendered at an Army camp in the Mon District of Nagaland, near the India-Myanmar border.

Collectively, these incidents demonstrated the cumulative impact of sustained counter-insurgency pressure, tightened border surveillance, and declining morale within ULFA-I’s rank and file.

Partial data compiled by the South Asia Terrorism Portal (SATP) indicates that Nagaland recorded one militant surrender in 2026, seven in 2025 (all ULFA-I cadres), and five [one Naga National Council-Non Accordist (NNC-NA) and four Nationalist Socialist Council of Nagaland-Khaplang (NSCN-K)] in 2024. Since SATP began systematically documenting insurgency trends in the Northeast in 2000, the State has registered a total of 249 militant surrenders across 35 separate incidents. This long-term pattern reflects not only the effectiveness of security operations but also the prolonged stagnation of insurgent political objectives, factionalism, and the gradual normalisation of ceasefire and dialogue mechanisms.

Arrest trends during the same period further corroborated the contraction of insurgent activity. As of mid-January 2026, Nagaland has not recorded any militant arrests, reflecting the near absence of active operational networks on the ground. During 2025, the State recorded the arrest of 11 militants in six separate incidents. These included two cadres of the National Socialist Council of Nagaland–Reformation (NSCN-R), one cadre of the National Socialist Council of Nagaland (NSCN), two cadres of ULFA-I, five cadres of NSCN-K, and one militant whose organisational affiliation could not be ascertained. In 2024, arrests were comparatively higher, with 20 militants apprehended in 12 incidents, including 13 cadres of NSCN-K, three cadres of the National Socialist Council of Nagaland–Isak-Muivah (NSCN-IM), and one cadre each belonging to ULFA-I, NSCN-K–Yung Aung (NSCN-K-YA) and National Socialist Council of Nagaland–Khaplang–Niki Sumi (NSCN-K-NS), along with one unidentified militant. Since 2000, Nagaland has recorded the arrest of 2,372 militants across 1,255 incidents, underscoring the scale of enforcement actions undertaken over the course of the insurgency and the gradual tapering of such interventions in recent years.

Most notably, Nagaland recorded zero insurgency-related fatalities in 2025, marking one of the calmest years since the onset of armed militancy in the State. This continued a downward trend observed over recent years. In 2024, the State recorded three fatalities – two militants and one civilian – in three separate incidents, while in 2023, three militants were killed in two incidents. Since 2000, insurgency-related violence in Nagaland has claimed 833 lives, including 605 militants, 192 civilians, 22 SF personnel, and 14 in the Not-Specified (NS) category, across 455 incidents. The complete absence of fatalities in 2025 is a striking indicator of the dramatic contraction of armed confrontation, though it does not signify the total disappearance of insurgent influence.

Despite the lack of lethal violence, coercive practices by armed groups persist in subtler, but nonetheless consequential forms. On December 30, 2025, two dumper drivers and an excavator operator engaged in a road construction project in Meluri District were attacked at gunpoint by an NSCN-R cadre, identified as a tatar (local functionary) named Müsumi. The incident occurred between Phokhungri town and Avakhung village, where a two-lane road project under Package-III was being executed by Bharat Construction Company Limited. One of the drivers sustained serious injuries. Although the immediate trigger was reportedly a dispute over giving way to a vehicle, the incident vividly illustrates the enduring capacity of armed cadres to resort to intimidation and violence with relative impunity, particularly in remote and poorly governed areas.

Similarly, on October 24, 2025, Nagaland Police rescued an abducted businessman from Dubagaon under Dimapur Police Station and arrested two NSCN-R cadres, Antu Mech (30) and Nagato Sumi (37), along with three accomplices. This incident reaffirmed that abduction and extortion remain integral to the operational economy of splinter groups, even as large-scale insurgent violence has receded. Such criminalised activities underscore a critical transformation in Nagaland’s insurgency, wherein armed groups increasingly function as coercive networks embedded within local socio-economic structures, rather than as ideologically driven revolutionary movements.

Inter-group dynamics further shaped the security environment during 2025. On July 3, 2025, the NSCN-Khaplang faction and the Konyak Union issued a stern warning to ULFA-I, demanding an immediate halt to all activities within Konyak jurisdiction, particularly in the Mon District. The statement accused ULFA-I operatives of continuing to use the area as a safe haven while engaging in abduction and extortion in Assam, despite earlier warnings issued in April 2021. This development was significant, reflecting growing local resistance to the presence of non-Naga insurgent groups and highlighting the increasingly assertive role of tribal bodies in regulating armed activity within their territories.

The political dimension of the Naga issue remained intensely active and deeply contested throughout 2025. On June 11, 2025, the Centre’s interlocutor, A.K. Mishra, held crucial meetings with NSCN-IM ‘general secretary’ Thuingaleng Muivah and representatives of the Working Committee (WC) of the Naga National Political Groups (NNPG) at Camp Hebron in Peren District. The discussions focused on evolving a comprehensive execution framework that could potentially reconcile the 2015 Framework Agreement with the 2017 Agreed Position. Leaders from both sides publicly acknowledged past disunity and expressed cautious optimism, yet core disagreements – particularly NSCN-IM’s insistence on a separate Naga flag and constitution – continued to stall any conclusive settlement.

Frustration over the prolonged negotiations was repeatedly articulated by NSCN-IM leaders. On March 21, 2025, NSCN-IM ‘chairman’ Q. Tuccu accused the Government of India of deliberately delaying a political solution and employing divisive tactics to weaken the organisation’s negotiating position. He alleged that the creation of NNPGs was intended to dilute the Framework Agreement and criticised sections of Naga civil society for aligning with what he described as India-backed factions. Earlier, on January 19, 2025, NSCN-IM accused the Government of India of deceitful handling of the Indo-Naga dialogue, reiterating its sovereign claims and condemning the continued incarceration of its kilonser Alemla Jamir.

Internal fragmentation within Naga political formations remained a persistent impediment. On December 15, 2025, retired ‘general’ Niki Sumi, president of the NSCN-K–Niki Sumi faction (NSCN-K-NS), publicly criticised the splintering of Naga groups, warning that tribal blocs and parallel negotiations were eroding prospects for a unified settlement. His remarks reflected a growing recognition within insurgent and ceasefire signatory circles that disunity has become a structural weakness undermining the Naga movement.

The Government of India maintained a calibrated security posture throughout the year. On September 26, 2025, the Union Ministry of Home Affairs extended the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act for six months in nine districts and 21 police station areas across five additional districts, despite improved security indicators. The extension underscored lingering concerns regarding residual militant influence and the strategic sensitivity of Nagaland’s border districts. Earlier, on September 22, 2025, the Centre extended the ban on NSCN-K and its factions for another five years under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA), citing threats to sovereignty, extortion, and links with other banned outfits.

The political discourse in late 2025 was further complicated by the demand for a Frontier Nagaland Territory. On December 21, 2025, a high-level tripartite meeting between the Government of India, the Government of Nagaland, and the Eastern Nagaland People’s Organisation (ENPO) signalled a serious attempt to address long-standing grievances in the eastern districts. While the talks reduced immediate tensions, they added another layer of complexity to an already intricate political and security landscape.

Overall, 2025 marked a year of conspicuous calm in Nagaland’s insurgency profile, characterised by zero fatalities, limited surrenders, and the near absence of direct armed confrontation. However, this calm rests on a fragile equilibrium sustained by ceasefires, political fatigue, and tactical restraint rather than by a conclusive resolution of core issues. The persistence of coercive criminal activity, factional fragmentation, and unresolved political demands suggests that, while large-scale violence has receded, the structural drivers of instability endure. While security indicators point toward consolidation, the durability of peace will remain contingent on achieving a credible, inclusive, and unified political settlement acceptable to all stakeholders.

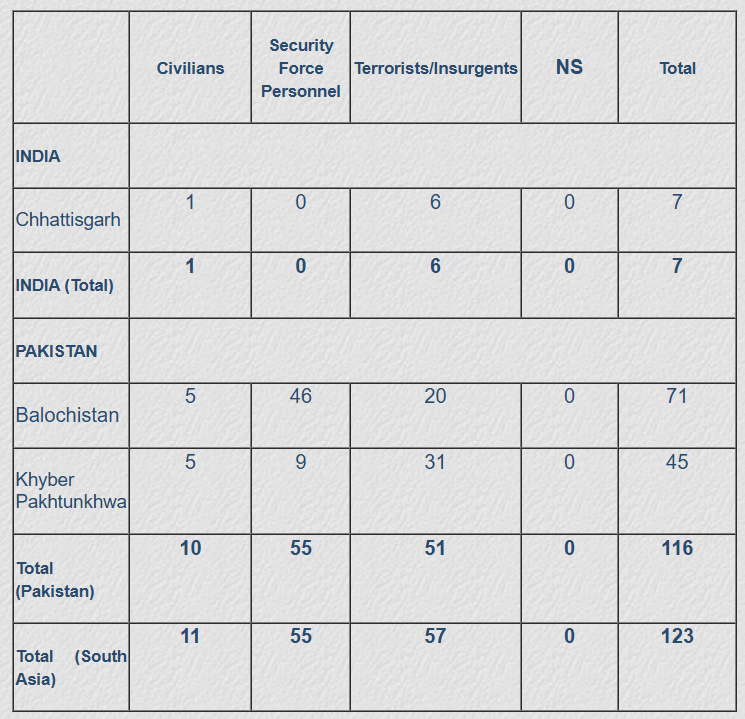

Provisional data compiled from English language media sources.