From Tajikistan to Moscow and Iran: Mapping the Local and Transnational Threat of Islamic State Khorasan

Islamic State Khorasan (ISK) emerged in 2015 as an official affiliate of the Islamic State in the Afghanistan-Pakistan region, rapidly interweaving its jihad into the web of local conflicts and grievances. Alongside drawing its initial recruits from disaffected members of the Pakistani and Afghan Taliban, as well as former al-Qa`ida Members, ISK bolstered its ranks by forging strategic alliances with local groups, leveraging their skills, knowledge, and well-established operational and logistical networks.1 Though ISK’s goals closely align with those of its parent organization, the Islamic State, its operational focus was primarily on the historical Khorasan region, which encompasses parts of modern-day South and Central Asia.2 Within its outreach and propaganda campaigns, ISK exploits regional conflict dynamics and militant infrastructures3 by fusing local grievances with its global agenda, propagating its message through local languages.4 This has enabled ISK’s to recruit broadly while serving as a central node for many like-minded militant factions. The recent terrorist attack in Moscow, claimed by the Islamic State and attributed by many to ISK,a drew global attention as it demonstrated ISK’s reach, ambition, and growing influence.5 And while evidence points to ISK’s involvement, including the recent Russia’s Federal’naya Sluzhba Bezopasnosti (FSB) chief Alexander Bortnikov’s claim that the attack was directed by ISK militants,6 much remains unknown about the specific organizational dynamics behind the execution of the attack, and Islamic State-central’s role in enabling it.

However, ISK’s behavior, at least since 2020, has indicated its intentions to carry out such transnational attacks,7 and arguably, may be viewed as the organization meeting the necessary structural thresholds to sustain a foreign operations campaign.b The Islamic State’s recent attacks in Iran—the January 2024 attack in Kerman, Iran, but also earlier strikes in October 2022 and in August 20238—also support this view.

Targeting Russia and Iran has long been a part of the Islamic State and ISK’s narratives around state adversaries. Russia has been portrayed as an oppressor of Muslims both historically and recently, with its military engagement in Syria as well as its history of hostilities in Afghanistan and the Caucasus.9 Iran has been depicted as an aggressor against Sunni Muslims, and of course, a symbol of Shi`a authority. With respect to Iran, the Islamic State conducted its first ever attack on Iranian territory on June 7, 2017, targeting the Majles-e Shor aye Eslami, Iran’s Parliament, and the mausoleum of Ayatollah Rohollah Khomeini, resulting in a death toll of at least 17 people and 50 wounded.10 In a video released a day later by Amaq News, a statement from a militant speaking Kurdish implied that the attacks were just the beginning of a prolonged campaign, declaring, “This message comes from the soldiers of the Islamic State in Iran, the first brigade of the Islamic State in Iran, which, God willing, will not be the last.”11 And indeed, the Islamic State attack in Iran was not the last. The brazen attack in Moscow along with the attacks in Iran and other foreign plots12 mark a pivotal moment in ISK’s evolution, not only showcasing its ability to strike at the heart of major regional and global powers, but also marking its progression into a different stage of the Islamic State’s insurgency model.13

The attack in Moscow has further heightened concerns among U.S. officials about the threat of similar terrorist attacks in the West, whether inspired or coordinated, as FBI Director Christopher A. Wray noted in April 2024: “Our most immediate concern has been that individuals or small groups will draw twisted inspiration from the events in the Middle East to carry out attacks here at home. But now increasingly concerning is the potential for a coordinated attack here in the homeland, akin to the ISIS-K attack we saw at the Russia Concert Hall a couple weeks ago.”14 Such concerns are neither new nor unfounded. United States Central Command (USCENTCOM) Commander General Michael Kurilla indicated in March 2023 that ISK’s ultimate goal could include striking the U.S. homeland, although attacks in Europe were more probable.15 Recently, in addition to a number of ISK-affiliated arrests in Turkey,16 in April 2024, Germany charged seven ISK-affiliated individuals, including five Tajiks, for planning attacks in the country and elsewhere in Europe.17 Among other factors, the involvement of Tajik nationals in external attacks has renewed questions and concerns about a series of issues: the presence and interconnectedness of Islamic State’s regional cells; ISK’s role in coordinating or supporting transnational attacks; the ability of ISK to strategically disseminate its propaganda and conspiracy theory campaigns to mobilize sympathizers from near and afar;18 and finally, the consequences of the dispersion of ISK’s battle-hardened militants, driven in part by the Taliban’s counter-offensives against the group.19

In this article, the authors explore various environmental and organizational factors underpinning ISK’s evolving operational behavior between 2020-2024, its growing regional influence and evolving military strategy, as well as the role of Central Asians—in particular Tajik nationals—in implementing ISK’s external operations that ultimately showcases ISK’s success in diversifying its human capital. First, the authors provide an overview of ISK’s strategy and operations in its traditional strongholds in Afghanistan and North-West Pakistan and discuss the impact of the Taliban’s counter-offensives against the group. The article then focuses on ISK’s strategic adaptation, discussing how the group continues to exploit various factors to its advantage. These factors include the broader permissive environment in which it operates, the Taliban’s diplomatic outreach efforts, and the potential security gaps resulting from rising tensions between the Taliban regime and Pakistan over the Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan. The authors also discuss the current ISK leader’s military doctrine to navigate the present environment. The article then in turn focuses on the organization’s effectiveness in appealing to and mobilizing a Central Asian audience, and the emerging role of its Tajik contingency in conducting external operations. The authors conclude with a discussion of the global implications of ISK’s evolution and key challenges to overcome in order to tackle the ISK threat effectively.

Traditional Strongholds: A Reduced but Sustained Violent Campaign in Afghanistan and Pakistan

Overview of Attacks

The suicide bombing at Kabul Airport in August 2021 not only sent shockwaves around the world but also marked a significant resurgence in ISK’s activities, a trend that persisted into 2022. (See Figure 1.) Under the leadership of Sanaullah Ghafari, also known as Shahab al-Muhajir, ISK aimed to regroup its dispersed forces, expand recruitment and propaganda efforts, and recover from its territorial losses.20 Following the collapse of Tamkeen in 2020 (the phase in which the Islamic State consolidates and secures its territorial control per the Islamic State insurgency model),21 ISK shifted its strategy to urban warfare, resulting in 83 (2020), 353 (2021), and 217 (2022) attacks in Afghanistan, and in Pakistan’s Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) province. Among other efforts,22 al-Muhajir focused on leveraging ‘strategic diversity’23—an intentional approach focused on diversifying the group’s personnel composition while internationalizing its agenda and operations.24 As ISK rolled out multilingual propaganda, it aggressively promoted its diverse militant base to broaden its recruitment reach and to take advantage of an arguably more permissive operational environment within Afghanistan marked by an absence of an internationally supported counterterrorism effort and inadequate governance structures under the Taliban regime. As ISK flows through the Islamic State’s method of insurgency,25 it is in this environment that the group has opted to leverage external operations as a means of extending its sphere of influence.26 Meanwhile, the Taliban regime and its establishment of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan (IEA) post-U.S. withdrawal has faced international pressure and embarrassment due to its inability to curtail ISK’s operations effectively.

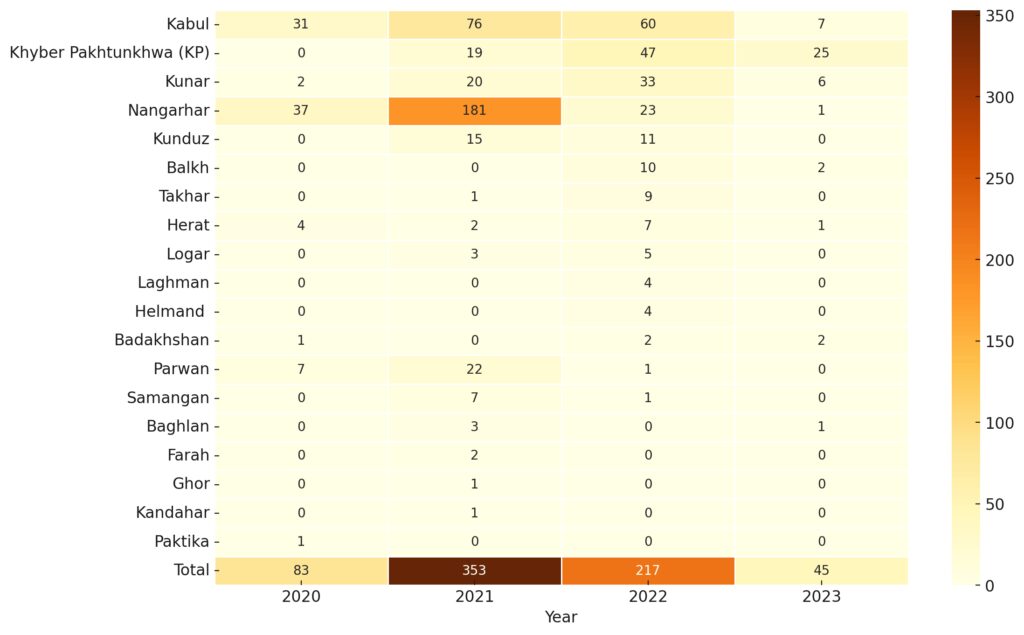

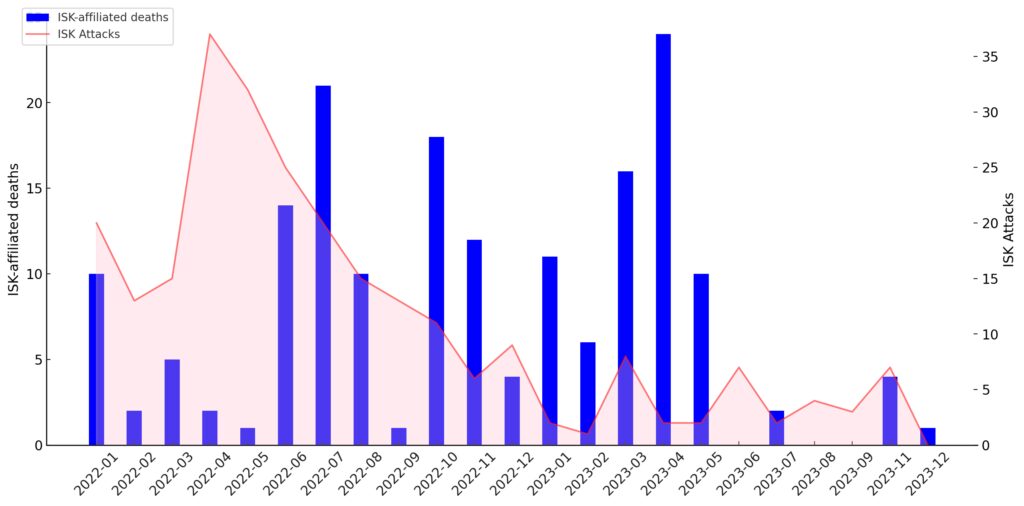

Providing an overview of ISK’s operations in its traditional strongholds of Afghanistan, and KP, Pakistan, Figure 1 shows ISK operations between the years 2020-2023 (ISK-claimed attacks),27 and Figure 2 provides an overview of Islamic State-affiliated fatalities in the Taliban’s counter-ISK operations across provinces between 2022-2024.28 Figure 3 plots the trends in ISK’s monthly attacks over 2022 and 2023 against its losses in clashes with Taliban security forces. As shown in Figure 1, ISK’s attacks within Afghanistan and KP peaked in the year 2021 at 353 attacks, before falling to 217 in 2022 and 45 in 2023. According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data (ACLED), as shown in Figure 2, the IEA’s General Directorate of Intelligence and Special Forces conducted a total of 75 operations targeting ISK throughout 2022 and 2023. These operations resulted in about 174 fatalities, (these reportedly include 163 ISK militant losses), with the highest numbers of fatalities occurring in Kabul, Nangarhar, and Kunar in 2022, and in Kabul, Herat, and Nimruz in 2023. Figure 3 suggests that as the Taliban ramped up targeting of ISK personnel around June 2022, sustaining them until April 2023, ISK’s attacks within Afghanistan declined consistently.

ISK initiated the year 2023 with a series of suicide attacks, executing five major attacks targeting Kabul’s military airport, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Kabul (twice), senior commander Daud Muzamil, and the Shi`a community in northern Balkh province.29 But the onslaught was halted by the Taliban’s crackdown against ISK leaders and idealogues, such as the killing of Qari Fateh Kawtar, Abu Saad Muhammad Khorasani, and Qais Laghmani,30 with other arrests claimed in Badakhshan in September 2023.31 Previous research has shown that historically, targeting ISK’s mid-tier leadership can constrain the group’s violence in the short term,32 while reinforcing perceptions of strength of the targeting entity;33 and indeed, the Taliban have seemed eager to promote this narrative, often rejecting international assessments of the ISK threat.34 In 2023, ISK attacks fell to a record low of 45 attacks—the lowest level in Afghanistan since ISK’s inception—with the most significant falls in Nangarhar and Parwan provinces (see Figure 1), and with over half its 2023 attacks taking place in KP, Pakistan (25 out of 45).

Down But Not Out

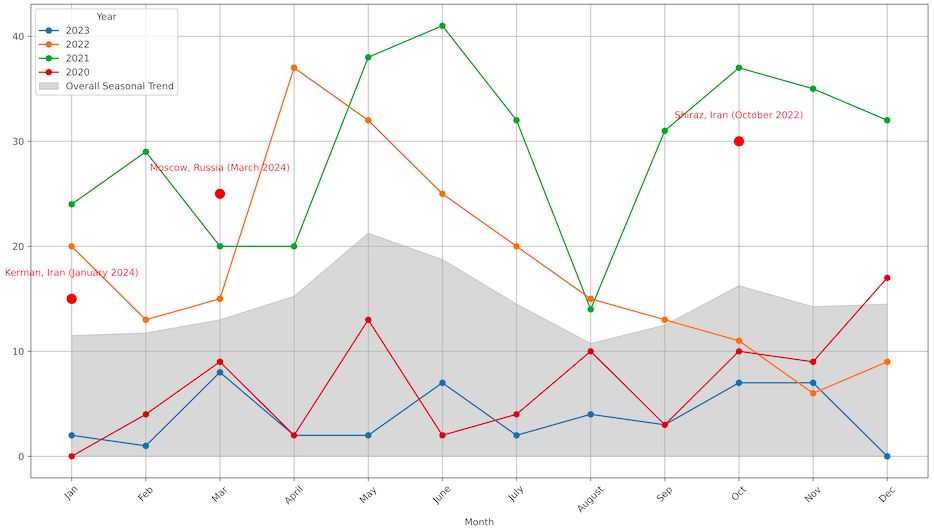

Despite the decline in its activity, ISK continued to strike against the Taliban intermittently, retaliating against key leaders and bringing into question the sustainability or long-term effects of the Taliban’s counter-ISK operations. In March 2024, CENTCOM Commander General Kurilla clearly noted his skepticism about the Taliban’s ability to dismantle ISK networks, stating, “The Taliban targeted some key ISIS-Khorasan (ISIS-K) leaders in 2023, but it has shown neither the capability nor the intent to sustain adequate counterterrorism pressure. In fact, this lack of sustained pressure allowed ISIS-K to regenerate and harden their networks, creating multiple redundant nodes that direct, enable, and inspire attacks.”35 In June 2023, after a brief hiatus, ISK carried out two consecutive major attacks within 48 hours in Badakhshan province, bordering Tajikistan, which resulted in the deaths of an acting provincial governor and a senior commander in separate incidents involving IED and suicide attacks, respectively.36 And then, within a span of three weeks during October and November, ISK struck at Afghanistan’s Shia communities through a suicide attack on Imam Zaman Mosque, the largest Shia mosque in Baghlan province’s capital city; Pul-i-Khumri in October;37 and two attacks in Kabul the following month.38 ISK continued its sectarian attacks into 2024, conducting an attack in January in Kabul’s Hazara Dasht-e-Barchi neighborhood,39 and a mosque bombing in Herat in May 2024.40 Across the border in Pakistan, ISK was also linked to targeted killings of government officials such as a deadly suicide attack on Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam-Fazl (JUI-F) in July 2023,41 and another suicide attack in Baluchistan in September 2023, that was suspected to be linked to ISK.42 A series of other unclaimed attacks in Pakistan, bearing the hallmarks of ISK’s tactical preferences, have continued to raise concerns about the group’s threat in the country.43 In Figure 4, the authors show the seasonal trends in ISK’s attack tempo; across the four years (2020-2024), ISK’s attacks generally seemed to peak between April and August. Within this context, it is interesting to note that attacks attributed to ISK in Russia and Iran generally fall outside of its busy season, suggesting that its external operations may be a complement rather than a substitute of more locally based operations—designed to expand its influence—while intentionally laying low in Afghanistan in the face of Taliban pressure. As Aaron Zelin noted in September 2023, ISK appeared to be weaker in Afghanistan during the second year of the Taliban’s rule, “while paradoxically expanding its external operations capacity.”44

ISK’s Evolving Environment and Strategic Adaptations

Exploiting Environmental Factors

Despite the Taliban’s success in reducing ISK attacks in Afghanistan to historically low levels, this does not necessarily represent a permanent degradation of the group,45 given the group’s demonstrated resiliency and tendency to adapt to changing environments. While the Taliban publicly downplay the ISK threat, the counter-messaging campaign launched by the Taliban’s Al-Mirsad media in mid-2022 suggests otherwise.46 At the very least, the Taliban’s extensive campaign against ISK unmistakably signals their recognition of the group’s persistence. Three key environmental factors, in addition to ISK’s leadership, benefit ISK’s operational survival in the region, as discussed below.

First, ISK finds itself in arguably the most permissive environment since its formation, given the absence of any international troops or a unified inter-state counterterrorism response, and lack of an externally supported government in Afghanistan.c Despite the Taliban’s increased offensives targeting ISK, the group’s adaptability and the Taliban’s multifaceted challenges in governing the country and managing competing priorities with limited resources create a complex security landscape that ISK can navigate to exploit vulnerabilities and continue its activities, even if with some disruptions. ISK continues to position itself as an umbrella organization, as a partner of choice for other weakened militant factions in the region previously aligned with the Taliban insurgency, and as a formidable resistance platform for regional aggrieved populations facing political and socio-economic issues, compounded by ineffectual and corrupt governments. This ties into ISK’s growing appeal amongst Central Asians, as discussed in the next section.

Second, within this larger environment and an internationally isolated Taliban regime, ISK has skillfully exploited the Taliban’s efforts to normalize relations with regional state actors, such as Iran, China, and Russia.47 These efforts, while crucial for the Taliban’s long-term survival and international recognition, have sometimes conflicted with the group’s insurgency-era narratives and ideological principles. ISK has seized upon these apparent contradictions, using it as a powerful propaganda tool to highlight the Taliban’s deviance from ideological purity and appeal to disaffected Taliban fighters.48 For example, ISK’s key criticisms in this regard include the Taliban’s failure to enforce the same level of sharia punishments as they did during their previous rule in the 1990s, their efforts to strengthen diplomatic ties with non-Muslim countries, their tolerance of non-Muslims and international organizations operating within Afghanistan, and their reluctance to take action against countries like China, which ISK accuses of committing atrocities against Muslims.49 In its strategic messaging, ISK portrays the Taliban as abandoning their religious objectives in exchange for political power.

Third, strained relations between the Taliban and Pakistan over the Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) have created new opportunities for ISK for cross-border activities, as the IEA and Pakistan hurl accusations at each other of sponsoring militancy. The Taliban regime counters Pakistan’s accusations about the TTP using Afghan soil to attack Pakistan50 with the claim that ISK militants are using Pakistani territory to launch attacks in Afghanistan.51 In a recent video released in May 2024 by the Taliban’s Al-Mirsad media, individuals purportedly affiliated with the Islamic State note the involvement of Pakistani intelligence agencies in recruitment for the group.52 While the veracity of such claims is uncertain, it is worth noting that Afghan salafi communities in Pakistan have contributed to ISK’s formation in 2014. This links back to the historical presence of salafi communities in Kunar, Afghanistan, and Bajaur, Pakistan, in the 1980s,53 with many who joined ISK in 2014 hailing from Bajaur, such as now deceased ISK emirs Abu Saeed Muhajir and Abu Umar Khorasani, and senior religious leaders Sheikh Jalaluddin and his brother Abu Saad Muhammad Khorasani.54 At present, ISK is believed to have isolated cells in the Bajaur area, with young recruits who are relatives of deceased ISK members and harbor revengeful motivations against Taliban members.55 Relatedly, Pakistan’s policy post-Kabul takeover—offering anti-state militants in Afghanistan an opportunity to reintegrate peacefully56 within Pakistan—has led the Taliban to claim that this enabled ISK members to escape Taliban reprisals and remain operational from across the border.57

Al-Muhajir’s Strategy to Adapt and Rebuild

Notwithstanding the Taliban’s targeted campaign in Afghanistan, ISK has sought to reposition itself vis-à-vis the changing dynamics in the region, as evidenced by its targeting choices. Much of this revised strategy has been developed under the auspices of its current leader, al-Muhajir, who has written at least three books on ISK’s strategy, providing relevant insights.

One of these books, entitled “Management and Leadership System” (2021), discusses management of an Islamic State province, with topics ranging from organizational design to suggestions for specific security measures against detection and operations, such as avoiding in-person meetings. In 2021, al-Muhajir, emphasized secrecy and hiding as key tactics in ISK’s current “phase of guerrilla warfare,”58 encouraging hit-and-run tactics while territorial control is deemed to be too costly.59 Here, he appears to subscribe to the Islamic State’s guidance for guerrilla warfare, with the main objective of inflicting harm upon the enemy.60 More generally, he discusses three phases of guerrilla warfare. In the first phase, the group slowly rebuilds its military capabilities while conducting low-cost, high-impact attacks to keep the enemy engaged. In the second phase, militants can attempt to take control of limited remote areas at night, creating hideouts for group members. The third phase envisions a slow retreat of the enemy from roads and villages where ISK has entrenched itself with the ability to send reinforcements elsewhere. In a 2023 book, “Islamic Political System,” the ISK leader addresses a number of political and military issues.61 Al-Muhajir argues that to intimidate the enemy, ISK militants should strike deep into enemy territories, especially in major cities with high security, targeting anti-ISK religious and social figures, officials unpopular with local populations, and foreigners for publicity.

All these elements are directly linked to the Islamic State’s insurgency method,62 and can be observed to varying degrees in ISK’s post-August 2021 behavior on the ground, whereby ISK expanded its types of warfare and conducted attacks in major cities: Kabul, Mazar-e-Sharif, and Kandahar in Afghanistan and in Quetta, Mastung, and Peshawar in Pakistan.63 Alongside government officials and security forces, ISK attacked minorities, rival clerics, and foreigners.64 The attack carried out in Bamyan province on May 19, 2024—claimed by the group and which killed three Spanish tourists and an Afghan national as well as injuring several others—should be interpreted within the context of ISK’s strategy to target high-profile targets, aiming to spread fear, gain notoriety, and undermine the Taliban’s authority.65

As noted above, while ISK’s attacks decreased over time, they continue to exhibit complexity and sophistication in their planning. Pictures and descriptions released by Amaq indicate ISK’s careful planning in a series of attacks in 2022 such as the attack on Pakistan’s Charge’ d’Affaires in Kabul via a sniper attack,66 and on the Longan Hotel frequented by Chinese personnel, as well as in its assassination of the Taliban provincial police chief for Badakhshan.67 Similarly, in Pakistan, ISK’s long trail of assassinations against religious scholars affiliated with Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam-Fazl (JUI-F)—culminating in the July 2023 suicide attack in Khar—also required extensive monitoring by local networks.68 In a more recent attack in March 2024,69 ISK’s second-ever attack in Kandahar, the group conducted a suicide attack outside the Kabul Bank, with pictures in Al Naba depicting ISK’s advanced planning, which included tracking the work shifts of bank personnel and other activities.70 Two months later, on May 20, this attack was followed by a third attack in the Taliban’s spiritual capital, Kandahar, targeting police forces and highlighting ISK’s willingness to challenge the Taliban in their strongholds, as per al-Muhajir’s strategy.71

ISK’s Propaganda and Recruitment Strategy: Sourcing from Central Asia

ISK has also embraced the centrality of establishing a propaganda campaign to create competing ideological narratives, identities, and engagement as part of its adoption of the Islamic State’s insurgency model.72 In late 2021, ISK’s renewed propaganda campaigns focused on Central Asia became notable. ISK publications in Pashto and Farsi languages started to be translated into Tajik and Uzbek languages by Al-Azaim Foundation’s linked channels, while original books on religious and political topics were published by Al-Azaim Foundation in Tajik and Uzbek languages.73 Soon after, pro-ISK Tajik media channels swelled in numbers on Telegram and on other platforms, prior to which, Tajik users mostly relied on the Farsi version of ISK Pashto radio, Khorasan Ghag, named Sadoi Khorasan.d In mid-2021, the Tajik language (Cyrillic alphabet) Sadoi Khuroson channel was established on Telegram, releasing several original audios,74 and by 2022, numerous other pro-ISK Central Asian languages media entities popped up online, indicating a high degree of interconnectivity.75 The Uzbek branch also developed media entities, which ultimately were incorporated into the official ISK media arm, al-Azaim Foundation.76 Slowly, the Uzbek branch of al-Azaim merged into the Tajik one, which supports its publication, although it intermittently releases translations, infographics, and bulletins via the pro-Islamic State platform I’lam Foundation.e Alongside these efforts, in 2022, ISK’s centralized media outlet, al-Azaim Foundation, started to diversify the languages of its media products, including Tajik and Uzbek language translations of its Pashto and Dari releases as well as original pieces of propaganda directly appealing to Central Asian audiences. Significantly, the scripts for these products are in Cyrillic (Tajik) and Latin (Uzbek) as used within each respective country, signaling that the products were directed toward Uzbek and Tajik nationals rather than for Tajik/Uzbek-speaking communities in Afghanistan that use Arabic scripts.77

Localized Narratives

In its messaging, ISK positions itself as the sole platform for Central Asian jihadis to combat their home governments, often highlighting the 2015 defection of IMU members to ISK and the subsequent Taliban attacks on these defectors and their families.78 It tailors its messaging to criticize and threaten the governments of Tajikistan and Uzbekistan, accusing them of suppressing Islam and being subservient to Russia, China, and the United States. It criticizes Uzbekistan’s cordial relations with the Taliban, and has alleged that humanitarian aid and projects such as the Uzbekistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan transnational railway are plans to spread democracy in Afghanistan.79 In the Tajik version of Pashto language Khorasan Ghag magazine, Sadoi Khuroson magazine, officially launched by ISK a week after the 2024 Moscow attack, for example, there is ample criticism directed at Tajikistan’s president, Emomali Rahmon, specifically at his model of governance and subservience to Russia.80

The new magazine bears the same name of one of the most impactful media entities of Tajik ISK: Sadoi Khuroson Radio, the Tajik version of Pashto Khorasan Ghag Radio. So far, Sadoi Khuroson Radio has been prolific in its output. As of mid-May 2024, a total of 553 recorded episodes have been recorded since May 10, 2021; while some of the recordings are nasheedsf and translations of Islamic State Central’s leader and spokesman, the majority feature different speakers who narrate their own stories and motivate others. On Sadoi Khuroson, ISK members talk in Tajik, Farsi, but also in Russian and, occasionally, in Uzbek.81

Topics and speakers in Central Asian languages are highly diversified. Audio statements by Sadoi Khuroson, shared on multiple affiliated channels,g include speeches by deceased ISK members, including those linked to attacks in Kabul and Peshawar, Abu Muhammad Tajiki, and Julaybib Kabuli, as well as the founders of the ISK Tajik media cell, such as Yusuf Tajiki.82 Tajik channels also regularly share the contents of prominent Tajik recruiters Abu Osama Noraki (Tajiddin Nazarov) and Abu Muhajir, tailored to lure Central Asian recruits into ISK folds.83 On a smaller scale, Xuroson Ovozi—the Uzbek version of Khorasan Ghag Radio—has also released audio episodes in the past,84 which published audio interviews with ISK members who made hijra (migration) from Movarounnahr (Central Asia) to Afghanistan. For example, two recent cases of Uzbek militants who traveled from Uzbekistan to Afghanistan to join ISK, as featured in a Xuroson Ovozi production from 2024, include “Jafar.”85 In his narrative, Jafar, depicted as an ISK militant, claims that he was originally a follower of Abdulloh Zufar, a radical Uzbek preacher allegedly based in Turkey who has been critical of Uzbek government but is cordial toward Turkey; however, Jafar claims to have distanced himself from Zufar and joined ISK due to its clear message.86 While all ISK members express anti-Afghan Taliban narratives, militants from Central Asia frequently discuss a sense of marginalization from their broader communities and cite religious motivations to join ISK.

Ideological Bridges with Zero Tolerance for Disagreement

An important connection between ISK’s Central Asian-focused propaganda and its Dari-Farsi channels is the relevance of salafi religious figures. ISK’s Central Asian channels widely share sermons of Sheikh Mustafa Darwishzadeh, Sheikh Obaidullah Mutawakkil, Ustad Abdul Zahir Da’i, and Sheikh Omar Salahuddin, inter alia, whose contents are also used by Dari/Farsi channels, creating an ideological bridge between countries and nationalities.87 However, as ISK exploits the religious reach of prominent scholars to reinforce its legitimacy among multiple ethno-linguistic constituencies across Central Asia, Afghanistan, and Pakistan, the group is equally fast in discrediting those same religious figures if they start to become critical of ISK. One of the most prominent scholars who served as a beacon of religious knowledge for ISK Central Asian members is Tajik national Sheikh Abu Muhammad Madani.h However, Madani was recently condemned by ISK (similar to what happened to influential Afghan salafi scholar in Peshawar Sheikh Aminullah Peshawari) due to growing ideological distance from ISK.i ISK declared takfirj on Madani after his claims that the Moscow attack was linked to Russian intelligence, and his criticism of targeting civilians.k ISK responded via two books in Farsi language—with Tajik language audio versions—criticizing Abu Muhammad.88 Given that Madani has thousands of followers online across multiple platforms and a sizable central Asian audience, ISK’s willingness to openly challenge him is indicative of the group’s willingness to discard scholars when they interfere with its propaganda efforts to recruit and mobilize potential supporters.

Hijrah or External Operations

Appealing to Central Asian militants thus appears to be a concerted approach pursued by ISK, as further demonstrated by the presence of associated promotional biographies throughout ISK media outputs. For example, the English language magazine, Voice of Khurasan, published by Al-Azaim Foundation, has featured biographies of two ISK commanders who defected from the IMU. One of these is Asadulloh Urganchiy, who became ISK’s media officer responsible for Uzbek language media production, and a prominent ideologue with widely shared sermons.89 The other, Abu Muhammad Uzbeki, served as a medical doctor in Afghanistan upon joining the group.90 Such narratives and biographical sketches serve as inspirational and recruitment tools targeting Central Asian sympathizers, with Pashto and other local language features targeting audiences in Afghanistan and Pakistan, and English language products providing access to Western audiences. To mobilize support, ISK encourages involvement in external attacks as well as travel to Afghanistan. For example, in a recently published book in Pashto language, ISK emphasized its goal of toppling Tajikistan’s government, urging Muslims in Tajikistan, especially scholars and youngsters, to join ISK’s efforts in Tajikistan or migrate to Afghanistan.91 The call to migrate to Afghanistan was also included in ISK’s 2024 Eid message, published in Tajik, Russian, and Uzbek languages.92 A series of accounts on Telegram appear to be tasked with providing the practical steps to potential recruits for settling in Afghanistan, where users express an interest to emigrate.93

ISK’s adoption of guerrilla warfare tactics, its media campaign, along with its calls for hijrah and encouragement of external attacks appear to be the cornerstones of its current rebuilding strategy, aligned with the Islamic State’s general approach to warfare. ISK’s appeals to Central Asians in particular underscores its envisioned pathway to expanding its influence and recruitment within and beyond Afghanistan’s borders. This approach aims to reinforce ISK’s numbers in its traditional strongholds in Afghanistan-Pakistan while simultaneously developing its transnational capacity, likely enhancing the group’s ability to pursue its objectives across the region.

The Tajik Contingent in ISK’s External Operations

Regional Targets

Within ISK’s Central Asian mobilization campaign, its Tajik contingent appears to have emerged as its leading unit involved in external operations with a history of Tajik Islamic State conducting attacks within Tajikistan. In July 2018, for example, Islamic State-affiliated Tajik militants attacked Western cyclists in Tajikistan’s Danghara District, killing four and wounding others, while in November 2019, 15 Tajik nationals affiliated with ISK were killed in a clash with Tajik security forces along the Tajik-Uzbek frontier, allegedly enroute to Afghanistan.94 In May 2019, a prison riot claimed by the Islamic State left three prison guards and 29 inmates dead in a prison east of Dushanbe.95 More recently, in December 2023, Kyrgyzstan security services claimed to have arrested two alleged ISK members planning a bombing in the city of Jalalabad, Kyrgyzstan, and in January 2024, the Interior Ministry of Tajikistan claimed that a bomb attack on the People’s Democratic Party of Tajikistan was carried out by individuals connected to an extremist group, with Radio Ovozi’s source in law enforcement agencies pointing specifically to ISK members.96

As depicted in the above examples, while Central Asian militants are involved in attacks within Afghanistan, ISK appears to call upon diaspora sympathizers overseas to support ISK’s agenda of orchestrating transnational attacks. Following the January 3, 2024, attack in Kerman, Iran, and the January 28 attack in Istanbul, Turkey, each government’s investigations concluded that the cells involved in the two attacks were linked to ISK’s extended network.97 According to authorities, the attackers in Iran had traveled to Turkey and Afghanistan, with one being a Tajik national and the other two with Tajikistan and Russian Northern Caucasus backgrounds. The existence of a broader Tajik network in Turkey with links to ISK in Afghanistan was also noted in a recent United Nations Security Council report, which claimed that Tajik individuals were fundraising and supporting logistics between Turkey, Afghanistan, and neighboring countries.98

Western Targets

Furthermore, ISK’s Tajik connections stretch to the West as well, particularly in Europe. Several plots have been foiled by European security agencies over the last few years involving Central Asian nationals, including a notable number of Tajiks among others. ISK aims at galvanizing Muslim communities in the West and providing guidance from afar by exploiting international developments and incidents to exacerbate antagonism between Western societies and their Muslims populations. For instance, in the wake of the episodes of desecrations of the Qur’an in Europe, ISK published books and videos on several occasions urging Muslims to avenge the offense.99 Consequently, individuals affiliated with ISK attempted to carry out retaliatory attacks; on March 19, 2024, Germany’s law enforcement revealed that two suspects had been arrested after being instructed to carry out an attack against the Swedish parliament in Stockholm by ISK.100 This plot, which reportedly had been directed by ISK, constituted the 21st external plot linked to ISK in 12 months.101

Other plots in the West provide further evidence of the involvement of Central Asians and ISK’s role in facilitating or inspiring these. In another case in Germany, in April 2024, seven individuals arrested the previous July and subsequently charged with plotting attacks in the country and in other European countries were also reportedly linked to ISK.102 In 2023, Tajik and Uzbek nationals were arrested in a series of operations in Austria and Germany in December, reportedly planning to conduct attacks on behalf of ISK during Christmas or New Year’s Eve in Vienna and Cologne.103 Prior to that, in 2020, four Tajik citizens being guided by Islamic State members in Afghanistan and Syria were arrested after plotting to attack U.S. Air Force bases in Germany.104 And after the Moscow attack, French President Emmanuel Macron revealed that his country’s intelligence services had thwarted multiple plots linked to ISK.105 Reportedly, French intelligence had increased its scrutiny of suspects of Central Asian origin including Turkmen, Kyrgyz, and Kazakh nationals.106

These examples underscore the urgent risk posed by ISK’s ability to inspire and remotely coordinate attacks and recruit individuals from disenfranchised communities across borders, highlighting the group’s strategic and tactical evolution. The strategy to target diaspora communities to incite attacks in the West—a tactic straight out of the Islamic State’s general playbook—became particularly evident after the 2024 Moscow attack carried out by a team of Tajik nationals affiliated with the Islamic State. Prior to the attack, there had been several warnings of a possible ISK plot in the country: On March 9, 2024, Kazakhstan’s National Security Committee reported that two Kazakh citizens had been killed by law enforcement in Russia’s Kaluga region, as Russian security forces stormed an ISK cell planning to attack a synagogue in Moscow; also in early March, the U.S. government shared information with Russia about a potential Islamic State attack in Moscow.107 The subsequent major attack in Moscow was thus the apex of years of ISK’s anti-Russia propaganda, which combines different elements of ISK’s ideology, from historical antagonism toward Russia to anti-Taliban narratives and Central Asian ambitions.108 Thus far, ISK’s Tajik contingent has emerged as a core force in the group’s external operations, with Tajik militants not only carrying out attacks locally and regionally but also serving as key actors for attacks in the West, as exemplified by the 2024 Moscow attack and other foiled attacks in Europe noted above.

Challenges to a Coherent International Response

ISK’s nearly decade-long presence in its traditional strongholds of Afghanistan and Pakistan, coupled with its expanding reach and appeal among Central Asian populations and its prioritization of inspiring and coordinating transnational attacks as part of its growth strategy, underscores the multifaceted and evolving nature of the threat posed by this resilient terrorist organization. Moreover, ISK’s involvement in attacks and plots targeting powerful countries such as Russia, Iran, and those in Europe serves to unite its diverse members behind a shared narrative of confronting prominent and common adversaries. Despite ISK’s recent decline in attacks in Afghanistan, the group retains the determination and capacity to conduct destabilizing high-profile attacks in multiple countries. The group remains resilient, but more worryingly, it has learned to adapt its strategy and tactics to fit evolving dynamics, and exploit local, regional, and global grievances and conflicts.

The implications of ISK’s increasingly regional influence and successful external operations are far-reaching and complex. On a regional level, ISK-linked attacks in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iran, Russia, and elsewhere showcase the group’s potential to destabilize the region further, exacerbate existing tensions, and provoke retaliatory measures from targeted countries. ISK attacks against U.S. allies and partners, especially those originating from Afghanistan, also have the potential to undermine U.S. influence and reputation given its peace deal with the Taliban.109 The group’s ability to recruit from and operate in different countries, with the heavy involvement of Central Asian nationals, highlights the transnational nature of the threat and heightens concerns for ISK’s potential to inspire or direct similar attacks in Western nations, as indicated by FBI Director Wray’s recent warning. This underscores the need for a comprehensive, coordinated, and strategic international response to address the evolving threat posed by ISK.

An effective response to ISK demands a unified regional approach based on shared intelligence, leadership targeting, and human-security measures. However, this necessitates overcoming several challenges to establish strong interstate partnerships. Firstly, the focus on great power competition and interstate rivalries at the expense of counterterrorism in the region can hinder a coherent and coordinated approach that ISK readily exploits within its propaganda campaigns.110 Secondly, “over-the-horizon” counterterrorism approaches that rely on airstrikes and special operations raids launched from outside the region require locating reliable partners in the region. Third, governments need to be more realistic about the Taliban’s ability to constrain ISK in the long-term, as any sustained gains will be contingent upon cooperation among regional partners to disrupt ISK’s operations, tracking its financing, and preventing future attacks. Finally, kinetic approaches that do not also address underlying conditions that allow groups like ISK to thrive should not be pursued in isolation or as long-term security strategies. Ultimately, the success of any international response to the ISK threat will depend on its ability to address the underlying socioeconomic and political grievances that fuel radicalization and violence, requiring a long-term commitment to engaging with local communities, and empowering civil society actors to build resilience at the grassroots level.