SOUTH ASIA INTELLIGENCE REVIEW Volume 23 No. 47

The Taint of Ambiguity

The long nights of ‘vengeance’ are over. It is time to ask, what has been achieved? Frenetic campaigns of falsehoods have enabled both sides to claim that they have engineered a notable victory. The whole truth, partly protected by legitimate interests of state, partly by vested partisan political interests, will never be known. But much can be measured in falsehoods as well.

The first truth that emerges through the noise is that the clear victory the Indian leadership sought has been tainted with ambiguity. Another is the tragic reality that domestic politics invariably trumps national security on both sides of the border.

Operation Sindoor was not a strategic imperative, nor was it timed for maximal strategic impact. It was a response to an orchestrated, partisan political campaign to whip up public sentiments, and was timed to meet partisan political, and not maximal strategic, objectives. For all the talk of “a compulsion to prevent, deter, and to pre-empt” attacks in India by Pakistan-based terrorist groups, the Operation simply had no potential to secure these objectives, and it was timed to a political calendar – the imperatives of being seen to have done ‘something big’, rather than doing something effective to secure these declared goals – that saw the launch of the coordinated strikes after a fortnight of media and public frenzy, and a succession of threats from the highest offices of the land. The result was, the Operation was initiated at a time when the Pakistani forces were on the highest levels of alert, dramatically escalating the risks for the attacking force.

Nevertheless, at the tactical and operational levels, Operation Sindoor did secure most of its objectives. At the tactical level, the delivery of nine precision strikes on widely dispersed selected targets deep inside Pakistan occupied Jammu and Kashmir (PoJK) and Pakistani Punjab – including one at Bahawalpur, over a hundred kilometres from the International Border, that killed at least three prominent Jaish-e-Mohammad (JeM) terrorists, and another two of the Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT) at Muridke, both in Punjab, was a signal military achievement. India claimed at least 100 terrorists killed; Pakistan insisted that just 31 ‘civilians’ had been killed in the first strikes.

It is significant that those who are constantly citing Chanakya as their inspiration, appear to have little familiarity with the concepts of deception and misdirection in war that he insisted on. Drumming up the ‘retaliation’ for a fortnight before the actual raids not only found the Pakistani Forces on the highest levels of alert, but also had the targets cleared of most of their regular occupants, particularly of the ‘highest value’ residents. Had the rhetoric of revenge been allowed to fade, and operations been held back till a measure of calm – and complacence on the other side – restored, the toll, particularly in terms of terrorist leadership, could have been substantially higher. But this would have required the national leadership to shoulder the responsibility of the intervening public criticism for their failure to act, and clearly such strength was lacking. And so, the Operation was fast forwarded, not with a view to securing maximal military objectives, but rather, to be harvested for political advantage.

At the operational level, the purpose of the strikes was to send a message to Pakistan that acts of terrorism, particularly of the magnitude reflected in the Baisaran massacre, would attract retribution, and that the lines in this regard had been pushed far forward from earlier retaliatory actions, such as the surgical strikes of 2016, and the Balakot bombings of 2019. In this, again, Operation Sindoor succeeded fully.

It is at the critical strategic level that Operation Sindoor fails, indeed, by design itself. If deterrence was the objective, Pakistan’s immediate reactions demonstrate its unwillingness to learn the lessons it was intended to be taught. Pakistan engaged in relentless tit-for-tat escalation in the wake of the first Indian strikes and, even after the declaration of a ceasefire, continued with shelling and drone attacks well into the night of May 10-11, demonstrating a recalcitrance that is likely to be reflected in its continued support to terrorism in Jammu and Kashmir (J&K).

It is useful to recall, here, that the United States (US) sustained a campaign of thousands of targeted drone strikes in Pakistan over nearly a decade and a half, but failed to prevent or deter Pakistani support to the Taliban and affiliated terrorist groups who were, at that time, killing US and Coalition forces, as well as Afghan Government forces. The sheer scale and persistence of these operations would have also had some pre-emptive impact, since many active armed groups were ‘neutralized’. But it is also useful to recall that one of the principal drivers of Taliban and terrorist recruitment for the ‘Afghan jihad’ was the US drone strikes. A limited action of the nature of Operation Sindoor is unlikely to have any lasting impact, though it may well become a rallying point for future recruitment to terrorist ranks. We have already heard statements by terrorist leaders in Pakistan promising vengeance. At least some will act on these threats. There is little evidence to suggest, moreover, that the Pakistani state and Army are simply going to give up on their ‘core issue’ and ‘jugular vein’.

Pakistan has fought four wars with India, and lost all these by general international consensus (and not just Indian claims), the 1971 war most graphically, losing more than half of its population and about 15 percent of its territory to the newly created Bangladesh. Not even these experiences have in any measure diverted it from its obsession with and misadventures in J&K and, by most measures, have deepened its commitment to ‘bleed India with a thousand cuts’.

More problematically, in its declaration that “Any terror incident will now be seen as an act of war,” New Delhi appears to be painting itself into a corner, with an inflexible commitment to direct retaliatory military action or war. Are we now to believe that a nation of 1.5 billion can be pushed to the brink of war by every terrorist attack? The world will have little tolerance for such unrelenting belligerence. There would be inevitable costs in terms of the country’s international standing, on the economy, investment, growth and development. Operation Sindoor has already resulted in an unacceptable US intervention in the conflict. Constant military confrontations and war-mongering will bring the ‘Kashmir issue’ more and more onto the international agenda – an objective Pakistan has long sought. Much like Union Ministry of Home Affairs vaunting declaration of ‘zero terrorism’, this poorly drafted declaration is likely to return to haunt the Centre.

Operation Sindoor will, of course, provoke some adaptive responses in the terrorist groups in Pakistan, and among their sponsors. Aware of the depths of the Indian strikes, as well as the possibility that future strikes may come without warning, the terrorist leadership and cadres are likely to be driven deeper underground, imposing at least some costs and operational difficulties on these groups. At the same time, these moves may create challenges for future retaliation as well, with a diminution in the number of visible and prominent terrorist targets for India to hone in on.

Much can also be learned from the bloodthirsty screaming, lying anchors and experts, knowingly spinning out falsehoods, or simply parroting a ‘line’ without any real information – the cream of the civilisational genius that is India today. We had Generals boasting that India had twice the Army, twice the tanks, nearly twice the Air strength, etc., as compared to Pakistan. But why should this be the case? India has 10.46 times Pakistan’s GDP and 5.6 times Pakistan’s population in 2024; as well as 9.5 times Pakistan’s territory. With a gigantic, growing and hostile power on its Eastern front as well, why has India’s leadership kept its Armed Forces’ strength at just twice that of its weaker neighbour? Why is it that, despite its ‘muscularity’ and purported commitment to national security, the present regime has kept allocations to defence at under 2 per cent of GDP (1.9 per cent under the current budget)?

Historically, India has sought nothing more than defensive parity with Pakistan, and has buried its head in the sand with regard to the burgeoning giant threatening the Eastern borders. This does not appear to have changed in any measure under the current dispensation, which remains far more sensitive to the monies being spent on the defence sector, and on the ‘burden’ of pensions for servicemen, than to the rising and menacing China, and the relentless mischief of Pakistan. Irrespective of our brave and boastful postures, if national expenditure on defence and security remains at present levels, India’s future cannot be secured.

Many who engaged in the vile, polarizing, bloodthirsty and ignorant propaganda of the weeks after the Baisaran massacre, have sought to justify their conduct in the name of ‘information warfare’. Certainly, the criticality of information warfare in modern conflict cannot be denied and this is the justification put forward by some of the most virulent propagandists. But the overwhelming burden of purported information warfare during this crisis was directed, not against the enemy, but at the domestic population [this was equally true of Pakistani propaganda], underlining the fact that the weight of state or state directed actions after Baisaran was overwhelmingly motivated by domestic partisan politics, and not by the nation’s strategic and security interests.

Operation Sindoor will have significant consequences, beyond any initial calculus, not only for Pakistan, but for India as well. Within hours of the announcement of the ceasefire, a savage political campaign was launched by the Opposition in India to portray Prime Minister Modi as weak, for having succumbed to Donald Trump’s bullying, even though Operation Sindoor had purportedly achieved nothing tangible. At the same time, sections of the international media began to push the idea that it was India that approached Trump to seek intercession to end the hostilities. These themes undermine the partisan and ultra-nationalist narrative that was imposed on the Baisaran massacre, on Operation Sindoor, and for years, on the conflict in J&K. It is likely that the majoritarian narrative will eventually be restored under the weight of sheer numbers of trolls and the distribution of resources. Nevertheless, at least some of the virulence of radical forces in the country has already been turned against those who have long provoked them. Like the revolution, polarizing ideologies of hate eventually devour their own children.

Resilience amid threats

In 2024, Sri Lanka’s security landscape remained relatively stable but complex, shaped by a mix of domestic challenges and volatile regional dynamics. While the threat of large-scale terrorism has significantly reduced since the end of the civil war in 2009, concerns persist around sporadic incidents of religious and ethnic tensions, particularly involving extremist elements across communities. No terrorism-linked fatality was recorded in Sri Lanka in 2024.

As of May 2025, Sri Lanka continued to maintain a stable security environment, with no terrorist attacks reported in recent years. According to a report released on March 5, 2025, the country has been recognized for its low terrorism impact, ranking 100th out of 163 countries, with a score of zero in the 2025 Global Terrorism Index, placing it among the safest nations globally in terms of terrorist threats.

On May 3, 2025, Sri Lankan authorities conducted a security sweep in Colombo’s Bandaranaike International Airport on a flight arriving from Chennai in India, after receiving a tip-off about a suspect linked to the Pahalgam terrorist attack in India. The aircraft was thoroughly searched, and no arrests were made. Nevertheless, the Sri Lankan government reiterated its commitment to national security, emphasizing that it will not allow any faction to use the country’s airspace or territory to attack another nation.

Six terrorists were arrested in five separate incidents in 2024, including:

November 30: A British Tamil citizen was arrested on arrival at Sri Lanka’s Bandaranaike International Airport, for suspected links with fundraising for the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE).

June 15: An accomplice linked with four suspected Islamic State (IS) operatives arrested in India, was arrested during an operation conducted by the Special Task Force (STF) near the Orugodawatta bridge at Wellampitiya in the Colombo District of the Western Province.

May 31: The Criminal Investigations Department (CID) and Terrorism Investigation Division (TID) of the Sri Lanka Police arrested a wanted suspect, Osman Pushparaja Gerard, in a joint operation conducted in Colombo City. Gerard was suspected to have coordinated the movement of four suspected IS operatives from Sri Lanka to India.

May 29: The Sri Lankan Police arrested two suspected IS operatives in the Bangadeniya area of Chilaw City in the Puttalam District of the North Western Province.

May 22: One terrorism suspect, with close connections to the four IS terror affiliates of Sri Lankan origin who were arrested at the Ahmedabad International Airport in India, was arrested by the TID in the Maligawatta Police Division of Colombo.

In October 2024, Arugam Bay, a popular tourist destination, faced a significant terrorist threat directed against Israeli tourists. Authorities linked the threat to the ongoing conflicts in Gaza and Lebanon, suggesting it originated from Iran as a form of “revenge” against Israel. Three suspects, all Sri Lankan nationals, were arrested on October 24, 2024, in this connection.

On June 3, 2024, in a gazette issued by Sri Lanka’s Secretary of Defence, the Government of Sri Lanka (GoSL) froze all funds, financial assets, and economic resources belonging to 15 groups and 210 individuals allegedly involved in terrorist and extremist activities. The designated groups include – the Tamil Rehabilitation Organization (TRO), Tamil Coordinating Committee (TCC), World Tamil Movement (WTM), Transnational Government of Tamil Eelam (TGTE), World Tamil Relief Fund (WTRF), Headquarters Group (HQ Group), National Thowheed Jama’ath (NTJ), Jama’athe Milla’athe Ibrahim, Willayath As Seylani, National Council of Canadian Tamils (NCCT), Tamil Youth Organization (TYO), Darul Adhar Ath’thabawiyya, Sri Lanka Islamic Student Movement (SLISM), and Save the Pearls.

Before that in 2021, 18 organizations and 577 individuals had been blacklisted in the country for financing terrorism under the United Nations Regulation No. 1 of 2012, according to the Defence Ministry. Through an Extraordinary Gazette Notification dated August 1, 2022, the Ministry of Defence removed six organisations and 316 individuals from the 2021 list, but added three new organisations and 55 new individuals to the list. Thus, as on August 1, 2022, at least 15 organizations and 361 individuals were blacklisted in the country. The organisations that were de-listed in the August 1, 2022, Notification included six international Tamil organizations – the Australian Tamil Congress, the Global Tamil Forum, the World Tamil Coordination Committee, the Tamil Eelam People’s Congress, the Canadian Tamil Congress and the British Tamil Forum. Of the 15 existing groups in the list, five are Islamist groups, including the NTJ, Jama’athe Milla’ athe Ibrahim, Willayath As Seylani, Darul Adhar alias Jamiul Adhar Mosque, Sri Lanka Islamic Student Movement and Save the Pearls.

According to the United States (US) Department of State 2023 Country Reports on Terrorism, Sri Lanka reported no terrorist incidents in 2023, but focused on strengthening counterterrorism (CT) frameworks and financial regulations. Sri Lanka joined key international CT initiatives, including the Combined Maritime Forces and Operation Prosperity Guardian. Sri Lanka assumed the 2023 chair of the Indian Ocean Rim Association, which lists CT as a key priority. While the LTTE remains dismantled, concerns persist over the Tamil diaspora, as well as ideologies and extremism within Muslim communities. Judicial proceedings for the 2019 Easter attacks continued, with 24 suspects on trial.

On July 26, 2024, the European Union (EU) extended its ban on the LTTE for an additional six months. The EU’s extension of the LTTE ban affirmed continued international support for Sri Lanka’s anti-terrorism framework.

Sri Lanka faces a growing challenge as a hub for narcotics trafficking. According to a January 6, 2025, report, the gross street value of narcotics and prescription drugs seized in operations conducted by the Sri Lankan Navy in 2024 was valued at over 28.158 billion Sri Lankan Rupee (SLR). This included more than 622 kilograms of heroin worth over SLR 15.554 billion in street value; more than 1,211 kilograms of Crystal Methamphetamine (ICE), worth over SLR 11.508 billion; more than 1,752 kilograms of Kerala cannabis worth over SLR 700 million; more than 119 kilograms of local cannabis, worth over SLR 23 million; and 1,179,746 units of prescription drugs, worth over SLR 373 million in the street.

The appointment of Anura Kumara Dissanayake as President and Harini Amarasuriya as Prime Minister in 2024 marked a significant political shift in Sri Lanka, reflecting a strong public mandate for reform and accountability. Both leaders are prominent figures from the National People’s Power (NPP), a progressive alliance known for its anti-corruption stance, grassroots engagement, and focus on social justice. Economically, the administration faces a challenging environment. While committed to renegotiating foreign debt and ensuring social welfare-oriented recovery, the leadership is under pressure to balance economic reforms with the expectations of a struggling populace. The government’s early moves toward inclusive policymaking and increased civic participation have been met with cautious optimism, both locally and internationally.

Overall, the political situation under Dissanayake and Amarasuriya is one of hopeful transformation, but success hinges on their ability to deliver results, manage economic pressures, and maintain stability while navigating entrenched political and institutional resistance.

While Sri Lanka has made notable strides in counterterrorism – evident in the absence of terrorism-linked fatalities in 2024 and its low ranking on the Global Terrorism Index – the nation remains vigilant against residual and emerging threats. In 2024, Sri Lanka’s security and political environments were marked by both resilience and complexity. Arrests linked to both IS-affiliated operatives and suspected LTTE sympathizers underscore the ongoing risk posed by extremist elements, both domestic and transnational. The government’s proactive measures – ranging from freezing assets of extremist-linked individuals and organizations to strengthening counter-terrorism efforts – demonstrated its continued commitment to national security. However, underlying ethnic and religious tensions, alongside regional geopolitical currents, necessitate sustained and balanced counterterrorism efforts to preserve national stability.

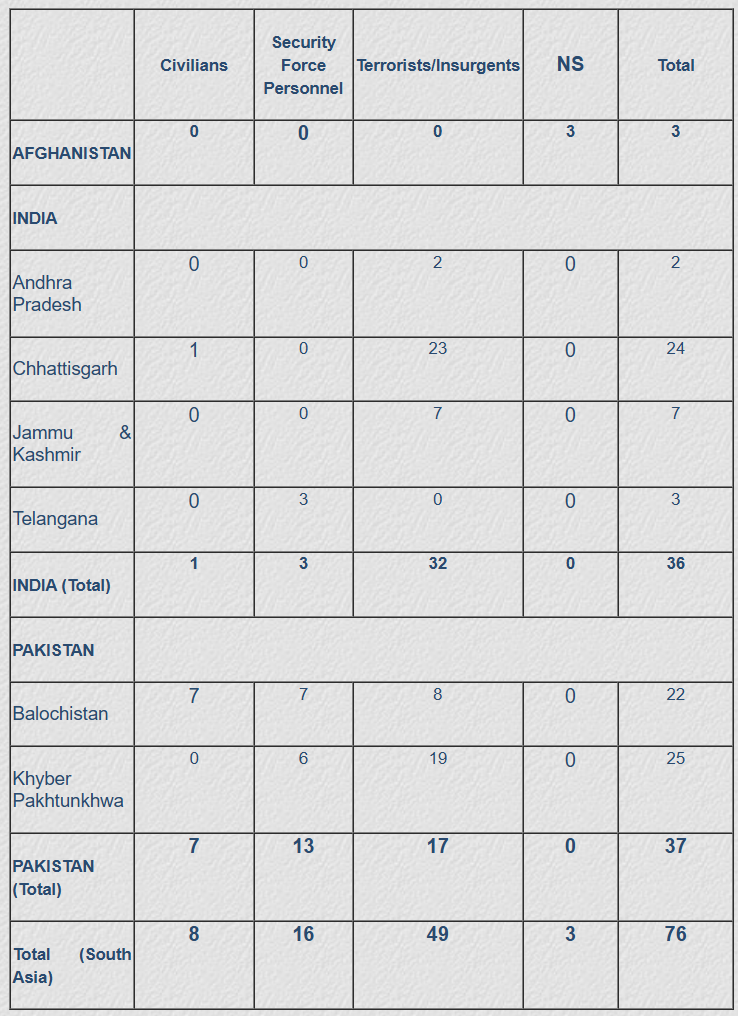

Weekly Fatalities: Major Conflicts in South Asia

May 5-11, 2025

Provisional data compiled from English language media sources.