Assessing The Taliban’s Connectivity Agenda In Afghanistan – Analysis

Since regaining control of Afghanistan in August 2021, the Taliban have been attempting to transform themselves from an insurgent group into a governing entity. Central to this transition is their ambitious plan to leverage Afghanistan’s geostrategic location at the intersection of Central and South Asia to become a regional connectivity hub. Investments in infrastructure projects aimed at reviving the country’s economy and integrating it into broader regional trade networks underscore this vision. However, these investments are shaped by complex political and economic factors, raising doubts about the Taliban’s capacity to fulfil their commitments.

Strategic Connectivity or Symbolic Governance?

The Taliban have initiated several connectivity and infrastructure projects in and around Afghanistan to project an image of effective governance. The financial model behind these developments remains opaque and questionable, with unclear funding sources and imbalanced budgetary allocations. Revenue is generated through public donations, local taxes—particularly from small businesses—and customs duties collected at strategically important border crossings. Despite the breadth of these revenue streams, the Taliban have not disclosed any official records regarding the collection and allocation of funds for public welfare. Furthermore, the regime’s growing reliance on domestic resource extraction exposes its fiscal vulnerability, exacerbated by the freezing of approximately US$ 9.5 billion in foreign reserves.

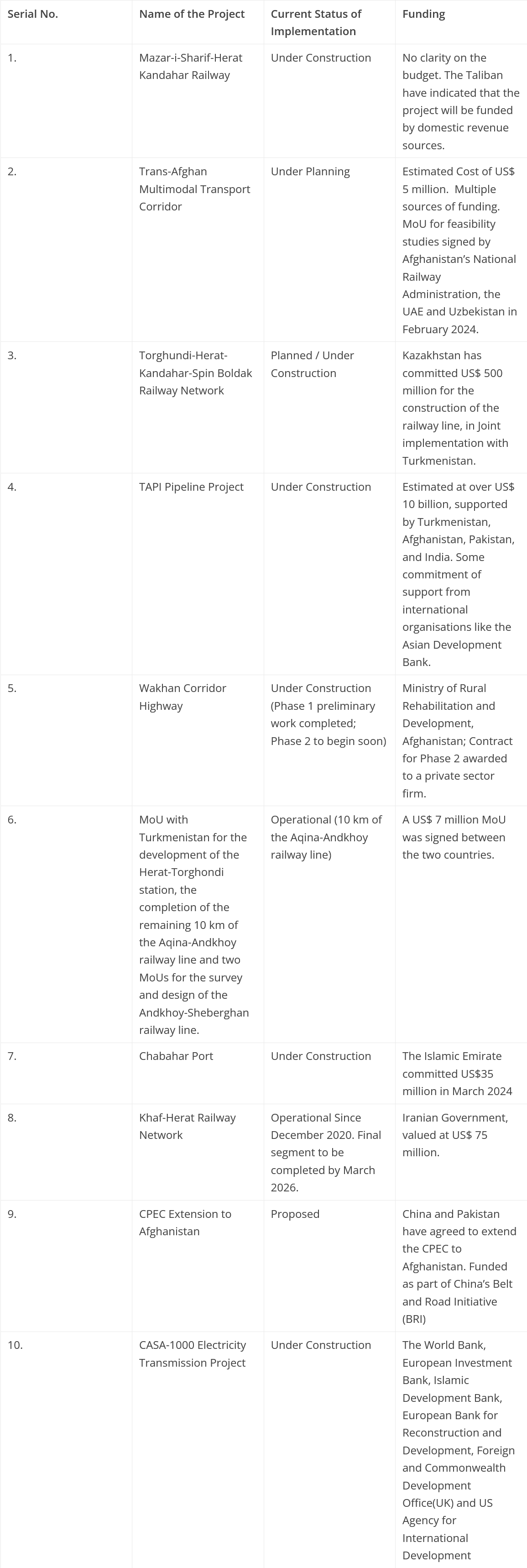

Table 1: Major Connectivity Projects Undertaken by the Taliban since 2021

The Taliban’s broader infrastructure strategy is centred on developing regional connectivity projects aimed at integrating Afghanistan into Central and South Asia’s economic corridors. As outlined in Table 1, the 1,468 km Mazar-i-Sharif-Herat-Kandahar Corridor—envisioned as Afghanistan’s “shortest and most economical” route connecting Russia and Central Asia with South Asia— aims to reduce cargo transit time between Uzbekistan and Pakistan to just 36 hours. However, the plan faces substantial obstacles, notably land disputes in Balkh Province, where farmers have faced uncompensated expropriation of agricultural land. Similarly, the Trans-Afghan Multimodal Transport Corridor, which aims to connect Uzbekistan, Afghanistan, and Pakistan, is being designed to carry up to 20 million tonnes of cargo annually. This initiative illustrates the Taliban’s barter-driven diplomacy, with Uzbekistan funding 45 percent of the Afghan section via exchanges of wheat and construction material. Once operational, the corridor is expected to transport up to 15 million tons of cargo annually by 2030, and cut down cargo transit time between Uzbekistan and Pakistan from 35 days to just five days.

The Islamic Emirate’s most significant step toward economic diversification has been its investment in Iran’s Chabahar Port. The US$ 35 million allocated to the Fakher Commercial Tower reduces Afghanistan’s dependence on Pakistan’s Karachi port. This connectivity drive is further supported by deepening trade relations with Iran. Under Iran’s “Five Nation Road” strategy—which links Afghanistan to European markets via China—the operationalisation of the Khaf-Herat railway (Table 1) has led to a 22 percent increase in dried fruit exports to Iran since December 2024. In response to Afghanistan’s economic pivot towards Iran, Pakistan imposed punitive tariffs at the Torkham border in January 2025.

Similarly, the Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India (TAPI) gas pipeline—412 km of which has been laid out as of January 2025—is projected to supply 5 percent of the gas to Afghanistan, and 47.5 percent each to India and Pakistan over a 30-year operational period. While the Taliban seek to position Afghanistan as a strategic actor within China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), security concerns have deterred major Chinese state-owned enterprises from investing in large-scale infrastructure projects.

Motives Behind the Connectivity Push

The Taliban’s aggressive push for regional connectivity is driven by a combination of political, economic, and strategic imperatives. Domestically, these projects serve as indicators of governance, compensating for the absence of democratic institutions by projecting the image of a functioning state. However, the Taliban’s funding model continues to rely heavily on public taxation, barter-based commerce, and informal hawala networks— factors that raise concerns about the long-term viability and sustainability of these initiatives.

Financial inefficiencies are compounded by the lack of regulatory oversight in barter-based agreements, where the partnering nation provides a significant share of project financing. Rather than direct financial payments, these agreements typically involve an exchange of natural or material resources. Moreover, such infrastructure initiatives offer economic incentives to tribal leaders and local warlords, thereby reducing the likelihood of internal conflict—a dynamic that may facilitate more coherent and stable governance. This economic co-optation strategy mitigates localised resistance and contributes to the consolidation of a more unified administrative structure.

The Taliban’s infrastructure projects have played a significant role in advancing their recognition by the international community and in facilitating Afghanistan’s integration into regional trade networks. By positioning the country as a viable and strategic transit hub, the Taliban aim to compel neighbouring countries—including China, Iran, and the Central Asian Republics—to engage with them economically.

To bypass Pakistan’s traditional monopoly over Afghan trade and commerce, the Taliban have redirected investments toward alternative trade routes, such as Iran’s Chabahar Port. Additionally, senior Taliban officials have announced their willingness to develop the Wakhan Corridor—a move aimed at diversifying economic partnerships and circumventing Western sanctions. However, the viability of these projects remains questionable, as tangible progress on the ground has yet to materialise.

Although there has been an overall decline in violence in Afghanistan since 2021, attacks targeting infrastructure projects have increased significantly, with local militias extorting contractors for so-called“protection fees” — a development that introduces an additional layer of instability. Infrastructure development plays a strategic role in aiding the Taliban to strengthen their internal control. Improved roads and transportation networks can help the group’s capacity to deploy military personnel and equipment quickly across different regions, and also enable them to respond more efficiently to security threats. In particular, such steps strengthen the Taliban’s counterinsurgency efforts against groups like the Islamic State Khorasan Province (ISKP). Diplomatic isolation presents another formidable barrier. Afghanistan’s exclusion from the global banking system severely restricts the regime’s capacity to conduct formal financial transactions. As a result, the Taliban have increasingly relied on alternative payment systems, many of which involve high transaction costs and reduced financial transparency.

Conclusion

The Taliban’s push for infrastructure development and regional connectivity is not merely about economic growth; it is a multi-layered strategy aimed at securing financial independence, political legitimacy, and regional influence. By enhancing Afghanistan’s trade routes, energy networks, and transit corridors, the Taliban is seeking to reorient the country’s economy toward non-Western allies while simultaneously reducing its reliance on Pakistan. However, internal instability, regional power struggles, and security threats continue to challenge the group’s ambitions. Whether Afghanistan successfully transforms into a regional trade hub or remains an unstable transit corridor will depend on how effectively the Taliban manages financial constraints, security risks, and diplomatic isolation.