How Iran’s quest for retaliation against Israel threatens Chinese interests

While China expresses public support for Iran’s right to “defend its sovereignty,” Beijing’s assertive rhetoric belies deep-seated anxiety surrounding the possibility of a wider regional conflict erupting.

Not long after Iran vowed revenge against Israel following the assassination of Ismail Haniyeh in Tehran last month, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi took to the phone and told his Iranian counterpart, Ali Bagheri Kani, “China supports Iran in defending its sovereignty, security and national dignity.”

While Wang and Ali were chatting, America dispatched a guided missile submarine, an additional aircraft carrier strike group and more state-of-the-art F-35 and F-22 fighter jets to reinforce its already formidable regional armada in an effort to deter Tehran and its proxies from exacting retribution. Saudi Arabia, the UAE and other regional players have likely since noted what it means to be part of the US security umbrella.

Needless to say, China has neither the inclination nor the capabilities to provide its so-called comprehensive strategic partner in Tehran with any such luxuries.

Iranian officials eventually said that a cease-fire in Gaza stemming from US-led talks last week might prevent it from exacting revenge — a rather convenient, face-saving way out. Perhaps coincidentally, the maneuver aligns seamlessly with China’s messaging, vindicating Beijing’s long-held assertion that the Israel-Palestinian conflict is the “core issue of the Middle East.”

Yet, as US Secretary of State Antony Blinken wrapped up his Middle East tour last month, a cease-fire agreement remains elusive, and the specter of Iranian retribution looms.

While China expresses public support for Iran’s right to “defend its sovereignty,” Beijing’s assertive rhetoric belies deep-seated anxiety surrounding the possibility of a wider regional conflict erupting.

Professor Niu Xinchun, who directs the Institute of Middle East Studies at China Institute of Contemporary International Relations, said, “If the Middle East really plunges into full-scale turmoil, China, as the region’s largest trading partner and the largest buyer of Middle East oil, will turn out to be the biggest victim.”

China’s economic stakes

Indeed, China sources roughly 40% of its oil imports from just six Middle Eastern countries: Saudi Arabia, Iraq, UAE, Kuwait, Qatar and Oman. In defiance of US sanctions, China imports between 1.1 to 1.4 million barrels per day of Iranian crude oil, accounting for roughly 10% of China’s oil imports.

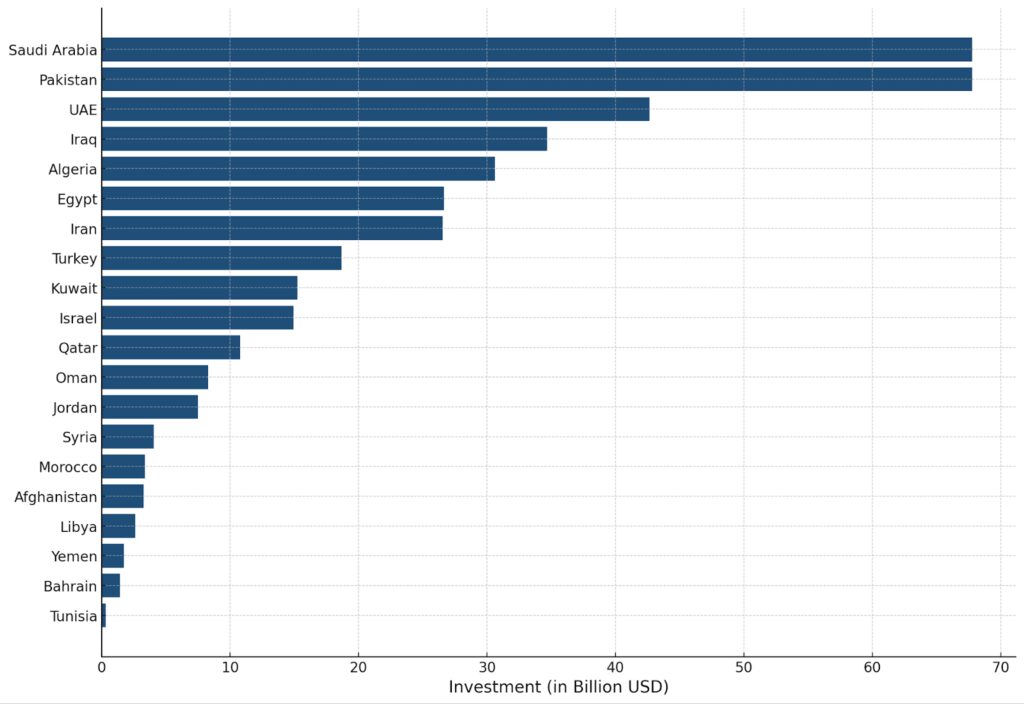

Meanwhile, China’s bilateral trade with the Middle East in 2022 reached a staggering $507.2 billion, according to China’s State Council Information Office. Data from the American Enterprise Institute’s China Global Investment Tracker reveals that PRC investments and contracts in the Middle East have exceeded $284.24 billion since 2005 — add North Africa and Pakistan to the equation, and the figure climbs to $388.9 billion.

Growing economic engagement led to an influx of Chinese citizens to the Middle East. As many as one million Chinese citizens are estimated to live in the region. Add to that the fact some 20% — 280 billion worth — of China’s total exports traverse the Suez Canal, and Beijing faces a strategic predicament of epic proportions due to the Houthi maritime disruptions.

Why not pull a lever?

A quick look at the data, and it’s not hard to see why some pundits have emphasized China’s influence. Jon Alterman, the director of the Middle East Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, told Foreign Policy in April that “China is the single country with the greatest ability to influence Iran, if it wants to be.” China represents roughly 30% of Iran’s trade portfolio but only 1% of China’s.

Despite repeated calls from US officials for China to exploit its asymmetric advantage over Tehran, Beijing has remained incredibly circumspect — and not without reason.

Though China has extended a lifeline to Iran in the face of US sanctions, their economic relations are far from rosy. Morteza Behrouzifar, an expert from Iran’s state-affiliated Institute of International Energy Studies, recently told local media that oil dealings with China have resulted in minimal financial returns for the Islamic Republic.

These illicit transactions are handled by independent Chinese refineries, called “teapots,” which collaborate with smaller financial institutions like the Bank of Kunlun. Because these transactions are conducted predominantly in Chinese renminbi, Iran can basically use it to purchase more Chinese products or let it sit in a Chinese bank, not much else. As Morteza put it, “We are selling oil under deplorable conditions — at low prices with steep discounts — and in return, we are importing substandard Chinese goods at best.”

The two countries announced a 25-year $400 billion deal in 2021. However, the much-hyped agreement has thus far disappointed; memorandums of understanding have masqueraded as binding agreements, and projects have failed to materialize. Morteza said, “This has led to the depletion of natural resources, including the National Development Fund (NDF), without any significant return on investment.”

Meanwhile, China’s trade with Iran’s rival, Saudi Arabia, surpassed $107 billion in 2023 — seven times more than the $14.6 billion China traded with Iran that year. China may offer Iran rhetorical support, sanctions relief and cover at the UN, but the bulk of China’s economic attention is focused squarely on the Gulf. The political implications of these commercial realities came into sharp focus in June of this year when China reiterated its support for the United Arab Emirates regarding its dispute with Iran over several islands in the Gulf, much to Tehran’s chagrin.

Undesirable consequences

Even if Beijing was willing to engage in more punitive economic statecraft, there is no guarantee that Iran would bend to China’s will. Moreover, Chinese strategists are likely wary that doing so could result in undesirable consequences.

Iran’s historical experiences of colonialism and imperialism have instilled in its leadership a tendency to resist external pressure. Over the years, Iran has developed strategies to offset any economic and political pressure: leveraging its regional influence, advancing its nuclear program, ramping up its cyber operations and mobilizing its networks of proxies in Gaza, Yemen, Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan and Pakistan.

Unlike the United States, which maintained over 30,000 troops and two aircraft carrier strike groups in the Middle East before the war’s outbreak (despite its pivot to Asia), China’s nascent military presence — an escort fleet comprised of just three ships and an estimated 200 marines stationed in Djibouti — represents no credible threat to Middle Eastern states or their proxies.

In January, China reportedly attempted to nudge Iran into reining in Houthi attacks against civilian ships in the Red Sea. By mid-March, news broke that Houthis told China and Russia that their ships, specifically, would no longer be targeted. Two days later, Houthi rebels launched a missile attack on a Chinese-owned oil tanker MV Huang. China has not commented publicly on the incident.