Battle Of Legacies In China As Xi Consolidates Position – Analysis

China has one of the most hide-bound rituals for its political events that overawe its audience with pageantry, but with a definite intention of such proceedings. The November plenary session, in which the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) elite gathered, in the run-up to the 2022 National Congress was no different.

The Plenum communique touts that Xi Jinping Thought will be the main driver of turning the nation into a “great modern socialist country” by 2049, which mark the centenary of CCP’s takeover. It credits him for increasing China’s strength, and solving problems that his predecessors were unable to tackle, and consequently produced a better life for the people. This year, the CCP declared that nearly 850 million people had been brought out of poverty since it established the People’s Republic in 1949, and that extreme poverty had been eliminated. Since 2012, coinciding with Xi becoming CCP’s boss, about 100 million are said to have been lifted out of poverty.

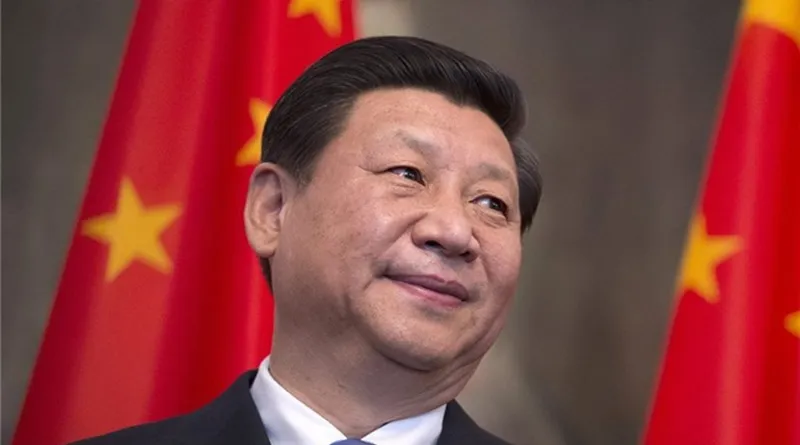

Thus, the messaging from the key CCP conclave is clear: Xi seems to have further consolidated his push for a third term after being featured in a ‘historical resolution’ adopted to celebrate the ruling party’s centennial. This is the third such resolution since the CCP’s founding in 1921 and many reckon that it uplifts Xi to the same level as Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping. Furthermore, this session has laid the groundwork for the Party Congress where Xi is expected to get an unprecedented third term in the top job.

The objective is to confirm Xi’s legitimacy and authority, and make a credible argument for people to buy into the party’s historic mission. Things appear smooth with Xi having nearly decimated any resistance to his rule and cemented his grip on the CCP. This is reflected in the Plenum declaring that Xi has resolved the problem of weak oversight over the Party. Unlike the run-up to the Party Congress in 2012, when a provincial boss of Chongqing, Bo Xilai, had been rumoured to have thrown the spanner in the works. Amidst the power struggle in the CCP, the question of how to address the issue of the yawning wealth gap was also creating schisms within the elite personified by the ‘cake doctrine’ [dàngāo lùn (蛋糕论)]. One section had cast its lot behind apportioning the cake, which represented the economic gains, more equitably, whereas another sought to put off redistribution of the spoils for another day. Bo’s policies aimed to reduce the wealth gap and ease the rural-urban divide, including through the construction of public apartments for students, migrants, and low-income groups.[i] In 2007, he started a pilot project to make it easier for rural residents to obtain urban status under the hukou (household registration) system that determines educational opportunities, tax liability, and property rights. Speculation persists till this day that Bo had been showcasing his egalitarian ‘Chongqing model’ to make a grab for the top job in Beijing—elbowing then Vice President and heir apparent Xi Jinping.[ii]

Learning from this incident, Xi’s instinct has been to consolidate his position. Bo and other key figures in the army and security establishment were jailed on charges of corruption and abuse of power. A top Chinese official later disclosed that some high-ranking members of the CCP had schemed to seize power from Xi Jinping; an admission that laid bare a power struggle in the CCP denting the Party’s efforts to project a unified face. When you can’t beat them, take a leaf out of their book, seems to be Xi’s credo. The Chongqing model has now metamorphosed on the national scene in form of the pursuit of ‘common prosperity’. In what may seem as a self-goal, China’s regulators are gunning for some of the country’s biggest tech firms, erasing trillions in stock value, and sparking alarm amongst the nation’s entrepreneurs. The government’s actions have pushed the nation’s largest realty firm on the brink of a collapse, sending a shudder through international markets.

It is not just entrepreneurs who are feeling the heat, but even the average Joe as Xi’s seeks to remould society itself. In a crackdown again celebrities, the entertainment industry has been directed to ensure all underage artists finish the mandatory nine years of schooling.

Drawing parallels

During his lifetime, Mao was venerated as the “Great Helmsman” despite disastrous policies like the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution in which millions perished. Such was the aura around him that it was only after his demise that the CCP began to take an objective view. The ‘historic resolution’ adopted by top party leadership, which was made public on 16 November, reasserts Mao foibles like the purge of intellectuals in the 1950s, the collectivisation of the nation’s agricultural and industrial economy in the late 1950s, and the Great Leap Forward. Mao is held responsible for the Cultural Revolution, which the resolution terms as a catastrophe resulting in a decade of chaos.

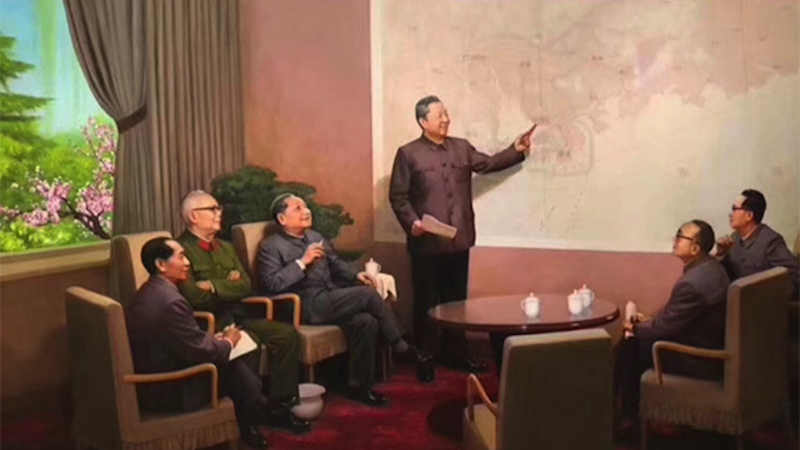

There are many parallels between Mao and Xi, prominently a personality cult and an eponymous philosophy, which has become mandatory reading and pervades every sphere. This means that it may be tough to have a realistic assessment of Xi’s programmes in his lifetime or do a course correction where needed as a personality cult precludes such an analysis. Here, Xi faces a tall order. Deng decentralised China’s governance model allowing provincial leaders to take centre stage and experiment with reform. In the early 1980s, the coastal Guangdong province got a green light to formulate its own foreign trade policy decisions and to invite foreign investment into demarcated areas along the border with Hong Kong. Deng’s pointsman to oversee the project of special economic zones in Shenzhen was Xi Zhongxun, Xi’s father. Deng also extricated the party-state from the economy, which allowed the private sector to flourish and set China on a path to becoming the world’s second largest economy. On the contrary, Xi has augmented the role of the state sector of the economy and embedded the CCP into the private sector. Authoritarian systems believe in the truism that those who control the past, control the future. From his dominant position, Xi has the wherewithal to rewrite history. Hence, on the 40th anniversary of China’s economic liberalisation in 2018, Xi aggrandised his father’s contribution in the Shenzhen pilot, which paved the way for China’s industrialisation, vis-à-vis Deng’s. An exhibition at the National Art Museum of China on the reform and opening up phase magnified Xi Sr at the expense of Deng (See image).

A November 2021 report by McKinsey Global Institute revealed that global wealth has tripled over the last two decades, rising to US $514 trillion in 2020, from US $156 trillion in 2000. In 2000, the People’s Republic’s wealth totalled US $7 trillion that soared to US $120 trillion in 2020. China joined the World Trade Organisation in 2001, and this has paved the way for it to accumulate wealth and convert it into power. The flip side of such a strategy has been that more than 65 percent of the wealth is concentrated in the hands of the 10 percent of the richest households.

The ‘historical resolution’ asserts that Deng’s liberalising the economy has led to harmful practices of “living lavishly” and “money worship”. This messaging obliquely points to Deng for contributing to the wealth gap in China, and applauds Xi for coming to grips with the challenge of income disparity. He must bear in mind that China’s economic reforms bore fruit from the late 1970s onwards after the state retreated from society and promoted free trade and private enterprise.

The resolution added that common prosperity will be the ultimate goal and that growth in GDP would not be the only benchmark of success. The crackdown on enterprise and CCP’s growing footprint in society following the drumbeat of common prosperity is a straw in the wind and gives us a peek into how Xi’s third term may look like. In addition to realty tax, levies on capital gains, and consumption of luxuries are likely to be on cards to redistribute the ‘cake’ amongst a wider population. Xi also aims to offer tax incentives to encourage charitable donations, like those pledged by Big Tech founders. However, investors are dialling down on China. Singapore state investment company, Temasek, exited from Chinese education and technology stocks, while diluting its stake in Alibaba and transportation major Didi Global.

Intermittent COVID-19 outbreaks in China have forced lockdowns. Under China’s National Health Commission “dynamic zero-COVID” the CCP shuts down areas where there are infections and to trace patients’ close contacts. This approach is much stringent than other nations despite China having achieved one of the world’s most expansive coverage rates for vaccination that covered nearly three-fourth of the population by mid-November. Frequent closures have resulted in loss of livelihood and incomes, culminating in bitterness. While Xi scrounges from the socialist playbook to quell public resentment, he must realise that history will judge him on his ability to strike a balance between wealth creation and how he distributes the cake.