Chinese Politics since Hu Jintao and the Origin of Xi Jinping’s Strongman Rule: A New Hypothesis

What is the origin of Xi Jinping’s strongman rule? A “victorious Xi” thesis argues that Xi simply won his fight to gain power. But this raises the question of where Xi found the political support to do so. A “collective support” thesis suggests that centralized power was willingly given to Xi by the Chinese Communist Party’s collective leadership to overcome the interest groups that were resisting reform. However, this leaves unanswered why the party oligarchs — who represented these vested interests — would be working against themselves in this way. In addition, such theories fail to explain why Xi took China down a path of Maoist conservatism after briefly flirting with reformism early on. Historical evidence points to a new hypothesis: that there was a “two-line struggle” between China’s conservatives and reformers that spanned Hu Jintao’s two terms and lasted into Xi’s early years. Xi’s source of power was initially reformist, but it was later replaced by collective support from conservatives.

Everything changed in 2012, the fateful year when Xi Jinping became the leader of the Chinese Communist Party. Xi’s throwback to Mao-style strongman rule is conventionally believed to be the driver of domestic change and a main source of tension internationally. However, our current understanding of Xi’s autocratic rise itself remains incomplete. One central puzzle is that, although Xi consolidated power rapidly and early, it remains unclear where he found his political support, or what his source of power was. If Xi was initially given collective support to fix problems that had arisen under collective leadership, and the ruling oligarchs were themselves part of the problem, how or why would they be willing to work against their own interests? If Xi’s strongman rule was truly consensus-based, why the bewildering policy contradictions during his early years in power? Finally, why did Xi’s personalization of power have to go hand in hand with a conservative approach to governance?

This article puts forward a new hypothesis to answer these questions, one that is based on the idea that there has been a “line struggle” (路线斗争) — a competition for supremacy between political actors who claim that they alone follow the correct party line — between China’s “conservatives” and its “reformers.”1 The two-line struggle examined in this article (2002–2017) is best viewed as a continuation of the left-right contestation in Chinese politics that started in the 1980s. This struggle did not end with Deng Xiaoping’s departure from China’s political stage in the late 1990s. It continued throughout Jiang Zemin’s reign and entered into a new phase under Hu Jintao — the latter fact has so far eluded most China watchers.

In China, reformers include both those who seek to get rid of the Chinese Communist Party and make the country a liberal democracy, as well as those who believe in the necessity of economic marketization, opening up to the outside world, and allowing some limited political reform that falls short of challenging the party’s supremacy. Conservatives oppose a market economy and political liberalization, usually in the name of safeguarding socialist orthodoxy, i.e., an economic system based on public ownership of property or economic assets, class struggle, and the party’s absolute control. In this paper, China’s conservatives are also interchangeably referred to as “leftists,” whereas the reformers are usually regarded as being on the right side of China’s ideological spectrum.

Xi took office in 2012 when China’s reformist (rightist) and conservative (leftist) forces were competing for political domination as well as fighting over which developmental model China should adopt. The reformist coalition had just regained the upper hand during the 18th Party Congress after years of rising conservatism that had gained momentum under Hu’s 10 years of leadership. Progressive programs were introduced during Xi’s early years in power (2013–2014), but the reformist comeback turned out to be ephemeral. The conservatives’ final victory over the reformers occurred around 2015. Xi’s successful personalization of power was part and parcel of this decade-long leftist vendetta. What is unclear is whether Xi picked the winning side, which then recast him in Mao’s image, or whether he had been part of the leftist fight from early on, driven by his own leftist disposition and beliefs, despite having been endorsed by reformers in the very beginning.

In short, this new hypothesis recasts the collective-support explanation for Xi’s rise as a struggle between the two major political groups in China. Xi’s source of power was initially reformist, but it was later replaced by conservative support. This helps to explain the policy contradictions of Xi’s early years, which reflected the unsettled left-right contestation. Once the conservatives finally won that battle, it was conservatism all the way for Xi.

This explanation is based on a revisionist interpretation of China’s recent political history. In this paper, I carefully examine a series of left-right disputes and challenge many conventional understandings of the trajectory of Chinese politics. In particular, I argue that Hu’s Scientific Outlook on Development (科学发展观) was more than a mere change in policy — it was a conservative political weapon for overriding Jiang’s Three Represents (三个代表). The Harmonious Society concept (和谐社会), usually seen as a second major party line proposed by Hu, was actually a reformist initiative to repackage Jiang’s theory in response to leftist critiques. The 17th Party Congress report witnessed an unmistakable leftist takeover: Jiang’s Three Represents were demoted, and the “Theoretical System” of socialism with Chinese characteristics (中国特色社会主义理论体系) became Hu’s de facto guiding ideology. The conservative force had become increasingly aggressive during Hu’s second term (2008–2012), but Jiang reemerged and made a call for reform in mid-2012. The reformist comeback did manage to put in place a progressive agenda at the 18th Party Congress and the 3rd and 4th Plenums. The Chinese Dream (中国梦), introduced in late 2012, was initially launched as a reformist project in order to neutralize leftist conservatism by promoting a sense of patriotic developmentalism. However, the effort failed. The reformers were finally subdued by the victorious conservative camp that stood behind a strongman: Xi, who gained his core leader status in 2016.

This two-line-struggle narrative challenges the conventional periodization of Chinese politics. Rather than three ten-year blocks — the Jiang era, the Hu era, and the Xi era — the Hu and Xi eras look more like a monolithic “long decade” that spanned Hu’s two terms and lasted into the early years of Xi. It only came to an end when Xi finally emerged as a consolidated autocrat around 2016. The final part of my empirical analysis demonstrates how the official documents of the party’s Central Discipline and Inspection Commission (中央纪律检查委员会) reveal the varying intensity of political tensions in Chinese politics over time.

This paper mainly relies on textual analyses of the Chinese Communist Party’s political discourses. Competing partisan voices found in publicly available official and semi-official sources, which provide context for one another, reveal the left-right struggle that ran beneath a public facade of political unity. I introduce a “layered publicity” model to conceptualize this logic of “autocrats going public.” It may be viewed as a social scientific foundation of the Kremlinology-style propaganda analysis. Theoretically, layered publicity enriches our understanding of the role of information in authoritarian politics.

The two-line-struggle hypothesis presented here opens up new space for rethinking some common assumptions about China’s domestic politics and foreign policy. China’s fateful change of course is conventionally believed to have its roots in Xi himself, but the reality may well be that the source is a “collective Xi,” i.e., the conservative coalition that empowered Xi. China’s domestic humanitarian crises and belligerent diplomacy will probably continue beyond Xi’s time. Insofar as conservatism is based in ideology, China’s all-around return to leftism is not so much about Xi’s personal ambition as it is about collective faith in the correctness of Maoism. Insofar as conservatism is driven by a fear of losing power that haunts the party’s ruling aristocrats, the demise of reformism under Xi invites us to seriously reassess some common-sense views in a counterintuitive way. It seems increasingly unconvincing to assume that Chinese rulers still regard performance-based legitimacy as necessary for regime survival. As opposed to the prevailing pessimism regarding the probability of peaceful and orderly transfers of power under authoritarianism, China’s next political succession will probably go smoothly, provided that the ruling cabal stays unified based on a shared dynastic belief in their right to rule China as the Red Descendants. In addition, policymakers who hope to grasp the rationale behind China’s foreign policy may want to consider to what extent China’s international aggressiveness is actually staged drama for domestic consumption.

The paper proceeds as follows. In section two, I provide a critical review of the existing literature on Xi’s rise to power. In section three, I discuss this paper’s methodological considerations and its theoretical contributions. Section four describes my analytical approach, the historical episodes that this paper considers, and the sources that I used. In section five, I present the episodes of left-right fighting. In section six, I briefly summarize the main findings and discuss the broad pattern of Chinese politics in light of the data extracted from the Central Discipline and Inspection Commission reports. The final section concludes with a methodological note on the study of Chinese elite politics.

The Rise of Xi Jinping

China observers have proposed two competing answers to the question of how Xi returned China to Mao-style strongman rule after years of collective leadership under Jiang and Hu: Xi simply defeated his opponents, in part because of an absence of sufficient constraints on his ambition, or he received collective support for his centralization of power. In this section, I critically review these explanations.

Existing Explanations

Some optimists once subscribed to the idea that Xi’s accession to the top party office in 2012 actually testified to China’s maturing political institutionalization.2 For all the possible factional horse-trading, the final pick of Xi was acceptable to all sides. It was essentially a top-down decision in line with past practices. It was allegedly an institutionalized procedure. Indeed, there is strong evidence suggesting this continuity: The way in which Xi was groomed as heir seemed to have been directly modeled on the pathway that prepared Hu to succeed Jiang. Xi’s political ascendance was celebrated as another peaceful leadership succession accomplished.

However, becoming the Chinese Communist Party’s general secretary is one thing. Becoming an autocratic strongman is quite another. While the former might have been the outcome of China’s partially institutionalized political process that presumably was still functioning by late 2012, Xi’s personalization of power was antithetical to the logic of institutionalization. Now that Xi has started his third term, anyone who tries to argue that his rule is just a strongman version of collective leadership will have many circles to square.3

The most straightforward explanation for Xi’s success in centralizing power is that he won the fight and wiped out his rivals by leveraging his informal political resources, such as political connections and factional bases, and by utilizing institutional tools that came with his formal office, including launching a large-scale anti-corruption campaign and creating the Leading Small Groups.4

However, analysts tend to argue that a major precondition of Xi’s victory was a lack of sufficient resistance. Without real political institutionalization that can enforce rules-based competition for power, the reemergence of Mao-style strongman rule should not be surprising.5 Xi also arguably took advantage of the power vacuum left behind after decades of unconstrained power politics that fortuitously sidelined all potential “princeling” rivals,6 descendants of China’s first-generation prominent revolutionaries who, like Xi himself, believe that they were born with the political credentials to succeed their parents to rule the country. In addition, the capacity of China’s political elders to oversee and influence the incumbent party leaders did look generally weaker under Hu than under Deng and Jiang.7 A window of opportunity was wide open to Xi.

In short, conservative and reformist policies coexisted in a confusing way. Such confusion raises the question of whether there was a unified collective patron who entrusted power to Xi.This “victorious Xi” thesis raises one important question: Where did Xi find the political support for his strongman ambitions? It is puzzling that Xi didn’t seem to have enough political strength to centralize power by himself, and yet it was done so early in his tenure and so rapidly, without any signs of intense power struggle or resistance.8 In fact, Xi’s power grab surprised everyone. For all the assessments after the fact that Xi had a dominant faction backing him,9 the fact is that a Xi coalition, if any, was not visible before the 19th Party Congress. As Li Cheng observed, Xi’s own basis of factional strength was weak during his early years.10 Without any revolutionary prestige or military credentials, Xi was once expected to be even weaker than Hu.11 Moreover, the conventional view that Xi consolidated power by promoting his own men, purging rivals in the name of anti-corruption, establishing new governing institutions, or playing one faction against another12 only further raises the question of how he was capable of doing so, no matter how weak the resistance was.

In response to this question of the source of Xi’s power, a competing explanation contends that, from the very beginning, Xi enjoyed collective support. According to this theory, Xi’s centralization of power was a consensus-based plan. Power was willingly bestowed on him by the party leadership, in the hopes that he could use that power to save the party from the crises that Xi’s predecessors appeared to be incapable of dealing with.13 In particular, the centrifugal force of the party’s collective, or oligarchic, rule, unrestrained by Hu, produced a set of interconnected problems: fragmentation of authority, stagnation in policymaking, widespread corruption among party officials, and worsening socio-economic inequality. Therefore, centralized power was a necessary tool to break the deadlock and save the reform of China from being hijacked by powerful interest groups.14

The collective support thesis does help to locate the source of Xi’s power, but it leads to a new series of questions: Why would the party oligarchs fight themselves for the regime’s well-being as a whole?15 If collective leadership itself was the problem, what made these top oligarchs willingly sacrifice their own power? The goal was supposedly to remove the vested interests that were standing in the way of China’s reform. Presumably, the party’s ruling oligarchs were connected to these interest groups,16 so what made them willingly forsake their own interests? If all the top leaders were able to work together and sacrifice their own parochial profits for the public interest, then any additional king-making efforts — establishing a strongman to serve as arbiter — would have been redundant.17 If the sacrifice necessary to save the regime was meant to be selective, who decided who would be the priests and who would be the burnt offerings placed on the altar?

Furthermore, the collective support theory has difficulty explaining some important empirical observations. First, if Xi was empowered by an elite consensus, what explains the policy contradictions during his early years in power? The party called for deepening marketization while further empowering the state-owned enterprises. It also advocated the rule of law while at the same time emphasizing the party’s unrestrained leadership and tightening up political control. In short, conservative and reformist policies coexisted in a confusing way. Such confusion raises the question of whether there was a unified collective patron who entrusted power to Xi.

There are multiple ways to square the circle, but none seem satisfactory. First, Xi could have been purely seeking power and did not have any policy ambitions.18 This possibility can be ruled out, if one’s starting point is the collective support thesis. Second, Xi might have been given executive discretion in policymaking: The collective support was mainly about granting political authority rather than micromanaging policymaking. In that case, any undesirable economic or social policies resulted from technical problems or difficulties and not political issues. Xi might have been balancing different interests in a rapidly changing situation.19 That he might have had to go through many trials and errors,20 or simply have been finding his way under uncertain conditions,21 made confusion and contradictions in his policymaking unavoidable. Or maybe some policy issues did not have a simple answer, and the still imperfect decision-making mechanism exacerbated the situation.22

However, reducing everything to the technical level does not explain the fact that the contradiction in question was a highly ideological one concerning the direction in which the country was being steered — socialist or non-socialist — not just which specific measures were being used. Here, a third view seems to offer a quick fix: The party aspired to have its cake and eat it too.23 The party wanted to uphold socialist principles while using the tools of reform. However, the rule of law and professionalism clash with the party’s desire for unrestrained supremacy and absolute control. Maintaining state intervention in the economy means that the market could never play a “decisive” role in resource allocation — an ambitious goal that the party put forward at the 3rd Plenum of the 18th Party Central Committee.

But this argument also runs into a problem: The mixture of reformist plans and conservative practice only lasted during Xi’s early years. After that, Xi’s policies became conservative in a Maoist fashion. Was Xi initially given collective support to break the resistance from vested interests and push China’s reform forward? This confusion poses a serious challenge to a fourth possible explanation: that policy contradictions existed because entrenched interest groups continued to defend their parochial interests against the central mandate. Top leaders who wanted reform were outnumbered by lower-level party cadres who were fighting every minor concession.24 It is argued that, in order to overcome the lingering resistance to reform, Xi’s power was further strengthened for the fight in 2017.25 However, the reality is that Xi finally emerged as a strongman and a conservative. Wasn’t his role as a strongman meant to push back against conservatism?

Here, let’s turn to the second empirical puzzle that the collective support theory cannot handle: Why did Xi turn hard toward conservative policies after a brief flirtation with reform? Again, existing views offer only incomplete explanations. One theory is that it was mainly about Xi’s own beliefs, ambitions, and choices.26 One variant of this “Xi-thinks-so” theory is that Xi was a conservative in reformist clothing — a “Gorbachev in reverse,”27 who fooled everybody in the beginning.28 Another variant highlights the tendency of bureaucratic over-compliance in a dictatorship.29 Once Xi was determined to embark down a conservative road, his followers over-did his bidding, thus making policy directives more conservative than intended. But this emphasis on Xi’s initiative and agency, plus the amplifying effect of sycophantic over-compliance, takes us back to the victorious-Xi question: What was the source of power that Xi relied on to become independent from the collective patron who gave him power in the first place? Another theory is that Xi’s conservative reorientation follows certain general logics of authoritarian governance rather than Xi’s personal decision. When reform began to erode political control, the party would not have hesitated to backpedal the process of political institutionalization and opening up.30 When political decentralization generated growth at the cost of threatening regime stability, the party would have reflexively brought back centralized governance, increasing control over local cadres and hedging against crises with renewed political legitimation.31 In Carl Minzner’s words, it is a “one step forward and one step backward” pattern in which the party always cannibalizes its prior reform for fear of losing power. However, this explanation causes new questions to arise: Why this timing and what triggered the change? If Xi’s first term started with a collective consensus on further reform, what caused the U-turn? And why bother with the back-and-forth during Xi’s early years in power?

Analyzing China’s Elite Politics: A Critique

There are two primary problems with existing theories of Xi’s rise. One has to do with the practice of theorizing itself: Key assumptions are not sufficiently justified and factual inconsistencies are not addressed. The other problem is methodological. In this regard, there are three general analytical shortcomings of the existing approaches to China’s elite politics: how factions are identified, distinguishing formal from informal power, and connecting the analysis of policy to that of elite power struggles.

Identifying Factions

Finding out who’s whose man — or identifying factions — is the most widely used method to track the changing balance of power in China’s elite politics. Factionalism is arguably an innate characteristic of China’s authoritarian system under the Chinse Communist Party’s rule — it is a mechanism for managing differences among political elites where institutionalized procedures are either missing or act as mere window dressing.32 Factionalism can be driven by multiple factors: ideology, pursuit of power, bureaucratic interests, or a combination of all three.33 Analysts usually identify factional links and networks using party leaders’ resumes and bios, under the assumption that certain factors — birth place, kinship, friendship, educational background, and, most importantly, work experience — may help to bind individuals together politically.34

However, accurately discerning factional ties is a constant challenge. The observable indicators that suggest that factional ties exist do not necessarily reveal real ties, which are often unobservable.35 Moreover, politicians often have multiple biographical facts that may place them into different factions. Worse, factional affiliations may change over time, as power within the top leadership is constantly realigned.36

Diverse judgments in identifying faction membership have led to many different configurations of the distribution of power and factions within the central leadership (e.g., the Politburo).For these reasons, existing analyses yield mixed, sometimes conflicting, results. There are many controversial cases of scholars identifying certain party leaders as belonging to a particular faction. For instance, can we really count Wen Jiabao, Li Yuanchao, Liu Yunshan, and Wang Yang as Hu’s men? Did Zeng Qinghong and Wang Huning shift their loyalty from Jiang to Hu? Did Zhou Yongkang and Li Changchun belong to Jiang’s faction? Is it really possible for Wu Guanzheng and Yu Zhengsheng to stay neutral and have no factional affiliations? Most importantly, which faction did Xi belong to before he assumed the top office?

Diverse judgments in identifying faction membership have led to many different configurations of the distribution of power and factions within the central leadership (e.g., the Politburo). Key issues include whether Hu’s Youth League Faction ever existed, whether Jiang’s coalition, initially known as the Shanghai Gang, still held influence throughout Hu’s entire reign and during Xi’s early years, and, ultimately, who belonged to which camp. These questions lead to the third problem: whether China’s political elders, such as former party secretaries, retired Politburo members, and even some first-generation communist revolutionaries who are centenarians, remain politically relevant. If so, how much power do they have? Relatedly, the party’s general secretary may not necessarily serve as the head of a faction, because real power may be held by those who do not hold formal offices.

Formal and Informal Power

It has been a perennial challenge for scholars of authoritarian politics to tell how much of a political leader’s power is based on his or her formal position and how much is based on informal sources of power. China scholars have not found an effective formula for doing the calculation accurately.37 A common problem is that scholars sometimes arbitrarily or selectively point to certain leaders’ reliance on formal authority, when their informal sources of power, if there are any, are hard to identify. A good case in point is the various interpretations around Xi’s source of power, as mentioned above.

The existing literature has correctly noted that formal and informal political power interact in a complex manner.38 However, simply recognizing this interdependence is not enough. The ability to locate the source of real power is still wanting, not least because of the opaque nature of authoritarian politics that makes relevant information inaccessible.39 For all of the advantages that may go with the formal office of the party general secretary — access to symbolic, bureaucratic, and material resources, and control over agenda-setting and personnel40 — precise judgments regarding whether the party’s top leader relies primarily on formal sources of power or informal ones remain elusive. For example, Jiang’s successful consolidation of power is attributed to both his political skills in building up informal factional support and the authority of his formal office,41 but which force played a more decisive role? Moreover, the level of authority that a formal position carries may vary over time. If formal power prevailed over informal power under Jiang,42 it was obviously no longer the case for Hu, who is conventionally regarded as having been much weaker than Jiang.

Politics Versus Policy

That policy and elite power struggles in authoritarian China are intertwined — that policy disputes can cause elite splits and that political struggles can clear the way for policy changes — has long been a leitmotif one encounters when reading about Chinese politics under Mao and Deng. Unfortunately, the study of China’s elite politics has become increasingly detached from analyses of China’s economic and social policies. Leadership succession and political appointments in post-Deng China seem to have nothing to do with how China is governed and seem to be all about infighting and quarreling among the political elites behind the scenes. Beneath this illusion lies a belief that was once widely shared until Xi’s rise: that China would continue to walk the Dengist path of reform and that elite politics are only relevant insofar as they determine who would lead this effort.

The recognition that China’s reform has, in effect, ended under Xi’s conservative rule has nevertheless not brought back the analytical approach that emphasizes how deeply policy disputes can be embedded in elite power politics, and vice versa. After all, it is convenient to attribute all policy changes to Xi’s personal beliefs and choices. It is also convenient to use the factionalism approach to explain how Xi defeated his rivals. This is usually done by coding Chinese leaders’ bios and resumes, and proposing hypothetical factional configurations that support the theory that Xi won because he was more politically connected than his rivals. For such a network-based approach, policy issues are anything but analytically relevant. Veteran China analyst Alice L. Miller has lamented that the ongoing factional analyses of elite politics has produced little insight into China’s policymaking.43 Some claim that policy disputes can neither cause nor explain elite struggle in an authoritarianism system.44 I argue just the opposite.

Policy disputes are closely connected to authoritarian elite politics in at least two ways. First, policy preferences reflect a person’s judgment on which approach to governance (e.g., how the economy is managed or how resources are distributed) best serves that person’s interests. Such judgment is often ideologically based. Thus, policy differences can easily develop into elite conflict, considering that policy can be intrinsically linked to one’s short-term or long-term interests.45 Second, partisan statements on policy preferences can be used strategically as a public signal or rallying point for political mobilization.46 To keep a public facade of elite unity when engaged in a power struggle, authoritarian rulers may want to use indirect means of political communication. Policy disputes are one such type of camouflage. It is not necessary for politicians to truly believe in the value of a policy or an idea in order to defend it in the political arena. Policy differences can be voiced purely for the sake of opposing political rivals.

Using Public Information to Decode Authoritarian Elite Politics

A new approach to studying elite politics should address the question of how to systemically track authoritarian elite politics, which is usually shrouded in deep secrecy, by examining public information. This section prepares the theoretical and methodological ground for doing so. I begin by setting up a theoretical framework for thinking about why and how authoritarian elites use public media under different scenarios depending on whether information is under state control and whether elites in a political struggle are trying to maintain the regime’s control over society. Existing literature gives only a static picture of authoritarian elite politics and does not give due attention to the fact that public information may be a window through which we can understand politics under authoritarianism, something usually kept secret by the ruling elites. I propose a “layered publicity” concept as a theoretical foundation for the Kremlinology-style analysis of authoritarian propaganda and related official publications. This classical, interpretive method of studying authoritarian elite politics makes it possible to uncover the behind-the-scenes stories of political struggles by reading what autocrats circulate in public.

Public Information and Authoritarian Politics

Information interacts with autocratic politics in a number of ways, depending on with whom authoritarian rulers are dealing — society or political elites47 — and the extent to which the authoritarian regime has control over the flow of information. Autocrats either consciously use publicity to consolidate their rule when the flow of information is under state control, or they passively react to the challenges brought by information that is beyond their control.

There are four different scenarios of how information and autocratic politics interact. When an authoritarian regime has lost control over public information, there are two possible outcomes: Political infighting becomes visible to the public (Scenario I), or anti-regime dissension can be heard from non-governmental political opposition in the public sphere that was once dominated by the authoritarian state (Scenario II). When the flow of information is still firmly under state control, the authoritarian regime manipulates public communication and mass media to govern, by producing propaganda and engaging in censorship (Scenario III). Unsurprisingly, the ruling elites use the same set of tools against their elite opponents during power struggles (Scenario IV).

These scenarios are analytically distinct, but in reality the boundaries are not so clear-cut. Infighting among ruling elites often interacts with mass activism — high politics seldom stays detached from governance. In addition, in practice, there is no complete control of information. Moreover, the state can adapt and react quickly in order to harness an information flow that is temporarily out of control. State control over political publicity — the manipulation or use of public information for political purposes — is a function of regime strength and capacity.

The following subsections elaborate these four scenarios by situating each within relevant literature on authoritarian politics. We will see that the ways in which information and publicity influence autocratic politics follows the underlying logic of the Rebel’s Dilemma: Politics is basically about the struggle over solutions to the collective action problem.48

Scenarios I and II: Loss of Control

Scenarios I and II describe situations in which political publicity is beyond state control or is unintended, in the sense that, from the state perspective, such uncensored and unrestricted flow of information poses serious threats to the regime’s survival.

In Scenario II, unintended publicity can be the result of a temporary breach of the state’s general authoritarian control of society. The state may renege on an earlier decision to open up society politically or economically, which required unrestrained information, and backpedal to tighten control when threatened. This could happen if the state feels that too much political security was traded for giving society the freedom necessary for socioeconomic development.49 Also, new technologies, such as social media or AI, usually cause a sudden breach of this kind. When new modes of communication become available, they offer new ways to circumvent the old information roadblocks that the authoritarian state has put in place to deter collective action. However, a strong autocratic state with learning and adaptive capacity can quickly catch up and harness these technologies. The internet initially carried much hope of fostering democratization in China, but ended up becoming an authoritarian tool that has arguably made the Orwellian world of 1984 come true.

“Unintended” publicity generally refers to the flow of information that is out of the state’s control. Unlike when the state selectively promotes voices within society, here the independence of social forces is much more secured because the state is no longer strong enough to eradicate non-state forces and control information. Lacking sufficient state capacity,50 a weak autocratic regime often seeks to co-opt political challengers through formal quasi-democratic institutions, e.g., legislatures.51 In this case, deal-making, negotiating, and bargaining is done behind the scenes without the public’s knowledge. In effect, with such political institutionalization (i.e., establishing rules and regularizing political participation), a weak autocracy tries to exert limited control over information about politics to the best of its ability.

Just as elite cohesion is necessary for autocratic stability, elite disunity — in the form of a split, defections, or political realignment — supplies favorable opportunities for popular revolt.Whereas autocratic elites still appear unified in Scenario II, they no longer are in Scenario I. In this scenario, political infighting within the leadership is laid bare for the public to see. Such political publicity is “unintended” in the sense that, from the perspective of the once unified state, elite disunity is something undesirable and detrimental to the regime’s survival. Warring elites are crippled by their irreconcilable differences and their inability to settle disputes behind the scenes, which is what leads to their fight coming out into the open.

During an open confrontation, the propaganda machine that previously targeted the populace is now being deployed by contesting factions against one another. Through the use of persuasion/denigration of opposing factions and the projection of power, factions fight to win over potential allies and deter them from joining their opponents by influencing their calculation of risks, cost, and benefits. The goal is to undermine an opponent’s capacity to organize, coordinate, and sustain collective action while enhancing one’s own political mobilization.

When a weak autocratic regime is plagued by either elite strife or opposition from society, or both, it’s possible for Scenarios I and II to overlap. Mass mobilization may exert substantial influence on the unity or disunity of the ruling autocrats. How political elites perceive the regime’s survivability factors into their calculus for deciding whether or not to defect, as their future spoils depend on the regime’s survival.52 Increasing the visibility of mass activism may help elites to cooperate and overcome the collective action problem that is caused by authoritarian elites receiving imperfect information.53 By virtue of its signaling function, mass opposition has the potential to create new political opportunities — i.e., it can deepen both popular and elite threats to the regime.54

On the other hand, the degree of elite unity makes mass activism more or less likely. Intra-elite struggle influences potential rebels’ perceptions and assessment of the regime’s strength.55 Just as elite cohesion is necessary for autocratic stability,56 elite disunity — in the form of a split, defections, or political realignment — supplies favorable opportunities for popular revolt.57

Scenario III: Using Information to Manipulate the Public

Existing literature is most developed regarding Scenario III, in which the state retains control of the flow of information and uses it to target society. Authoritarian governments are often not transparent, because they face little to no accountability. Nevertheless, autocrats do not seek to operate under total secrecy. Rather, certain types of publicity can contribute to the resilience of autocratic rule.

Propaganda is a common authoritarian tool for reducing the cost of ruling, given that coercion-based governance is not sustainable in the long run.58 Propaganda usually works hand in hand with censorship. The latter removes “dangerous” information and diverts public attention, thus clearing the ground for “healthy” indoctrination via the former.59

In addition, autocrats need to regularly showcase their power to remind their subjects that they would not have a chance in a revolt. Projecting an image of elite cohesion or demonstrating political strength and “invincibility” may help check expectations among the people that a rebellion could lead to any really change.60 This psychological technique of deterrence makes anti-regime mobilization difficult by preventing the emergence of a public platform that could be used to rally and coordinate potential followers,61 and by intimidating potential rebels who are planning an organized uprising.62

Public political rituals, such as mandatory attendance of state-organized ceremonies, are necessary and useful for keeping citizens with anti-regime attitudes from fully realizing how many political allies they might have. Even if the anti-regime attitude is widespread, it is not a real threat to a ruler so long as people don’t know that they have potential allies who think like them.63 When compliance is the only thing visible in public, as a result of propaganda and censorship, it destroys the basis for a shared expectation of collective action.64

Autocrats also need to gauge the level of threat they face from society by allowing some non-governmental voices to be heard. The more powerful dictators become, the less information they have about negative views of the regime, because any sincere expression of discontent makes one a potential anti-regime revolutionary in the eyes of the ruler.65 Furthermore, autocrats are hampered by the perennial principal-agent problem when it comes to holding their subordinates accountable. Local officials are systemically incentivized to manipulate information to only report good news and to hide their own failures.66 To detect governance problems and monitor local agents, autocrats may strategically open up a controlled space in which people can voice complaints about policies, criticize bureaucratic dysfunction, or report on local officials’ wrongdoing.67

Finally, a minimum level of freely circulating information is necessary for economic development, which is the foundation of performance legitimacy. Dictators are thus faced with a trade-off between political security and economic growth. Relaxed authoritarian control brings wealth, but it also makes people more politically enlightened and empowered, capable of resisting the regime.68

Scenario IV: The Role of Information in Elite Power Struggles

In contrast to Scenarios I, II, and III, Scenario IV — in which elite politics play out when the state has control of the flow of information — is relatively undertheorized in regard to how and why the dissemination of public information plays a role in elite power struggles. Obviously, authoritarian secrecy that keeps elite politics away from public knowledge is the biggest obstacle to a systematic understanding of elite politics.

One major analytical focus of existing literature is authoritarian institutions. Scholars have explored the ways in which institutions and institutionalization may help autocrats to solve the central structural problem of autocratic leadership: power sharing. When the most powerful individual among the ruling elites (usually the dictator) assures his colleagues that he would not try to concentrate power at their cost, how can they be sure that he will keep his word?

This problem of credible commitment exists in all forms of human politics,69 but it is further compounded under autocracies, where there is no third-party referee to enforce any agreement, and violence always serves as the ultimate arbiter.70 These two characteristics of authoritarianism make credibility a scarce commodity among the ruling elites. Furthermore, political secrecy is more than a mere manifestation of autocratic fetish for control. While it helps autocrats to guard against potential attacks from within, this tactical “blindness” cuts both ways: Secrecy simultaneously empowers and debilitates all players.

Scholars have argued that information and publicity may alleviate this credible commitment problem by means of authoritarian institutionalization. Regularized interaction among political insiders and formal rules, such as establishing a legislature or term limits, facilitates information sharing and brings about more transparency. Unnecessary misunderstandings can be avoided, negotiations made, transaction costs reduced, conflicts mediated, individual ambition bridled, and everybody’s cost-benefit calculation directed toward long-term cooperation.71 Furthermore, formal rules stand as publicly observable signals. They act as monitoring devices that help detect deviation from and noncompliance with the power-sharing pact.72

While some formal rules inevitably have to be formally written down and enshrined, not all rules regulating political interaction at the top have to be made known to the public.However, it is the balance of power, rather than informational devices, that ultimately make a power-sharing pact sustainable.73 There must be a credible threat of removing the dictator.74 Such credible constraints exist only when institutionalization changes the distribution of power.75 Credibility has to rely on successful collective action by a unified coalition of ruling elites, which in reality is hard to come by due to factionalism, dictators’ divide-and-rule strategy, and a general risk-averse attitude among politicians under conditions of uncertainty.76

The institutional approach to authoritarian elite politics is limited in two aspects. First, it is silent as to how political struggles between autocrats play out. While a struggle for power is presumably a dynamic process, the institutional approach paints a static picture. It theorizes under what conditions (balance of power) a power-sharing commitment can truly be credible, but it has nothing to say about the trajectory of the struggle. How can we possibly track the process of political infighting if it is a moving target?

Second, unsurprisingly, the institutional approach by definition focuses on how information generated by certain political institutions can be useful for managing elite politics. But it pays little attention to a more common sensical type of information — what autocrats say and write — thus leaving unexplored the possibility that authoritarian elites do make use of public media in power struggles. This analytical negligence is most likely a result of a conventional assumption that autocrats try to avoid any publicity that showcases internal disunity, except when the regime is so weak that the situation is out of control. Information, as the institutional approach suggests, does not have to be public or publicized when it plays a role in structuring political expectations. While some formal rules inevitably have to be formally written down and enshrined, not all rules regulating political interaction at the top have to be made known to the public.

Layered Publicity

I argue that autocrats leverage public channels of information when engaged in political infighting.77 By following these public clues, we may be able to garner a more complete understanding of the trajectory of intra-elite power struggles. To theoretically demonstrate how autocrats “go public,” I introduce a model of “layered publicity.”

Layered publicity presumes that there is a public sphere under autocracies. However, it is an expanded notion of the public sphere, in which there is a neutral space for public information and there is not an intrinsic association with democracy.78 Instead, an authoritarian public sphere presumes state control over information, to varying degrees.

An authoritarian public sphere is layered in the sense that not everyone has equal access to all parts of the public space. Certain parts of the public arena are reserved for specific purposes and only open to political insiders. This autocratic public space is also hierarchical, insofar as power is hierarchically distributed under authoritarianism. The more authoritative that one particular layer is (i.e., the closer it is to the pinnacle of power), the more restricted the access.

There are two important things to note about layered publicity. First, not everyone has the right to publish at every level in this space. Making one’s political voice heard through a certain type of media outlet (e.g., central-level party mouthpieces) requires a politician to have a certain amount of political strength. Second, communication at higher levels often involves the use of an encrypted language that is shared exclusively among political actors.

The question inevitably arises of why autocrats do not simply use internal information channels for political signaling. Why do they have to make it publicized — yet encoded — so that ordinary citizens are kept ignorant of what is really going on?

The answer is that the authoritarian public sphere is intrinsically a field of power. To use it requires political strength. Access is available to the powerful only. Getting one’s voice heard in public is a demonstration of power. Silence itself signals weakness. This logic is commonsensical when applied through a state-society perspective. Here, this logic is still applicable as public information now targets political elites rather than the public. When internal channels no longer provide sufficient leverage for projecting power, political elites have to go public.

A few caveats are in order. First, the typical pattern of layered publicity under a closed authoritarian system, such as the Chinese party-state that maintains a near totalitarian control over the society, should be expected to differ from layered publicity under an electoral authoritarian state in which autonomous political opposition exists. How political infighting spills over into the public view and how political elites consciously leverage publicity to win power struggles should take drastically different forms. Key factors include the effectiveness of autocratic control and the role of elections. Second, elite politics is a multi-dimensional activity. Political struggle involves much more than just public polemics and signaling. Third, layered publicity does not suggest that we can know everything that is going on behind the scenes by analyzing publicly available data. A large part of autocratic politics remains hidden.

Interpreting Political Texts

If intra-elite power struggle is a multi-dimensional phenomenon, layered publicity allows us to examine one aspect of it that is observable: the ideological/discursive contestation that goes public via state media and semi-official channels.

“Propaganda analysis,”79 or what is commonly known as “Kremlinology” — or “Pekingology” in the case of Chinese politics — is ideal for examining Chinese elite political elites for two reasons. First, the regime uses state media for political purposes. Second, official channels of information are under state control. Because of these two facts, the content of official state publications and propaganda can be viewed as truly reflecting what is politically significant. For this approach to be fruitful, researchers must be very familiar with relevant political discourses of both the past and present — i.e., their knowledge should be “comprehensive” and firmly based on “long memories.”80

Another major methodological concern with the Pekingology approach has to do with who has the correct interpretation of the texts in question. Analyzing propaganda is, by its nature, subjective. Nevertheless, it can still shed light on elite power struggles for a few reasons.

First, interpretation is inevitable in all social sciences. Even quantitative techniques do not guarantee objectivity. For example, counting is based on categorizing.81 One makes a qualitative judgement when assigning similarity or significance to things.82 To be sure, the quantitative approach to textual data is mainly justified on the ground that it is beyond human capacity to read all the texts in the age of information overload. It is never intended to replace human understanding.83

Conversely, without the big picture, it is impossible to identify what is politically significant in the swirl of information.Second, if interpretation is unavoidable, we must then determine how to distinguish the bad interpretations from the good ones. Words and phrases in political texts provide the empirical bedrock and set up the boundaries for how far astray interpretations can go.84 Competing interpretations are evaluated by how coherently they organize facts into a whole without inconsistencies. An interpretation can be “falsified” by a new narrative that introduces new facts and provides a better way of relating facts to one another.85

Third, Pekingology has been successful in the past.86 For example, it captured the political dynamics of the Soviet-China split and tracked the twists and turns of China’s Cultural Revolution.

In short, when conducting Kremlinology-style textual analysis, context matters. Context may refer to the macro-level political landscape, or to a limited universe of relevant texts. When it comes to layered publicity, one general pattern we will see is mutual contextualization: Without being familiar with the discourses circulating in the lower layers, it is impossible to make sense of the most authoritative discourses in the top layers. Conversely, without the big picture, it is impossible to identify what is politically significant in the swirl of information.

Research Design

A Discursive Approach

In this paper, I conducted an interpretive textual analysis of relevant political texts in order to identify elite disagreements and policy changes in China since 2002. I did so by tracing the variations or deviations in the use of certain key words and phrases and discursive patterns in official narratives. I measured the power balance by making context-based qualitative judgements — such as determining which camp dominates the agenda setting, which camp controls the de facto framing of political ideologies, whether political elites’ intended goals are fulfilled or thwarted, or how antagonistic their initiative is and how forceful is their rivals’ counteraction.

I do not attempt to determine particular leaders’ political affiliation by assessing what they said or what was published under their names. The true relationship between a leader as a nominal author and a political text is sometimes hard to know. It is possible that top leaders sometimes do not have full control over official texts, especially when he or she is a mere figurehead. Therefore, the analytical focus is on the texts themselves. The identification of political fault lines is mainly based on the detection of competing discourses. For example, both Hu and Xi were found to have nominally authored and endorsed both reformist and conservative messages. It is hard to judge their sincerity in each case, but what matters here is that the mixed signals sent under their names point to the ongoing political contestation, or the absence of political domination by one camp. While there are many reasons to believe that Hu and Xi actually sided with the conservative camp, this fact is analytically secondary in this line struggle narrative.

By delinking the analysis of power from political offices, this discursive approach makes it possible to avoid the formal-informal problem described above. We can simply look at the power distribution at a certain time as reflected in political texts. There is no longer any need to figure out the exact combination and interaction of informal and formal authority that produced the final outcome.

This discursive approach naturally highlights the non-trivial role that policy plays in politics. Polemics usually center on policy and governance issues, either because they are the actual issue at hand, or because they are discursive tools that are being used for political signaling. By studying elite politics, we can learn about policymaking, and vice versa.

The Episodes

I focus on six major “battles” of this “war” between left and right that spanned Hu’s two terms and lasted into Xi’s early years.

The debate on “human-centeredness” and the struggle over the political status of the Scientific Development concept;

The struggle over the meaning of the Harmonious Society concept;

The struggle over the political discourses of the 17th Party Congress report;

A conservative shift in the discourse on the “Soviet lessons”;

Jiang’s rallying call before the 18th Party Congress; and

Competing framings of the Chinese Dream during Xi’s early years.Each episode reveals the status of the left-right struggle and the relative power balance at that time. By looking at these cases all together, a trajectory emerges. To be sure, these episodes are not “cases” in a social scientific sense, i.e., a small number of units selected for the purpose of understanding a larger class of similar units.87 Instead, they are historical snippets selected to piece together a large historical picture, by virtue of the political and historical significance of the events covered by each episode. In particular, episodes 1, 2, 3, and 6 center on the major party lines/ideological projects that were underway during Hu’s and Xi’s times in power. Episodes 4 and 5 focus on two political initiatives adopted by the two contesting camps, which marked two watershed moments during this power struggle.

These narratives are complemented by a content analysis that tracks the varying intensity of political tension over time. The original data used here is generated by coding the textual positions of the term “political discipline” (政治纪律), which appears in all of the official reports of the Chinese Communist Party’s Central Discipline and Inspection Commission, and the types of issues that “political discipline” refers to in each case. Together, these analyses enable us to identify important trends and milestones in the trajectory of Chinese politics.

The Texts

In accordance with the idea of layered publicity, I only analyzed publicly available sources, and I selected political texts from different “layers.” Below is a list of sources used:

Publicly available texts of party congress reports and plenum resolutions;

The officially compiled anthologies of party documents;88

The selected works of top party leaders;89

Articles published by top party mouthpieces;

Propaganda materials published by major party-affiliated publishing houses;

Works published by leading party theoreticians via semi-official channels.Data from three particular sources are worth a more detailed introduction. They are not only records of politics, but also part of politics. First is the Qiu Shi (秋石) article series, which was published by the top party journal Qiushi (求是). Qiu Shi is a pseudonym, or a literal transmutation that phonetically corresponds to the name of the journal itself, indicating the authoritativeness of its voice. The Qiu Shi articles were created in 2002 for the purpose of promoting Jiang’s new ideological program.90

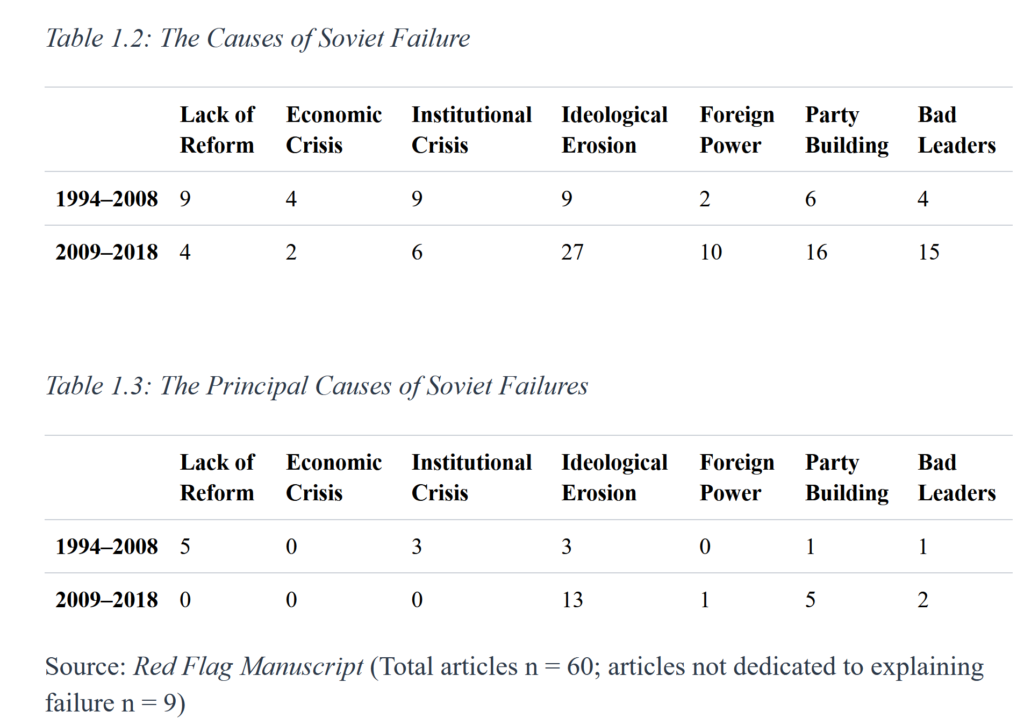

Articles were also analyzed from the Red Flag Manuscript (RFM 红旗文稿), which was sponsored and managed by Qiushi.91 Previously called Internal Manuscript (内部文稿), the Red Flag Manuscript obtained its new name in 2003. The new name naturally evoked the Red Flag (Hongqi 红旗), the top party journal under Mao which later became today’s Qiushi. In 2009, the Red Flag Manuscript went through a “total remodeling” (全面改版).92 Since then, it has become the flagship mouthpiece for conservative voices in China. Some Red Flag Manuscript articles directly influenced the formulation of major party lines and policies under Xi. For instance, Xi’s “cultural confidence” (文化自信) was originally proposed and elaborated in three Red Flag Manuscript articles in 2010.93 Foreshadowing what Xi would be doing down the road, another Red Flag Manuscript article made a belligerent call for “the People’s Democratic Dictatorship” (人民民主专政) in 2014 as a conservative response to the reformist agenda on the rule of law put forward at the 4th Plenum of the 18th Chinese Communist Party Central Committee.94

The Marxism Project stopped publishing such official materials in 2008. The most reasonable explanation is that the Red Flag Manuscript became the conservative headquarters in 2009.The Red Flag Manuscript editors also published a book series called Analyzing the Theoretical Hot Issues: Selected Articles of the Red Flag Manuscript (理论热点辨析: 《红旗文稿》文选). The series published one book every year from 2009 to 2017. Each was a collection of Red Flag Manuscript articles picked by the journal’s editors. This was a way to signal to people which were the most important articles.

The third notable source is the print materials produced by “The Marxism Project” (马工程), an abbreviation for “The Marxism Project for Theoretical Study and Theory-building” (马克思主义理论研究和建设工程) launched in 2004.95 According to Li Changchun (李长春), who was then a Politburo Standing Committee member in charge of ideological work, the Marxism Project was important for “consolidating the leading position of Marxism in the ideological field.”96 Li warned against “capitalist liberalization” (资产阶级自由化), the political crime that Hu Yaobang and Zhao Ziyang were charged with in the 1980s.97 The message was clear.

From 2004 to 2007, the Marxism Project officially produced seven books split into two series. The first series was called The Marxism Project for Theoretical Study and Theory-building: Selected Reference Materials, mainly a collection of academic writings by party theoreticians.98 The second series was called The Marxism Project for Theoretical Study and Theory-building: Selected Research Reports, which collected original short reports written by research teams on assigned topics.99 The Marxism Project stopped publishing such official materials in 2008. The most reasonable explanation is that the Red Flag Manuscript became the conservative headquarters in 2009. Launched by the party center, the Marxism Project was not a platform that could be exclusively used to promote leftism. Indeed, it contained a mixture of both leftist and reformist voices. The following analyses will draw heavily on the articles from both of the Marxism Project series.

Chinese Politics since Hu Jintao: A Revisionist Sketch

The two-line struggle that I examine in this article did not actually start with Hu. It is a new chapter of the unfinished left-right struggle that dates back to the early reform period under Deng and which continued throughout the Jiang era. This part of the two-line struggle’s history has been well documented.100 In the post-Mao era, the main fault line has been whether China should stick to the path of socialism, or depart from it and embark on a road of development guided by a market economy and democracy, broadly defined.101 The leftists, who firmly champion socialism, usually call the reformers “rightists” (右派), which carries a strong derogatory connotation. The left-right labels go back to the communist and socialist movements in Europe beginning during the Industrial Revolution. The left has a strong association with class conflict. It is also a political-cultural legacy of the Maoist past, featuring waves of struggles against the so-called counter-revolutionary rightists. Hence, the leftists generally feel more comfortable with being called leftists (左派). Defined in relation to the rightist enemies, the name “leftist” is traditionally associated with political correctness and a sense of mission to safeguard revolution and socialism, especially in the Mao era.102

That the political legitimacy of leftism in China still stands unchallenged in the reform era, however, is evident from how official party documents describe radical Maoist leftism during the Cultural Revolution. Specifically, when they refer to “leftism” within quotation marks (“左”),103 it is in order to denote something that should be denounced, i.e., Mao’s mistakes, and distinguish it from what should be retained — the party’s socialist foundation. Thanks to the political cover offered by putting leftism in quotation marks, the post-Mao leftist elites could appear to be walking a middle way, upholding the socialist orthodoxy against both Mao’s radical anti-bureaucrat stance and anti-socialist rightists. But at its core, socialist orthodoxy is unmistakably leftist in terms of its constituting principles and elements, such as the worldview that capitalism is undesirable and class struggle is the foundational truth. The fact that there are now “two” leftisms, which allows party leaders to criticize the Maoist past while retaining socialist orthodoxy, is arguably the ideational foundation of a prudential rule in the Chinese Communist Party: “Better to stay on the left than to go to the right” (宁左勿右).

From a macro perspective, the trajectory of China’s reform and opening-up looks like a linear progress in which the country has been moving steadily toward further political and economic liberalization. Looked at up close, however, there has been a constant struggle between the leftists and the reformers, with the latter somehow prevailing over the former every time, perhaps fortuitously.104 When confronted with growing leftist aggression during the Hu era, some reformers seemed to believe that China’s progress along this path of reform was unstoppable and that any leftist obstacles would be overcome.105 But they were soon to be disillusioned by the revival of leftism in the Xi era. This time, the reformers didn’t win.

Episode 1: Scientific Development

The “Scientific Outlook on Development” is conventionally regarded as Hu’s signature party ideology. It was commonly regarded as a leftist critique that the market-oriented approach to development had caused worsening socio-economic inequality. However, the actual ideological battle that was being fought was far more intense than is known: It centered on how to define the phrase “human-centeredness” (以人为本),106 officially dubbed the “core” of the Scientific Development.107

On the issue of whether the Scientific Development was to be centered on “human” (人) or “people” (民), the initial closed-door discussion foreshadowed future acrimonious disputes. At the drafting meeting, a leading reformist establishment scholar, Gao Shangquan (高尚全), voted for using the term “people-centeredness.” His reason was technical: It is always the word “people” that appears in contemporary talk of popular sovereignty. However, with prescience, a reform-minded official, Zheng Bijian (郑必坚), warned that “people” was susceptible to being hijacked by the class struggle logic. He pointed out that “people-centeredness” had “content with political implications” (带有政治的内容) because some people might be arbitrarily excluded from the “people” (有些不是 “民”).108 Accordingly, the later debate among party theoreticians centered on the issue of whether “human-centeredness” could be equated with “people-centeredness.”109

By using the term “human-centeredness,” China’s reformers were emphasizing the value of human rights, the protection and promotion of individual interests, and political equality.110 This tapped into the Marxist concept of “human’s comprehensive development” (人的全面发展).111 An implicit message in choosing “human” was that the class struggle logic, which divides society into unequal groups, pitting one against the other for the sake of an abstract collective interest, was actually un-Marxist and should be discarded. Echoing Jiang’s call for inviting capitalists to join the Chinese Communist Party, one reformist voice remarked that “the ‘human’ of the ‘human-centeredness’ refers to all those who contribute to the cause of developing Socialism with Chinese Characteristics.”112 These reformist elements were all captured by Wen Jiabao’s definition, in which he mentions the “multi-dimensional needs” of humans, “respecting and protecting human rights,” and “creating a social environment in which there are equal [opportunities for] development and people can live up to their potentials.”113

Although “human” was adopted as the official term, the leftists tried hard to fight against this fait accompli by arguing that “human” referred to “people.” Behind the leftist conceptualization of “human-centeredness” was an essentially anti-Western and anti-capitalism worldview. The conservatives argued that any talk of “human” must be distinguished from similar, but qualitatively different, Western ideas such as “humanism” (人本主义) and “humanitarianism” (人道主义).114 The term was also not to be confused with “self-interest-centric” (个人利益至上) and “individual-centered” (以个人为本). Therefore, “mass-centered” (以人民群众为本) or “people-centered” (以人民为本) were more accurate terms.115 Using the language of Marxist historical materialism against the reformist talk of “universal values,” conservative party theoreticians often emphasized in the Marxism Project publications that “human” referred only to “concrete rather than abstract ‘human’ (不是抽象,而是具体的人).”116 Taken together, these charges all pointed to the political logic of class-based antagonism. For instance, “human-centeredness” was by nature Marxist and socialist,117 while everything was “capital-centered” under capitalism.118 “Human’s comprehensive development” was impossible under capitalism,119 because it must be preceded by the liberation of the proletariats.120 Relating the ideological dispute to policy, the conservative faction stressed that the ultimate realization of “human-centeredness” in every aspect of the human life is only possible with an economic system based on public ownership, since private ownership has no place in a socialist society.121

There was a conscious effort from above to stop this dispute. A reform-minded party theoretician, Xing Bensi (邢贲思), asked both sides to refrain from playing word games and reading too much into the differences between “human” and “people.”122 Then came an authoritative response from the Propaganda Department,123 which formulated a new definition of “human-centeredness.”124 This definition tempered both the leftist and reformist views and reduced the term to an abstract slogan of “serving the people.” It was a compromise that would soon break down. The disagreement over human-centeredness made a comeback immediately after the 17th Party Congress.125

To understand this dispute over human-centeredness it’s important to understand the broader purpose of the Scientific Development: It was a leftist attempt to subvert Jiang’s reformist party line. Given that Jiang’s Three Represents had recently been consecrated as the party’s new guiding ideology, it was highly unusual for Hu to rush to put forward his own ideology. Leftist aggression was evident. But the conservative faction never seemed to have full control in defining the concept. For instance, there was a failed attempt to make the Scientific Development immediately sacrosanct. A symbolic statement claimed that, with the Scientific Development, “the fundamental theoretical question of ‘what is socialism, and how to build socialism’ has been deepened and become one of ‘what is socialist market economy, and how to develop socialism under socialist market economy’” (什么是社会主义市场经济, 怎么在市场经济条件下搞社会主义).126

But this effort to foreground socialism ultimately failed. In the official version, the Scientific Development answers the question: “What kind of development shall be realized, and how to do it?” (实现什么样的发展、怎样发展).127 The framing was de-politicized by the reformers. Likewise, there were other leftist “wrong views” about the Scientific Development that the reformers took pains to combat. For example, the conservatives pitted the Scientific Development against (对立起来) Deng’s and Jiang’s party lines. The concept was thus meant as a corrective to the “wrong outlooks on development in the past” (过去错误的发展观).128 The reformist view stressed that Hu’s theory grew out of Jiang’s.129

Chinese politics in Hu’s early years in power were anything but a banal continuation of the reformist effort to lead China into a new stage of economic and even political liberalization.In short, the Scientific Development concept was not just a simple policy readjustment, which is conventionally attributable to Hu’s personal policy preference to prioritize social equity and redistribution over GDP growth. It was put forward as a political weapon. Indeed, signs of this left-right tension and the conservative challenge to the political status quo were visible during Hu’s early days in power. The most widely known sign was Hu’s re-interpretation of Jiang’s theory in a speech,130 in which the priority of the Three Represents was unambiguously shifted to the last “represent,” i.e., the people, or “the fundamental interests of the overwhelming majority of the people of China.”131 Jiang’s original framing was meant to highlight the other two “represents” — that the party should represent “the development trends of advanced productive forces” and “the orientations of an advanced culture.” It was no accident that Hu did this on July 1, 2003. Hu’s speech was referred to as the new “July 1st speech” (七一讲话).132 This was an attempt to override Jiang’s “July 1st speech,” delivered one year earlier, in which he officially introduced the Three Represents. In addition, it was unusual for a Chinese Communist Party leader to propose something new concerning party lines at a symposium.133 Moreover, Hu made an awkward digression on cadre discipline and the Mass Line spirit at the party’s 3rd Plenum held in 2003, which was dedicated to economic planning. There, Hu underlined his “Three For-the-Peoples” (三个 “为民”) slogan134 — an act of subversion targeting Jiang’s Three Represents.135 From 2004 through 2006, the Qiu Shi article series unleashed a rhetorical blitz intended to promote Hu’s leftist reinterpretation of Jiang’s theory.136

Even less known, but of no less political significance, is the hidden message in Hu’s speech delivered at Xibaipo (西柏坡) in late 2002. The well-publicized part of the story is that Hu cited Mao’s “Two Musts” (两个务必) to admonish party cadres to work hard for the people.137 However, what is missing in this common understanding is an important nuance: that Hu exclusively focused on the attitudinal aspect of “working hard,” — cadres’ faith in socialism, sense of mission, and altruistic style of serving the people — and mentioned nothing about the technocratic aspect. In fact, in the same text where Mao raised the idea of the “Two Musts,” he also talked about improving the party’s governing capabilities in technocratic terms.138 The lost message was supposed to have been delivered by Hu himself. However, because it wasn’t, it had to be delivered in an official booklet dedicated to elaborating on Hu’s Scientific Development concept in a reformist language,139 and more formally in Zeng Qinghong’s official speeches.140 Later, the contention over whether a technocratic or revolutionary spirit is the key driver of development was the backdrop to the major “party building” campaigns launched in Hu’s early years that were dedicated to enhancing the party’s “governing capacity” (执政能力) and maintaining its “advanced nature” (先进性).

Conservative push-back did not only take place privately among elites. Leftists also succeeded in attracting public attention and stirring up public anger. Soon after the Chinese Academy of Social Science completed its assigned research on “neoliberalism” (新自由主义),141 the anti-reform voices that first surfaced within the elite circles were soon amplified and brought into the public space. There was a high-profile public debate on China’s state-owned enterprise reform and the status of public ownership between 2004 and 2006.142 The leftist assertion that only the socialist way of economic production can lead to social justice found many supporters and sympathizers in Chinese society at the time. Shortly afterwards, the initial leftist criticism targeting specific economic policies went through further politicization — the problem was no longer about bad policies but the wrong model of development. This was later known as the “reflecting upon the reform” (反思改革) dispute or “the third debate on the reform” (第三次改革争论).143

Chinese politics in Hu’s early years in power were anything but a banal continuation of the reformist effort to lead China into a new stage of economic and even political liberalization. Beneath a seemingly festive political mood at the time, which was unmistakably marked by the widely acclaimed peaceful transition of power from Jiang to Hu, fierce political struggles were taking place.

Episode 2: Harmonious Society

The “Harmonious Society” (和谐社会) is conventionally regarded as Hu’s second major ideological contribution. It was a positive vision for China, which at that time was plagued by negative socio-economic conditions, like inequality and social instability. It was commonly believed to be a follow up to the Scientific Development and to be going against the reformist approach to development: the so-called “elitist” pursuit of GDP growth through market-oriented reform at the cost of the welfare of those who were economically lagging behind. This section offers a revisionist view: The Harmonious Society was, in fact, initially a reformist response to conservative challenges. Jiang’s Three Represents was repackaged with a new face of social harmony. The goal was to assure conservatives that further economic and political development in a reformist direction would not be fundamentally antithetical to the socialist ideal of social equity, and that the leftist concern over the negative impact of the market economy had been duly noted by the reformers At the same time, the Harmonious Society was also meant to be a stern warning to the leftists that the class struggle mindset be abandoned. But this “harmonious” repackaging of Jiang’s reformist blueprint met with strong resistance and was thwarted. The left-right battle centered on the political “positioning” of this newly proposed party line: Was it to be an ideological vision or merely a technical agenda for improving China’s governance at a time of growing socioeconomic tension?

According to the reformist conception, the Harmonious Society had multiple purposes. As China’s then-Vice President Zeng Qinghong put it, it was simultaneously “an ideal for governance” (治国理想), “a methodology of governance” (治国方略, 治国机制) and “a goal of governance” (治国结果).144

In this reformist view, as the highest communist ideal, the Harmonious Society was equated with the perfect world that Marx and Engels envisioned in their theoretical blueprint.145 It was “a harmonious social model based on the ‘free association of producers’” (自由人联合体).146 It was no coincidence that this statement strongly resonated with the reformist conception of human-centeredness. By emphasizing the “harmonious” nature of the ideal Marxist society, the reformist goal was to steer away from the revolutionary conception of socialism that highlights class struggle.

The Harmonious Society seeks a harmonious way to deal with socioeconomic problems. To deter radical egalitarianism, Zeng employed the classic reformist rhetoric by referring to the “primary stage” of socialism, a term that was coined to pacify conservatives by reassuring them that the goal of socialism had not been abandoned, on the one hand, and to justify the adoption of capitalism on the ground that it was necessary at the “primary stage,” on the other. “As a goal,” the Harmonious Society was the contemporary equivalent to “the communist ideal proposed by the founders of scientific socialism,” but “as a process,” it was “concrete, historical, multi-stage and multi-level, which cannot be achieved in one fell swoop.”147 Zeng also stressed that further economic development — not redistribution — was the key to reducing inequality. Additionally, Zeng underscored the importance of increasing the size of China’s middle class,148 a concept that is opposed to the binary logic of class struggle.